IN THE SUMMER of 2024, I started a new column, Picture & Words, in which I post and write about one photograph (most of the time). In this Wild Things Reader Digest, I’m throwing in an essay I wrote for painter Linda Okazaki’s beautiful retrospective exhibit, two slideshow videos from our trip to Norway, and some earlier articles on photographers Larry Fink, Peter Magubane, and Viktor Kolar. To read about my earlier adventures photographing birds, check out Bird Notes.

What matters

A NEW CAMERA has helped inspire me to re-focus on the poetry of light that I encounter every day. Where my bird photography was based on organized outings with a singular focus, I’m now opening up to a variety of subjects and approaches. I love the summer light on our flowers. I’ve done some portraiture. And I’m revisiting an old love—street photography.

I often hear photographers proclaim that equipment doesn’t matter—the suggestion being that their (or your) unique vision is supreme. No doubt, training one’s eye is paramount, but equipment does matter. No less an eminence than John Szarkowski, the late director of photography at MoMA, wrote a history of photography with that thesis. I’m in love with my new camera, in part because it is unfussy. It favors mechanical controls over endless submenus. The new camera has a fixed lens based on a modest wide angle (28 mm) and a large enough sensor to enable a faux zoom—basically radical cropping.

The ferry is one of my favorite places to photograph, especially during the summer when travelers from all over ride the boats to and from the Olympic Peninsula, where I live. The mid-day sun on this boy’s hair, the dark shadow cast on his neck, and a suggestion of the companionship he shares with his friend make this photograph one of my recent favorites.

The road to Oz

ON A RECENT SUNDAY afternoon at Seattle Center, I was delighted to catch the setting sun lighting up the metallic curtains that sheathe the Museum of Pop Art. In the photo, the shimmering pink and orange surface might first attract your attention, or it could be the curious boy in the lower right trying to figure out the red letters oddly suspended from a yellow tower. (I couldn’t.) You might notice how the clouds form diagonals that take you across and back again to the red letters. Or, from the boy, your eye might follow the young family up the twisty path whose curves echo the yellow climbing structure on the right and the blue-white side of the museum on the left, noticing the different ways that the two parts of the building reflect the clouded sky and trees. From there, your gaze might tumble down the silver slide, passing over the kids on top, and land on a little girl in her Sunday-best pink dress.

A wide angle lens can beautifully foreground a person or object while complicating the picture’s composition and story with compelling middle and background activity. Our knowledge of the actual relative sizes of things is playfully tricked. The happy result can be picture that engages your eye over and over, following sight lines around the frame to suss out what’s happening in each part and how the parts fit together. The wide angle takes full advantage of the camera’s capacity to register more detail in a fraction of a second than we can possibly perceive across our field of vision. The best such pictures force us to slow down and look more intensively. A glance on the phone misses too much. Unfortunately, that complexity makes photographs like this one difficult to read and appreciate on small screens and in the pre-formatted grids of social media sites. But that’s not a good enough reason to give up on making them—especially when it’s this much Sunday fun.

Chemakum joy

SINCE 1989, the Tribal Canoe Journey has become a central cultural rite for native groups of the Pacific Northwest. The traditional cedar canoes typically land in late July at a beach here in Port Townsend and the paddlers are housed and fed and celebrated for a night before continuing their journey through Puget Sound. This year, for the first time, Chemakum tribal members, the former occupants of this area, formed a greeting party to “sing in” the canoes of the Quileute. The Quileute live on the coast at La Push and are tribal brothers and sisters to the Chemakum, whose historic language, Chimakuan, they share.

I was invited to join the Chemakum greeting party, which met early in the morning to practice their songs. It was a lively gathering of family members who came from as far as Maine and Alaska. These two young Chemakum sprites, giggling and playing in the sand under that morning sun, caught my eye. In this photograph, their happy, made-up dance is caught mid twist—pure joy.

The Chemakum are featured in a series of portraits by my friend Brian Goodman that are now hanging in the Commons building at Fort Worden State Park, just a few hundred yards from this beach. For the Chemakum, who some had declared extinct, it’s a significant statement for their pictures to hang at a former army base on their former land. The exhibit is fittingly called “Still Here.” More information in the exhibit and related events—as well as a short history of the tribe—is available on the Chemakum web site.

Talk of the town

THIS RED-FOOTED BOOBY became a local celebrity in early August, attracting birders to Port Townsend from all around the Puget Sound and beyond. The bird is far out of its range in the southern seas, yet seems content to fish and hang out among the large flocks of gulls occupying our beaches. I’ve photographed this striking pelagic species many times at Kilauea National Wildlife Refuge, one of my favorite spots in Kauai. Hundreds of Red-footed booby tree nests line the cliffs there. But as in jewels, rarity is prized among birders. On the day I made my pilgrimage, I joined dozens of them, each with a scope or long lens. I’ve no explanation for why this booby has orange rather than red feet and a pink-magenta bill rather than the blue ones I’ve seen in Kauai. True, there are color variations in the species, but this booby appears to be an outlier in more ways than one.

Otra worlds

HAVING RECENTLY VISITED southern Norway, I humbly suggest a new Viking myth. In this tale, a young Thor encounters what we now call Yosemite and hammers off enormous chunks of granite and forest and carries them to Norway. While chiseling out lakes and fjords, he adds more water to achieve just the right shades of lush green. Much more water. Thor then added still more water to fill the many streams that plunge in waterfalls down granite walls into the river valleys that empty into the sea.

A couple weeks ago, our friends Sarah and Asbjorn guided us north through one of Thor’s valleys, called Setesdal, along the Otra River. At the northern end, farmers from the 15th to 20th centuries eked out a living in the rocky soil and hauled timber on long treks downriver to market. Today, a restored 19th-century steamboat takes travelers up and down the fjord. Along the river, centuries-old log storehouses with grass roofs, called stabburs, have been preserved or restored. Young climbers favor the granite walls that line the valley, but the local young often leave for better opportunities in the city. Various efforts are underway to preserve local traditions—music, clothing (we visited a museum mostly devoted to woven sweaters), and even a distinct local dialect. Sarah has written a wonderful article in the New York Times describing these endeavors.

Streets of Bergen

VARIOUS PHOTOGRAPHS that I took on a day wandering Norway’s Bergen harbor comprise this slideshow. One shot with two young runners overlooks the entire harbor. To get there, you take a popular cable car, called the Fløibanen funicular, up a mountain. Other pictures depict people and buildings and colors that caught my eye. The music, Sunday Morning, was composed by our nephew Paul Carduner and played on piano by his wife, Megan Urbach.

The images are best seen at full size; click on the little rectangle in the righthand corner of the window to expand the size.

Streets of Oslo

A slideshow of pictures from our visit to Oslo, Norway. I recommend enlarging the photos to full-screen size.

THE EVENING LIGHT on my neighbor’s sunflowers, now grown to eight-feet tall, has repeatedly drawn my eye in recent days. Walking past, I wedged my wide-angled lens inside the wire fence to get a “clean” shot, like the radiant sunflower postcards we’ve all seen. But when I edited the shoot, the ones outside the wires, even slightly out of focus, were the ones that I found evocative. Increasingly, I’m working to train myself to look for the imperfect details that complicate the subject and and subtly shifts its meanings.

AN OLD FRIEND once told me about taking his five-year-old grandson to an amusement park. When my friend suggested a ride on the ferris wheel, the boy balked. “You don’t understand, Grandpa,” he said. “I’m a sensitive boy.” I thought of that story when I saw this young fellow recently at Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle. I’m not sure what was on the other side of the glass just then—the sign suggests a tiger—but whatever it was, the glass wasn’t thick enough for this child. I love his mother’s firm grip and her seasoned look of calm. She knows her sensitive boy.

MY FRIEND BRIAN and I spent the past week traveling the West, from Rocky Mountain National Park to the (smoke-filled) Grand Tetons and finally to Yellowstone, where we spent two happy days taking photographs. This bull elk is the alpha male in a herd we discovered, along with a large group of visitors, at Mammoth Hot Springs in the northwest corner of the park. It is rutting season, a time when males compete by banging heads and issuing loud calls, known as bugling. There were several other bull elks, but all of them suddenly found grass to chew on elsewhere. The visitors were less willing to back off, despite the presence of two rangers with bull horns doing crowd control. “You, in the orange shirt, get back in your car. Orange shirt! Back in your car.”

On our side of the road a network of wooden walkways surrounded a small mountain composed of minerals deposited from the hot springs bubbling at the top. The entire herd moseyed from the other side of the road to ours. The alpha bull was last to go, rounding up stragglers before starting across, past a line of cars. Passengers huddled inside, taking pictures with their phones as the giant animal passed. Moving slowly, the alpha bull finally planted himself on the edge of the herd and let out a series of loud bugles. Brian and I stood on a nearby walkway with a dozen others. The ranger edged us back again and again, away from the alpha bull who, he said, could easily jump the rail between us. Like the other male elks, we obeyed.

P.S. I can’t leave this story without reporting an earlier elk encounter. Years ago, we went to Point Reyes to watch the elk rut with our friends Dave and Deirdre. We had no problem finding a herd, with two bulls facing off. From a reasonable distance, we watched for the action to begin. We waited patiently for almost an hour, until the evening sun started to fade. Disappointed, we finally gave up and headed for our car. As we walked away, Dave said, “Yep. No use crying over stilled elk.”

SMOKE IS DANGEROUS to breathe, but can add complexity and beauty to a photograph. In a picture, smoke evokes the mysterious or ethereal or obscure. Like fog, it offers a layering and light-filtering effect if not too dense. On a recent trip, my friend Brian Goodman and I encountered heavy smoke in Jackson, Wyoming, where the Air Quality Index the day before we arrived was in the 140s—unsafe for breathing—and in the 90s when we checked into a local motel the following evening. The smoke emanated mainly from a fire in Grand Teton National Park, the Pack Trail Fire, which has burned roughly 90,000 acres and is still not fully contained. The famous peaks themselves were barely visible—ghosts in the distance.

We saw huge swaths of burned forest on our trip through Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. These forests revealed a tragic beauty as new growth emerged among the blackened trees. I took this early-morning photograph of Miller’s Butte from a roadside stop just a few miles from the entrance to the Tetons. A large group of ducks huddled in one corner of the reeded wetland seen in the foreground. Birds’ respiratory systems, evolved for flight, are especially sensitive to smoke, which also impairs their ability to see and hunt. When they fly to a new location, they face competition from locals. Sadly, like the rest of us in the western United States, they’ve been forced to live with more fires and smoke in recent years.

Beware the murders

I KNOW I GOT OFF EASY. John Marzluff, a University of Washington professor, reports that crows can hold a grudge for as much as seventeen years, even passing them on to their offspring. A recent and widely discussed New York Times article reported incidents of crows dive-bombing a victim down the street, repeatedly slamming a person’s glass door with their beaks and, oddly, destroying dozens of cars’ windshield wipers in a parking lot. Crows are smart and can recognize and remember human faces. Even a minor offense—one guy used a rake to chase off a group of crows attacking a robin’s nest—can ignite their revenge. Not for nothing are groups of them known as a “murder” of crows.

Now for any crows reading this, I want you to know that I love you. I have often photographed you with affection and care. (That New York Times reporter is on his own.) I slipped up once, shooing you off for dipping your stolen french fries in our pond, thus creating an oil slick. But I did my time—almost six months as I recall—when you chased and screamed at me from both sides of the street every time I walked home. And even though I’m also fond of owls and eagles, I never once complained when you let off blood-curdling screams while dive-bombing their heads. I’ve also learned my lesson and won’t interfere with any future french-fry dipping. I’ll even throw in a few fries. So, truce?

PLAYING WITH THREES: I’ve had fun combining disparate images into triptychs recently, mostly based on color, texture, and design. I’ve always enjoyed how images can interact to suggest new meanings or new confluences, especially ones that are more intuitive than obvious. On the left is a recent photograph of a geothermal runoff at Yellowstone, juxtaposed to a close-up image of rust from an old shipwreck, and finally a decaying echinacea flower in my sister-in-law’s garden. I like the way the green tail on the left is echoed in the shape and color of the flower petals, whose pink-magentas are also picked up in the rust. What do you see?

I TOOK THIS PHOTO of Mt. Rainier with my iPhone from the window of an airplane. According to my software, the equivalent shutter speed was 1/10,500th of a second. Any doubts I may have had about whether the new iPhones are “real” cameras have now officially vanished.

ANIMAL, VEGETABLE, MINERAL collects thirty-two of my photographs, mostly landscapes from western parks taken over the past three years. A few birds and other animals make appearances. I made several of the pictures during my trip with Brian Goodman this fall to Rocky Mountain, Grand Tetons, and Yellowstone national parks—a glorious experience.

Rather than print and sell the book, I’ve decided to offer it free on my web site as a slideshow. The pages are arranged as spreads of two images, intentionally paired to highlight my obsessions with color, texture and pictorial design. Many reflect my current love affair with a new wide-angle lens and camera. They are best seen on a large screen. If you do take a look, I’d love to hear any feelings or thoughts that you have.

A PRE-PANDEMIC trip to four cities in Portugal and two in Spain yielded a trove of images that I’ve recently rediscovered, refined, and newly released in a free online book, Iberia. Using a small Sony camera and wide angle lens, I had enormous fun with the region’s angled vistas and rich colors, such as the orange-roofed casas that steeply line the Douro River in Porto. That autumn, the Portuguese were celebrating the beginning of the school year at universities in Coimbra and Lisbon with festive parades through the streets. Entering freshman were decked in brightly colored outfits and silly hats, while the senior class members, like the young women below, donned sober academic black robes yet conveyed the same infectiously joyous spirit.

This is the third book of photographs I’ve recently made available free online in the form of a slideshow. A fourth is in the works. There’s also link for a free download of my multimedia Yosemite book. A friend has urged me to write about my thoughts behind this decision, and perhaps I will at a later date. For now, suffice it to say that art and commerce are at best an uneasy mix (witness the $120,000 duct-taped banana). It’s more important to me that the pictures are seen.

The color of dreams

Note: Linda Okazaki is one of my favorite artists of the Pacific Northwest. Her brilliant retrospective has just concluded at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, but the associated book is available from their bookstore for $24. For the book I wrote this essay, which is reprinted with permission from Chief Curator Greg Robinson, who organized the exhibit.

IF YOU WERE encountering Linda Okazaki’s paintings for the first time, and knew little of her life, what might you see in them?

You might notice the water—streams, lakes, seas, and what look like enormous baths. “Water for me is like the sky for other painters,” she says, with shapes and colors that can be chosen to reflect a mood or complete a composition. Water is the ultimate shapeshifter, even morphing into human form over eons. For a painter of stories, that makes it the most fluid of metaphors, signifying everything from the womb that bears life to the river crossed to we know not where.

Okazaki’s color stands out, too, for its vividness and luminescence. Joyful colors play against sober themes while darker ones intensify the solemn notes. Okazaki is a lifelong student of color, particularly the myriad ways in which it conveys emotion. She wrote her master’s thesis on a 19th century theory of color that still informs her work.

Birds are prominent, especially crows and ravens. These, too, are metaphorically rich figures that appear in the oldest myths and stories, including among Native American tribes in the Pacific Northwest, where she lives. Other creatures turn up as well, such as fish, dogs (in one case, a specific dog), cats, and coyotes. They, too, are story carriers.

You might observe that many of her paintings depict a woman, sometimes clothed, sometimes nude, who appears to be part of a larger story. She is swimming outdoors or reclining indoors or up in the sky and often accompanied by birds or other animals. Occasionally there are other people in the paintings, including a few historical artists with whom she imagines dialogues in her journal. The figures are drawn expertly but not realistically or proportionally, and usually in shallow perspective.

The water, the colors, the birds, and the woman—all are imbued with emotion. They comprise a story that is just beyond our grasp, like a dream. You might suppose, correctly, that many of the images come from dreams, and that the woman in the dreams, like most of us, is trying to work something out… Read and see more.

Remembering Peter

IN 1995, I INVITED Peter Magubane, the great South African photographer, to the Bay Area, where he stayed with my wife and me. He came to judge the entries to that year’s Mother Jones International Documentary Fund awards, which I had created with photographers Ken Light and Michelle Vignes. Two years later, we again invited him to the U.S. to receive the fund’s Leica Lifetime Achievement Award in New York, where he shared a dinner table with Leonard Nimoy and Gene Wilder.

There have recently been tributes to Peter, who died last Monday, including a lengthy one in the New York Times. My story today concerns a different side of the man who endured beatings, internal exile, and solitary confinements to photograph the horrors of apartheid and the struggle against it.

After his friend Nelson Mandela was elected president in 1994, Peter undertook a project to document life in the more rural provinces of South Africa. He told us he had traveled with a white journalist and on one occasion they had stopped at the home of an Afrikaner farmer. Peter stuck out his hand, but the farmer refused to shake it. The journalist chatted with the farmer for a few more minutes and, as they were leaving, Peter handed the farmer his business card. “He put my card in his pocket—next to his heart,” Peter told us and laughed.

We enjoyed dinners and parties with Peter during the week he stayed with us and we heard many more stories, some harrowing and others hilarious. On the day he was to leave, I called a cab to take him to the airport and when it came, we embraced at the door. I handed him my business card, smiled, and said, “I hope you will put this card next to your heart.”

“Oh, no,” said Peter, “I think I will put it in my back pocket.”

Rest in peace, my friend.

One more round for Larry

WHEN I LEFT Mother Jones in 1998, I lost touch with many of the photographers I’d worked with at the magazine. But Larry Fink called me later that year when he was traveling through San Francisco and we met for lunch. He gave me his latest book, Boxers, generously including a signed print. The photograph is square and two thirds of it shows a boxer’s broad back. The back, Larry explained, is the source of a boxer’s power, balance, and agility. It reduces injury by absorbing blows, which extends a boxer’s endurance in the ring.

Larry didn’t have a broad back—with his beret, he looked the part of a ‘60s beat. But he did have a strong one. He endured, living to 82, still taking pictures, making music and poetry, and tending to his Pennsylvania farm.

At lunch, he reminded me of something Katherine Dunn had written in Mother Jones that he included in the introduction to his book. Dunn had earlier produced her own book on boxers, One Ring Circus. Larry quoted her:

A boxing gym is place where men are allowed to be kind to one another. Any man will gently wipe any other man’s face with a towel, fix his helmet straps, tie his shoes, massage his tense shoulders… This tender, respectful nurturing is absolutely necessary because of one magic ingredient: the gloves. Anyone wearing bulky, fingerless gloves is unable to blow his nose or take a drink of water by himself. Those who are not gloved up help those who are. From this central fact radiates the whole demeanor of the game.

Larry like to greet me as a comrade since I’d worked for a leftwing magazine and he’d been raised by communists. He proudly told me his sister, a lawyer, was still actively defending the 1971 Attica riot prisoners. But he is best known for his series of candid, flash images taken at Studio 54, the disco club that celebrities and the wealthy flocked to in New York in the 1980s. He was inspired, he said, by the Weimar paintings of George Grosz and Otto Dix depicting grotesque plutocrats. His subject was class and he had a satiric bite, but also, like his boxers, a tender side. He was easily amused by our foibles, but not mean. A master of irony, he offered penetrating looks into a tragically compromised world while holding a gleam in his eye.

In fact, I suspect the gleam was part of Larry’s toolkit. People photographers must devise ways to make their subjects less self-conscious in front of the camera. One way is perseverance—staying with the subject long enough that the camera itself becomes, if not invisible, at least less intrusive. But there are others. My friend, the late photographer Michelle Vignes, had a childhood condition that gave her a permanent limp. She once told me her gait disarmed people, aroused their sympathy, and made access to their lives easier. And I for one found Larry’s bemusement with the world, combined with a seriousness of purpose, both charming and disarming.

There have been several tributes by people who knew him better than I did. Lucy Sante wrote a good one for Vanity Fair, where Larry was a long-time contributor. As it happens, I called Larry earlier year to ask him to look at my bird photographs and, if moved to do so, write a blurb for my book, Aves. He wrote, “The light is exquisite… there is sensual magic flying near.” I daresay that could also be said of Larry’s extraordinary life and work.

Man of marble

“Ostrava is Dickens’s world come to life. It is the ghost of the communist state, which preserved the Industrial Revolution in a time capsule. It is also the unlikely home of one of the finest photographers in Europe.” –Frank Viviano

BRUTALISM. That word aptly describes so much about the Czech city of Ostrava. The rows of concrete housing projects built during the Soviet occupation. The coal mines and steel plants symbolizing communism’s muscular industrialism and the harsh conditions of the workers who toiled there. The Nazi’s murder the city’s Jewish population during WWII and the massacre of German-speaking civilians following the war. The punishments for deviation from dogma, including those meted out to Viktor Kolář’s father, a filmmaker, and later to Viktor himself.

As a photographer, Viktor Kolář’s great achievement, over six decades, has been to convey the humanity of Ostrava’s people amidst the brutal suffering and humiliations he has shared with them. His home is a city of 280,000 in the Czech Republic, bordered by Germany and Poland to the north and east, and within striking distance of Moscow. In 1968, Moscow did strike, ending the Prague Spring, a brief attempt at liberalization. In its wake, Viktor emigrated to Canada for five years, during which his dexterity as a street photographer caught the attention of Cornell Capa1 among others. Despite Capa’s cautioning, Viktor returned to Ostrava, where he was literally forced underground, clandestinely photographing coal miners.

From its central location, Czech art and photography also absorbed the influences of the movements swirling through the past century—from Germany (Bauhaus modernism), France (Surrealism), and Russia (Constructivism).2 Viktor’s major influence was Henri Cartier-Bresson, known for a dynamic style of street photography he famously described as seeking the “decisive moment.” More than any photographer I’ve known, Viktor also embodies a distinguishing feature of social documentary photography, an embedded, intensive engagement with the subjects of his pictures. “The people I photograph have secret resources,” Viktor told a reporter years ago, “secret mechanisms that keep them sane, that keep them going.”

I MET VIKTOR only once, when he traveled to San Francisco in 1991 to receive an award and grant from the Mother Jones International Fund for Documentary Photography, which I then directed. I later commissioned a story from Frank Viviano to accompany an essay of Viktor’s photographs in Mother Jones. Recently, I’ve been in email contact with Viktor, now in his eighties, who describes Ostrava as experiencing a less-than-successful privatization of the major industries—the last coal was mined in 1994. He says democracy initiated a process of “growing up” from the paternalism of Big-Brother communism. “People learned to take responsibility for their lives, a painful process that is far from being finished,” he says. Consumerism has spread. A threat, he suggests, now comes from the oligarchs who have taken control of the media, but a new generation is learning to defend its freedom and self-expression. As dedicated to his fellow Ostravans as he as always been, he remains sober about its prospects. As he told Viviano thirty years ago, “Sentimentality will not save us.”

Editor’s Note: The title, Man of Marble, is a reference to the 1977 film by Polish director, Andrejez Wajda, about the fall from grace of a bricklayer made a hero by communist propagandists and a young filmmaker who later uncovers his story. Viktor reminds me of that brave filmmaker. On my web site, I’ve reproduced Frank Viviano’s essay from 1994, after he visited Viktor in Ostrava, which is an incisive observation of the changes in central Europe shortly after the fall of communism. I’ve included as a small selection of Viktor’s photographs, with his commentary. For more pictures, I urge you to visit Viktor’s web site.

1 Cornell Capa was a photographer and founder of the International Center of Photography in New York. He was the brother of Robert Capa, a co-founder with Henri Cartier-Bresson of the Magnum photo agency who photographed the Spanish Civil War and battles of WWII, including D-day. He was killed in 1954 when he stepped on a mine while covering the war in Vietnam.

2 There are many superb Czech photographers. I’ve encountered three working in the documentary tradition, including Viktor. Antonin Kratochvil photographed stories for me at Mother Jones, including a darker and more profound depiction of Czechoslovakia in the aftermath of the Velvet Revolution than the happy images saturating the major media at the time. I once met Josef Koudelka at a gallery in San Francisco, and have a photograph from his book Gypsies in my living room.

Alive with color

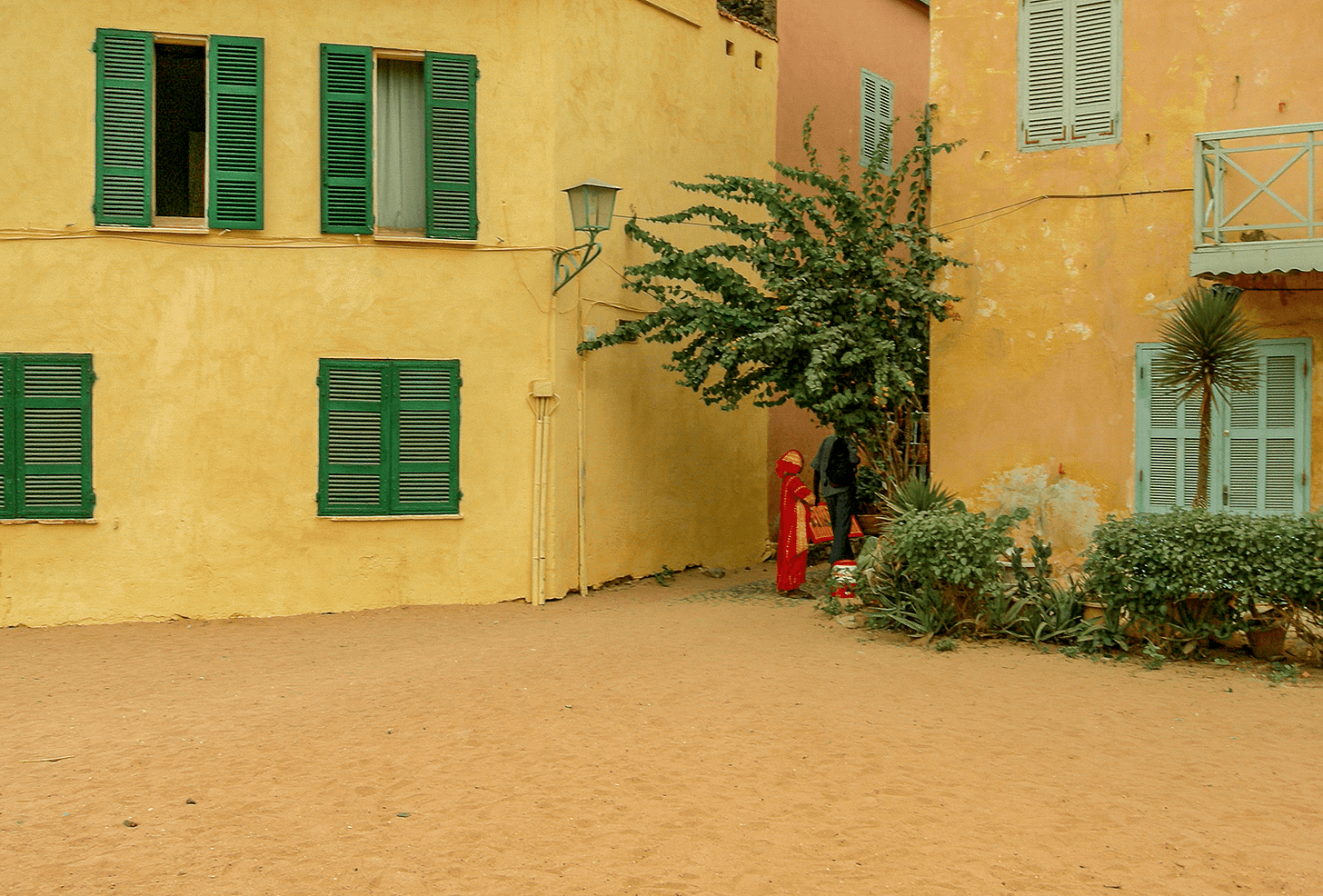

I VISITED SENEGAL nearly twenty years ago and took photographs with a wide-angle point-and-shoot Nikon. I occasionally revisit this set of pictures, so different from my bird photographs of recent years. For a magazine article at the time, I described Senegal as “an admixture of the sacred and the secular, of an Islam suffused with tribal animism and colonial Christianity, of the medieval and the modern.” There were, for example, the women. The Senegalese are easily one of the most fashion conscious people on earth. In this conservative Moslem culture, I never saw women and men touching or kissing in public, but the women were invariably coiffed and made-up and beautifully dressed. They wore both western clothing and boubous, a shoulder to ankle gown with matching head wrap made from silk, or embroidered cotton, or cloth dyed in brightly colored patterns.

Since my wife is a fiber artist, we were invited one afternoon to visit a dye workshop, an unassuming cinder-block building with tubs of brilliant colors in the back and, in the front, a table laid with magnificently designed fabrics. On another afternoon we attended a backyard party where the Senagalese women were dressed to the nines. West Africa is justly famed for its music and, on a patio, a group of Serer women danced in athletic, almost jointless spasms of movement, kicking their feet high above their heads in time to the drums’ rhythms.

We also took a boat to Goreé Island, the infamous departure point for thousands of slaves shipped to the Americas. In contrast to its troubled history, Goreé is beautiful, with colonial buildings painted in ochres and reds, and children playing soccer on the beach, and open air cafes. In one sandy courtyard, I saw a child draped in red standing—selling? waiting for someone? As with so many of Senegal’s surprises I couldn’t say. I simply savored the boundless interplay of color and culture.