Off script

A zany antidote for alienated teens and Latin letters for the Turks. Plus some new photographs and a tariff-ic satire.

PERSONAL HISTORY

Stoner TV, circa 1970

WHEN YOU’RE SEVENTEEN and high on Kansas weed, you need something cooler than Bonanza to watch on TV. It’s not that I didn’t like Hoss or Little Joe or even Adam. Sometimes I’d randomly find myself humming the da-dena-dena-dena-da-da-da theme song. But I had watched Bonanza with the family when I was ten and now I was a lot more grown up and partaking of an illegal substance for chrissakes.

Playing the show with the sound off on the TV was campy-cool, though, as we passed joint after joint around our small circle of friends. Getting stoned on Kansas grass—“I think I’m high. Are you high yet?”—was like trying to get drunk on Kansas 3.2 beer. Piss beer. The ax-wielding, saloon smashing prohibitionist Carrie Nation got her start in Kansas, and serving real beer and mixed drinks was still against the law.1

We sat cross-legged on the worn-out carpet of the guy we bought our dope from, who was a little older and had his own house. Bonanza or Gunsmoke or some local show played on the screen but the soundtrack was the Rolling Stones and Grateful Dead and Neil Young. Saturday night was different. Around midnight, we turned off the stereo and cranked up the volume on the TV. Saturday night was the Uncanny Film Festival and Camp Meeting, broadcast at midnight from nearby Tulsa, Oklahoma.

THE SHOW WAS hosted by Dr. Mazeppa Pompozoidi with his sidekick Teddy Jack Eddy.2 Mazeppa often dressed as a velvet-cloaked wizard with a pointed cap. He aired Busby Berkeley musicals, Laurel and Hardy comedies, and daffy old horror movies such as Revolt of the Zombies and Attack of the 50-foot Woman, which he interrupted with zany skits. Mazeppa was, in other words, the perfect medicine for an alienated and stoned midwestern teenager trying not to think about the draft or a possibly pregnant girlfriend.

The skits were as breakneck as they were goofy. Mazeppa was played by Gailard Sartain, later of the hillbilly comedy Hee Haw. Gary Busey, who once described himself as a raccoon on speed, played Teddy Jack Eddy as a loud-mouthed redneck. With his over-the-top antics, Busey was always trying, Groucho-style, to force Sartain to break character. Another sidekick, Sherman Oaks, conducted interviews with made-up “famous” guests—one was Toenail Man—and the whole crew staged fake commercials long before Saturday Night Live did the same.

Our little group of hippies felt personally connected to Busey, who’d attended a local junior college before going on to acting fame in Hollywood. He also played drums for another of our heroes, Leon Russell, who made a genuinely famous guest appearance on the show.3 We’d fantasize about driving down to visit Leon in his studio in an old Tulsa church. Of course, it remained a fantasy. But that felt sense of connection was meaningful when everything important and worthwhile seemed to happen in the rest of the world. Beyond Mazeppa’s fun-making, which satirized and soared beyond our stifling small-town reality, the show threw us a lifeline when we were still too young to know how to escape.

–Kerry Tremain

A collection clips of Mazeppa’s Uncanny Film Festival is available on YouTube. Watching them now is painful. I guess you had to be young, stoned, and desperate to appreciate such goofiness.

In 1970, Kansas had a spiritual successor to Carrie Nation in the form of a Wichita sheriff named Vern Miller. He parlayed his head-busting of anti-war demonstrators into electoral success as the state attorney general. He then gained a national reputation by breaking into the homes of KU students in the middle of the night looking for drugs. Most of the charges never stuck, but we still feared him. One friend packed up and left town for a month when he heard that Vern had checked into a local motel. Statewide enthusiasm for his tactics waned when he tried to force Amtrak and the airlines to suspend the serving of alcohol while rolling through or flying over Kansas.

This memory of the Uncanny Film Festival was prompted by the recent passing of an outstanding illustrator that I worked with at Mother Jones (see below). As a young man, Brad Holland lived in Tulsa. Once, while discussing an assignment, we discovered our joint appreciation of Dr. Mazeppa Pompozoidi. His friend Steve Heller has written a lovely remembrance in Print magazine. Rest in Peace, Brad.

Mazeppa also had a band called the Natural Brass Company. On the jacket to their recording of “Scope Them Turkeys Out,” he lists himself as a “figment of your imagination.”

ON LANGUAGE

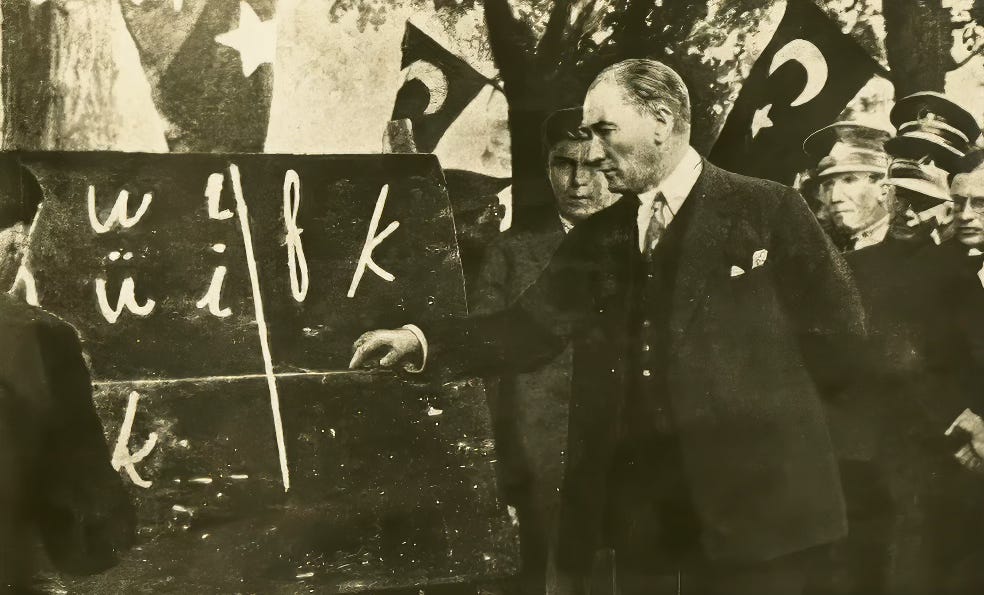

The Turkish revolution in writing

THE YEAR I TURNED TEN, a Turkish exchange student named Belkis came to live with my family. That same year, I was transformed from a child who could read to a child who had to read. Instead of fantasizing that I lived in the turret of a castle with my pet dragon, I re-imagined the turret as a library whose door I could slam shut behind me. The written word became my most faithful playmate.

Sometimes I watched Belkis as she dutifully wrote home every week in a beautiful script with large looping letters. Though she appeared to use the same letters that I did, I was unable to read a single word. Knowing that Turkish was a different language than English, I must have believed it had a suitably foreign-looking alphabet. But it didn’t.

When I asked, Belkis told me how the Turkish script was created. She was proud of all things Turkish, especially those having to do with Kamal Ataturk, the founding father of modern Turkey. I’m sure she told me the story in some detail, but over time it leaked out of my brain, leaving only the vaguest of traces. Recently, I re-learned this history and was struck anew by how shockingly revolutionary it was.

The first writing system of the Turkic-speaking peoples of Central Asia is called the Orkhon alphabet. Little remains of it. Orkhon was engraved onto just a few monuments from the 8th century—essentially, they said, “Mr. Big Was Here”—and there’s no evidence of widespread literacy.

By the 10th century, most Turkic-speakers had adopted Islam and began using Arabic script to represent Turkish speech. Though the alphabet wasn’t a good fit with the sounds of Turkic languages, Arabic was the language of God. No one was keen to alter it to accommodate Turkish phonology. The script also formed a readymade bridge to a religion and culture in which the Turks were becoming fluent.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, the Ottoman Turks took full control of the Anatolian peninsula. They adopted many handy words from Arabic and Persian, and the Arabic writing system became the official script of their empire. Ottoman laws, decrees, poems, diplomatic messages, and songs were written with it. Over time, like an expensive suit that doesn’t quite fit, the Turks managed to make it work. After all, the fabric was so gorgeous!

But even fine fabric can fray. By the beginning of the 20th century, various European empires had chipped away at the Ottoman empire. The Turk’s disastrous decision to back the Germans in WWI resulted in a post-war occupation by Allied forces in 1918. The following year, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk launched a war of independence against both the occupiers and the Ottoman sultan, and four years later he founded the Republic of Turkey. By the time he died in 1938, he had engineered a wholesale reformation of politics, law, culture, economy, education, and religion throughout Turkey.

ATATURK MADE A SPECIAL project of language reform. He considered the Ottoman variant of the Turkish language to be a tool of an autocratic elite and its written version an archaic obstacle to improving literacy in the country. At independence, only ten percent of the people could read. The script contained many letters representing sounds not found in the Turkish language and lacked letters for many common Turkish sounds (including most vowels), making written Turkish cumbersome to learn. Imagine trying to write the word “alphabet” in an English script that contained no “a” or “b.”

Attaturk instead turned to the Latin alphabet, one he considered to be allied with the scientific, rationalist views of the West. Though still wary of Western powers, his greater fear was undue Arab and Islamic influence. Attaturk embraced Enlightenment ideals that celebrated the human capacity for progress. He advocated the separation of church and state and the emancipation of women, while promoting the Turks as an ancient, proud, and independent civilization.

In July 1928, Ataturk appointed a nine-person commission of linguists, educators, and political reformers to create the new alphabet. Drawing on versions of Latinized Turkish developed earlier in the century, the commission rapidly finalized a new script and developed a five-year plan for its implementation. Ataturk accepted his commission’s recommendations with one exception. He changed the implementation plan from five years to three months.

Taking the role of educator-in-chief, he then travelled the country to promote the new writing system. Three months later, as directed, the alphabet was passed into law. Starting that December, newspapers, magazines, subtitles in movies, advertisements and signs had to be written with the new alphabet. By January all public communications and books were required to use it. The civil population was allowed just another six more months to use the old alphabet in transactions with public institutions.

Although Belkis would never believe it, Ataturk did have serious flaws. While he didn’t participate in the Armenian genocide, he denied it occurred. He also supported the suppression of the Kurdish language and culture. And he went off the linguistic deep end by supporting the so-called “Sun Language Theory.”

An Austrian linguist in the 1930s argued that the Sumerian language, who some thought to be the progenitor of all languages, had actually descended from Turkish. Ataturk supported this idea and at the Third Turkish Language Congress in 1936, Turkish was proclaimed the mother of all human language. Thankfully, after Ataturk died two years later, the Sun Language Theory was allowed to expire.

Belkis was rightfully proud of her country’s founder, though. Knowing some of the nuances of language and its translation into writing, I stand in awe of the man who called an entire alphabet into being in three months and implemented it among his countrymen within a year.

–Barbara Ramsey

RECENT PICTURES

PLEASE REMEMBER to visit my exhibit, Aves, at the Port Townsend Marine Science Center Gallery, which is open 12-3 pm, Friday through Sunday, through June 8. –KT

VIDEO OF THE WEEK

YOU DON’T F**K with the butter! There is literally no country on earth that comedians Foil Arms and Hogg don’t make fun of, but their favorite target is Ireland. In this video, they take aim at both the U.S. and their home country.

Snippets

THERE’S A QUIET kind of grief that settles in when you begin researching how to leave your country—not out of hatred, not because of some performative declaration, but because you still love a place that no longer feels like home …What I’m experiencing now—what thousands of others are feeling—is the ache that comes when that promise begins to feel broken. It’s not theoretical. It’s visceral. Like watching a parent decline. They’re still them, but not really. –William A. Finnegan in Persuasion

MORE OF US might begin requesting, or even building, technologies that help restore a greater sense of the real, as well as exploring strategies that use photographs and related media in more expansive and impactful ways. Might we decide that we have had enough of “consumer entitlement” and, instead, prioritize being informed citizens intent on upholding democracy? Rather than “Dream it. Type it. See it,” Adobe’s slogan acknowledging the addition of AI-driven generative fill to Photoshop, might we insist on valuing the world in which we actually live? –Fred Ritchin in Notes of a Metaphotographer

LIKE MANY NORDIC peoples, they are happiest when miserable. It’s the only way to enjoy the weather. The Danes, however, take it to the next level; there is an officially sanctioned anarchist commune (did I mention that they’re cool with rules?) in Copenhagen, called Christiania. Possibly the only hippie commune named for a seventeenth-century king, it’s also a top tourist attraction, where people from all over go to gawp at all the freedom. You have never seen a more depressed-looking group of free spirits anywhere. Imagine the IRS running a Renaissance Faire. –Quentin Hardy, “Denmark: Know Before You Invade.”

My friends and I loved watching Mazeppa on Saturdays and a live show in Joplin, Missouri when I lived there. Oh yes, and once had a personal visit with Vern Miller’s boys in Wichita. Thanks for the memories, Kerry!

When recently visiting Sydney we saw a sad, beautiful monument in one of their largest parks that was a memorial to the horrible Gallipoli Campaign in WWI (https://www.anzacmemorial.nsw.gov.au/). Ataturk was one of the military leaders who successfully defeated the ANZAC and British attack at enormous cost on both sides, and he became famous for this.