Looking back

A top predator, Senegal surprises, and the untimely death of Lat Conerly

BIRDS

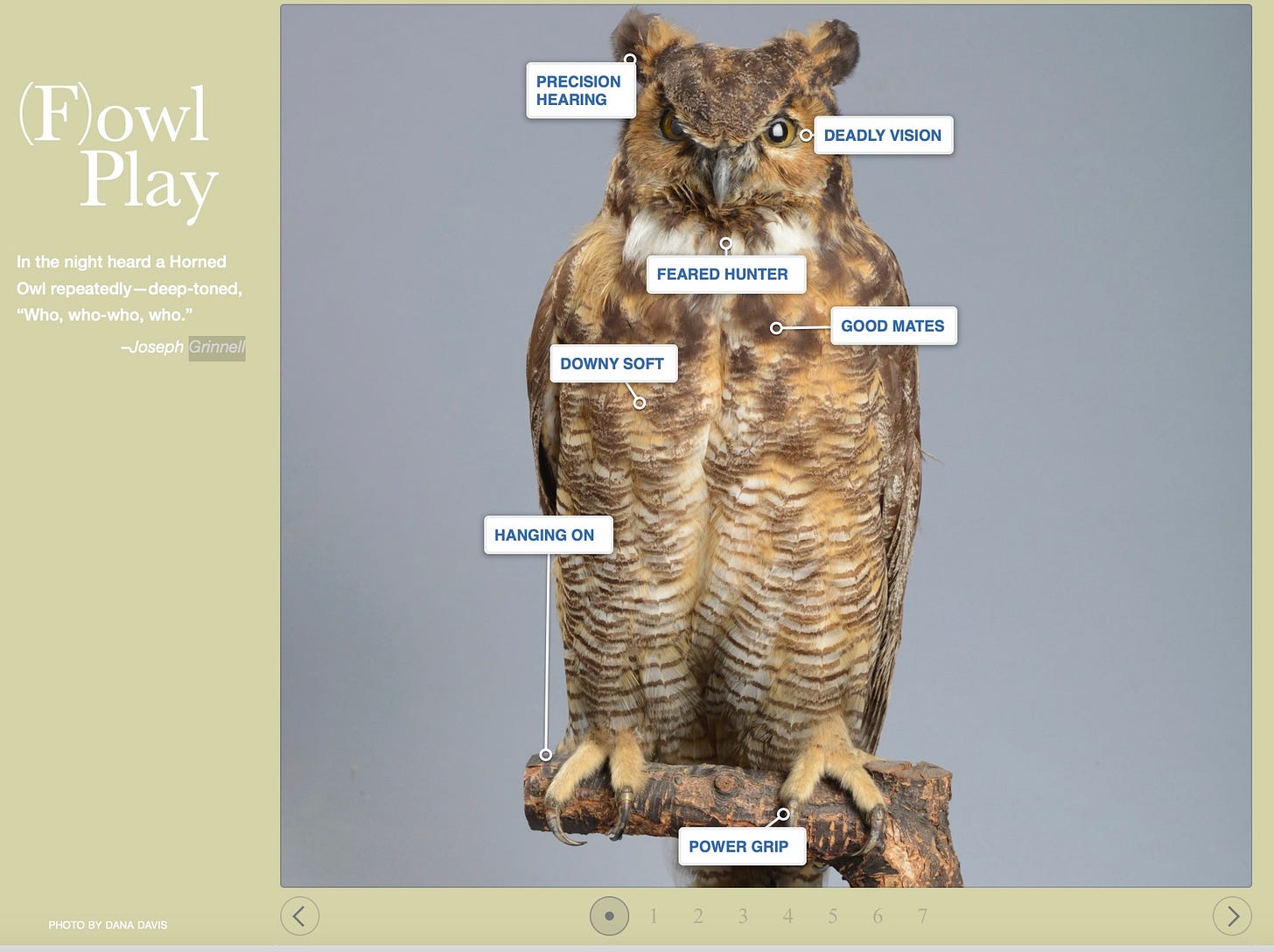

The great horned hunter

FOR THE 150TH Anniversary of the Yosemite Charter, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, I co-curated an exhibition and produced a multimedia iBook for the California Historical Society. Yosemite: A Storied Landscape is free on Apple Books. It includes a small interactive feature on one of the park’s top predators, the Great Horned Owl. The above page from the book describes the characteristics that make this owl an outstanding hunter.

Precision Hearing. The facial dish directs sound to the ears, and the right ear is positioned higher than the left, causing sounds to reach one ear a fraction of a second before the other. The owl tilts and turns its head until the sounds align directly with the location of its prey.

Deadly Vision. The owl’s large eyes (equivalent to grapefruits on a human) have pupils that open widely for superior night vision. The eyes don’t move in their sockets, but the owl can swivel its head up to 270 degrees.

Feared Hunter. The Great Horned Owl hunts prey two to three times its size, including porcupines, marmots, and skunks. Once, the remains of fifty-seven striped skunks were found in a single owl nest.

Good Mates. The female Great Horned Owl is larger than her mate, but the male has a larger voice box and a deeper voice. Pairs often call together, with audible differences in pitch.

Downy soft. The owl’s extremely soft feathers insulate against cold winter weather and help it fly quietly in pursuit of prey. Silent flight enables increasingly more accurate audio triangulation of the prey's location as the owl closes in.

Power Grip. When clenched, a Great Horned Owl’s strong talons require a force of twenty-eight pounds to open. It uses this deadly grip to sever the spine of large prey.

Hanging on. The Great Horned Owl, which lives throughout North America, has an average life span in the wild of five to fifteen years. The oldest on record, found in Ohio in 2005, was twenty-eight years old.

For more, my Port Townsend friend Andrea Guarino-Slemmons took an oustanding series of photographs of a Great Horned Owl nest earlier this year.

FROM THE ARCHIVES

Alive with color

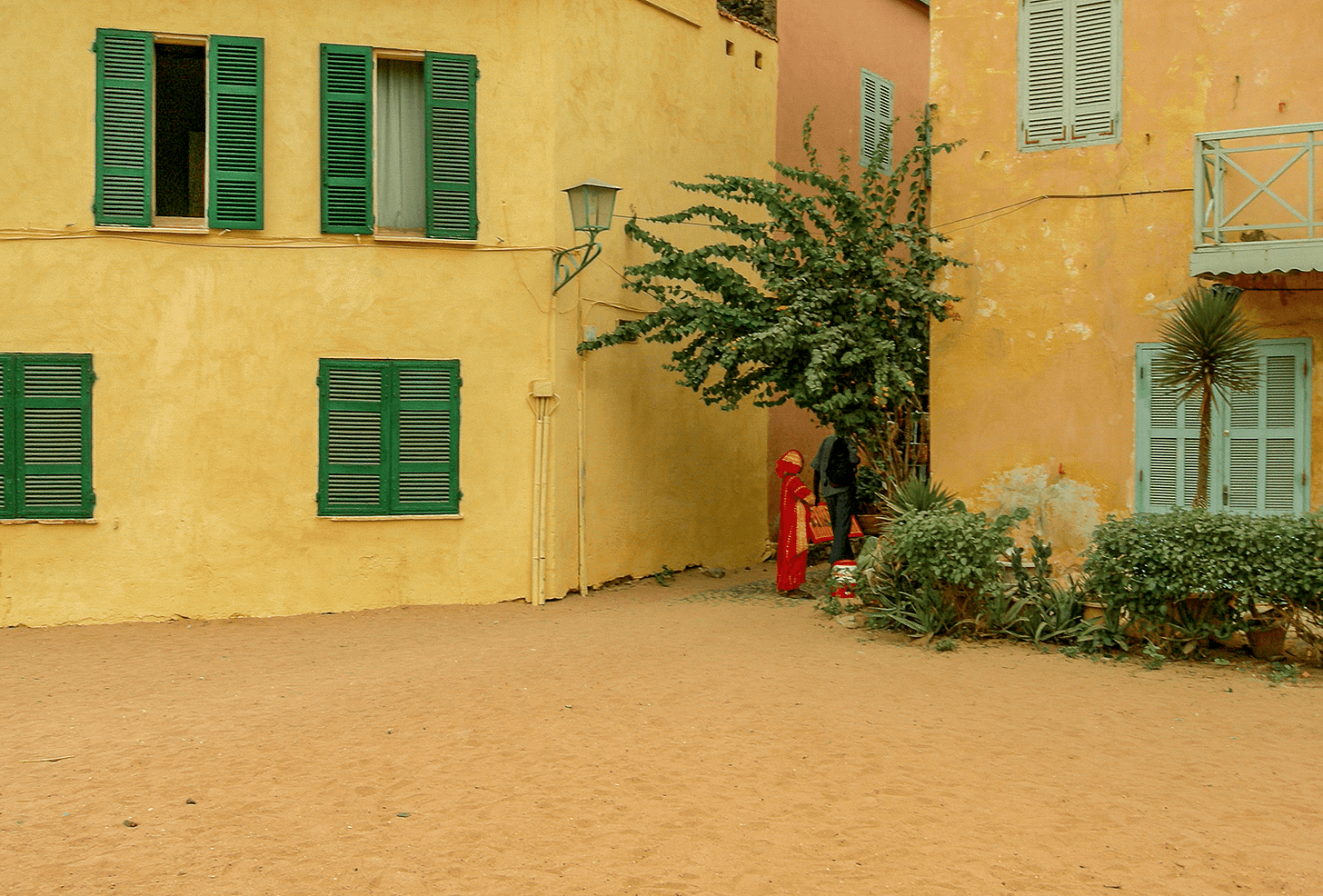

I VISITED SENEGAL nearly twenty years ago and took photographs with a wide-angle point-and-shoot Nikon. I occasionally revisit this set of pictures, so different from my bird photographs of recent years. For a magazine article at the time, I described Senegal as “an admixture of the sacred and the secular, of an Islam suffused with tribal animism and colonial Christianity, of the medieval and the modern.” There were, for example, the women. The Senegalese are easily one of the most fashion conscious people on earth. In this conservative Moslem culture, I never saw women and men touching or kissing in public, but the women were invariably coiffed and made-up and beautifully dressed. They wore both western clothing and boubous, a shoulder to ankle gown with matching head wrap made from silk, or embroidered cotton, or cloth dyed in brightly colored patterns.

Since my wife is a fiber artist, we were invited one afternoon to visit a dye workshop, an unassuming cinder-block building with tubs of brilliant colors in the back and, in the front, a table laid with magnificently designed fabrics. On another afternoon we attended a backyard party where the Senagalese women were dressed to the nines. West Africa is justly famed for its music and, on a patio, a group of Serer women danced in athletic, almost jointless spasms of movement, kicking their feet high above their heads in time to the drums’ rhythms.

We also took a boat to Goreé Island, the infamous departure point for thousands of slaves shipped to the Americas. In contrast to its troubled history, Goreé is beautiful, with colonial buildings painted in ochres and reds, and children playing soccer on the beach, and open air cafes. In one sandy courtyard, I saw a child draped in red standing—selling? waiting for someone? As with so many of Senegal’s surprises I couldn’t say. I simply savored the boundless interplay of color and culture.

WHAT’S BARBARA THINKING? A PERSONAL HISTORY

The Death of Lat Conerly

My grandfather, who grew up in Alabama in the 1880’s, was named William Latson Conerly, but everyone called him Lat. He had a brother named Otho Samfort Conerly. Everyone called him Bill. No reasons ever given, just Lat and Bill. Lat was an upstanding figure in the community, married to a schoolteacher and known as a reliable worker at the local lumber mill. His brother Bill was famed for his skills at hunting and fishing but was a bit of a reprobate who drank, gambled, and frequented establishments where those activities were encouraged.

Lat had rheumatic heart disease. Rarely seen in America these days, it’s generally caused by a tangled thread of germs, poverty, and genetics. Even today it remains a bit mysterious to researchers. Back in Lat’s day, it was greatly feared, sometimes survivable, often fatal. His case was initially mild enough that he made it to age fifty and fathered five children.

Then his symptoms grew worse. The main heart chamber of his heart strained with the difficulty of trying to pump blood from his lungs to the rest of his body. He became short of breath on any uphill climb. Grandfather Lat shrugged it off for a while but finally, on an afternoon in 1931, he decided to visit the town’s revered doctor, Dr. Bedsole.

Dr. Bedsole’s office was on the second floor of a building that was a nice flat walk a few blocks from the house Lat had built for his family ten years earlier. Lat knew he could make the walk easily, but doubted he could climb the stairs. Once at their base, he flagged down a passing child and asked him to run upstairs and tell Dr. Bedsole to please come down. The child was instructed to say that “Mr. William Latson Conerly needs him. He’s down on the street and can’t come up the stairs.” The child did.

Dr. Bedsole was having a busy day and only half heard the boy’s recitation. What stood out to him was the name “William Conerly,” which he assumed meant Bill Conerly, my grandfather’s brother. Bill’s drinking often resulted in injuries that the doctor had to repair, and on this day, Dr. Bedsole had had enough. “You tell that man if he wants to see me, he can come up those stairs himself!” he said.

Hearing this reply, my grandfather figured that if Dr. Bedsole thought he could make it up the stairs, then maybe he could. He gathered himself together and climbed. At the very top, Lat grew lightheaded and stumbled into the office. Probably the diseased cords that tethered his mitral valve finally snapped. Dr. Bedsole, horrified at the gray face of his friend, helped him onto the couch. He did what could, but Lat died the next day.

My mother, who was nine at the time, said Dr. Bedsole never forgave himself. He became a kind of substitute father to her. With his encouragement, she went on to medical school and became a doctor, an uncommon fate for little Alabama girls growing up fatherless in the Depression.

Now I am old and thinking about this history. My mitral valve isn’t working right and my echocardiogram hints that one of its leaflets may be flapping unnaturally, as if no longer properly tethered. I want Dr. Bedsole to come down those stairs and fix me, at last. –Barbara Ramsey

EXHIBITS

Collective Visions

THE PHOTOGRAPH Red-tailed Tropicbird has been selected to hang in the 17th Annual CVG Show at the Collective Visions Gallery in Bremerton, Washington. It was chosen from hundreds of entries by juror Greg Robinson, Chief Curator of the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art. The show will open on January 13 and run through February 23 at the gallery, which is located at 331 Pacific Avenue in Bremerton. If you’re in the area, I hope you will visit. On my web site, I’ve written more about my encounter with this bird at the Kilauea National Wildlife Refuge in Kauai.

Next edition:

Debunking the Fermi paradox, defending documentary, and the wonders of Wood River Delta.

Please add your comments by clicking on the speech icon at the top or bottom. Subscribe if you haven’t already. And please send Wild Things to friends who might be interested. –Kerry

The most beautiful response to cardiac issues ever written. What a heartbreaking, perfect piece.