PHOTOGRAPHY

Yosemite’s redemption story

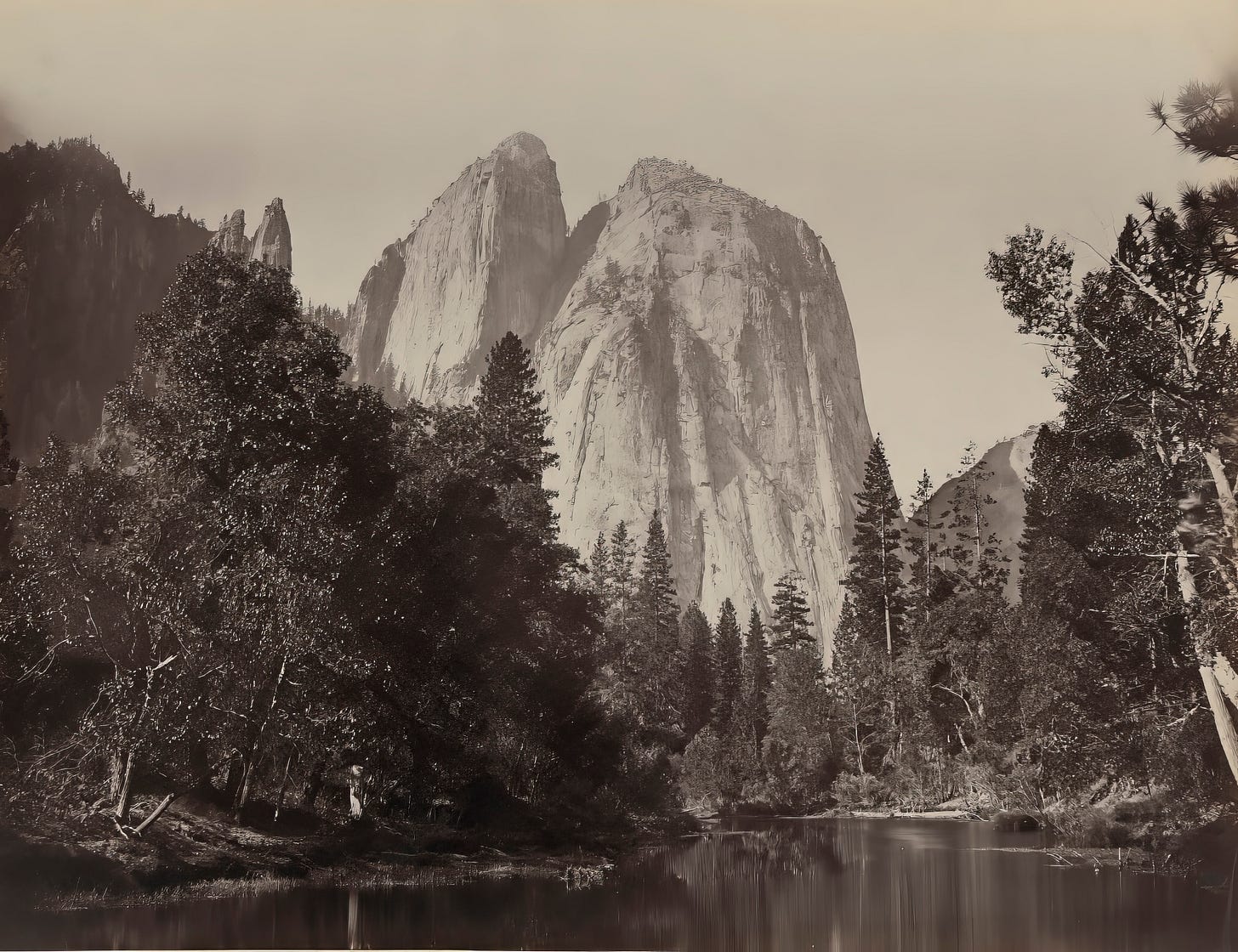

WHEN CARLETON WATKINS exhibited his photographs of Yosemite in New York City in 1862, he could hardly have guessed at the show’s artistic and political repercussions. “As specimens of photographic art they are unequaled,” wrote a New York Times critic of the exhibit. “Nothing in the way of landscapes can be more impressive.” With his mammoth camera and 18 x 22-inch glass-plate negatives, Watkins had virtually invented Western landscape photography. But Watkins’ exhibit at New York’s Goupil Gallery did more than lay down a new marker for landscape photography. For many Americans, east and west, his photographs helped transform Yosemite into a place of legend.

Watkins’ New York debut directly followed the Mathew Brady Gallery exhibit of Alexander Gardner’s photographs of the dead at the Battle of Antietam. The gruesome images fascinated and horrified New Yorkers, who lined up to see them. Watkins photographs naturally had a more salutary effect. Following the exhibit, Yosemite was championed by leading voices as a healing symbol for America. Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune and Thomas Starr King of Boston Evening Transcript extolled the ennobling virtues of Yosemite’s grandeur in contrast to the sectional political strife that drove the nation to civil war. In the last year of the war, Frederick Law Olmsted wrote that “contemplation of natural scenery” promotes the “health and vigor” of the mind and body, echoing the idea of Yosemite as a place for America’s wounded psyche to heal.

Perhaps. But this view overlooked the state’s forcible removal of the Ahwahneechee in 1851. Late in life, Chief Tenaya’s granddaughter recalled seeing her people sifting through piles of ashes to find edible acorns after the Mariposa Battalion burned their winter food cache. Most had already been removed to a reservation in the Central Valley by the time Watkins began his Yosemite project in 1861.

When a Civil War-weary Congress considered legislation to protect Yosemite, Watkins’ pictures lent support to the law’s passage. California Senator John Conness reportedly passed them around before introducing the Yosemite Grant—the first act of the federal government to protect a scenic landscape—in the spring of 1864. Congress was just emerging from the bruising battle over the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery. It was the right moment. The act sailed through both houses with little discussion and was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30, 1864. For many, Yosemite’s beauty seemed to confer the sense of divine grace that Lincoln appealed to in his Second Inaugural: “With malice toward none, with charity for all… let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds.”

—Adapted from “Yosemite: A Storied Landscape,” which I created for California Historical Society and is free to download on Apple Books.

CULTURES

Basque sheepherders of the west

IN 1923, THE YELLOWSTONE prequel starring Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren (ah, Helen), Ford plays a cattle rancher, Jacob Dutton, who is ambushed and nearly killed. Others in his party don’t make it. The murderers are led by a sheepherder. In this age-old story we’re on the side of the Duttons. Cattle ranchers are the good guys and nomadic sheepherders are the bad guys. Same as it ever was.

Many of those sheepherders were Basque. They are the oldest known indigenous group in Europe and speak a language unrelated to any other. Paul, one of my close friends, is of Basque heritage and I have been to their historic homeland in and around the Pyrenees mountains of southwestern France and northwestern Spain. When you arrive at the airport in Biarritz, France, the sign on the terminal welcomes you to “Pays Basque”—Basque Nation. Paul still visits his uncles and cousins there—one restored the family’s 17th-century stone farm house—and some are still agitating for an independent Pays Basque.

John Muir called the sheep “hooved locusts” and helped rally the Army to banish the sheepherders from Yosemite, where they pastured their flocks in meadows below Mt. Dana. Long vilified in official histories, the sheepherders are now thought to have played a positive environmental role in the park. The small fires they burned to create meadows for grazing —like those used earlier by Ahwahneechee to cultivate their acorn forest—helped prevent catastrophic fires.

In Yosemite and elsewhere, the Basque herders invented their own language comprised of arborglyphs—symbols and letters carved into the bark of lodgepole pines and aspens. One park historian recorded over 1700 of them and there are tours of arboglyphs in California, Nevada, Idaho and Oregon. Their coded communication helped the shepherds evade the Army patrols and was a balm for their isolation.

Paul’s great grandfather and his three brothers emigrated to the United States in the 1860s. After working as herders, they acquired a ranch near Salinas that eventually expanded to 5,000 acres. Like others who came in the late 19th and early 20th century, they were young men looking to make some money. They were aided by a network of Basque hotels, called Ostatua, that criss-crossed the country. At dockside, the men were greeted in their language, a comfort after a long journey on a cargo ship, and given a place to stay. But sheepherding was a lonely life, different from the one back home, and the many weeks and months alone took a toll. Over a third eventually returned to Europe with whatever money they had saved.

The range wars also took a toll. Like the fictional Duttons, cattle ranchers fought sheepherders with barbed wire, guns, and political power. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, which restricted grazing on public lands, was a devastating blow. While it helped address overgrazing on public lands, the local distribution of parcels was controlled by ranchers. The government welcomed the Basque sheepherders back, however, when the Army needed wool for uniforms and blankets during WWII. Paul remembers his grandfather bringing whiskey and fruit to the Basques tending huge herds at Fort Ord on Monterey Bay.

Large Basque communities in Idaho and Nevada still celebrate their heritage in annual festivals of song and dance featuring traditional foods. A few of the old Ostatua remain. Some, Paul tells me, welcome everyone for food and drink, but to rent a room, you must prove you’re Basque.

ART

Across the divide

CONGRESS UNANIMOUSLY PASSED the Yosemite Grant in 1864 when the country was engaged in a fratricidal war. The vote came on the heels of the divisive congressional debate over the 13th Amendment to the Constitution to end slavery. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the grant establishing the nation’s first protected wilderness, many interpreted it as an early act of reconciliation. Even in the midst of our bloodiest war, we were able to agree that a place of such beauty, a land that makes our spirits soar, individually and as a people, should be preserved for current and future generations.

Six decades later, in 1927, a Japanese immigrant and artist, Chiura Obata, was invited to accompany a small group of artists on a summer journey to Yosemite. Despite the xenophobic climate in California when Obata arrived early in the century, over time he had received accolades for his work. But it was Obata’s Yosemite journey that summer that inspired his best-known paintings. He called it ““the greatest harvest of my whole life and future in painting.” From his Sierra camp, he wrote to his wife Haruko, “After the passing of a thunderstorm, the freshly brightened colors vanish as the evening falls. As the deep blues turn to purple, one can still hear the melody of a thousand streams.”

Over six weeks, Obata created an estimated one hundred and fifty sumi-e drawings and watercolors, almost single-handedly renewing the fine painting tradition in Yosemite. Returning for two years to Japan in 1929, Obata employed some of that nation’s finest woodcut artists to make block prints from the paintings. A perfectionist, he often used one hundred or more passes to achieve subtle color wash effects in a medium originally designed for flat color.

In 1932, Obata was appointed as an art instructor at UC Berkeley and mounted several exhibitions of his work. His reputation grew over the next decade. But after the outbreak of WWII, and over the protestations of UC President Robert Sproul, Obata was sent to a the Tanforan Assembly Center and then the Japanese-American internment camp in Topaz, located in the Utah desert. Remarkably, he established art schools in both places and continued to produce paintings in the camp. After the war, he returned to the university, where he taught for another eight years.

Obata’s work as an artist and teacher introduced sumi-e painting and other Japanese methods and aesthetic traditions to numerous American artists. Several major museums have collected his work. Summarizing his legacy, art historian Susan Landauer writes: “An individualist, Obata believed in giving free range to his poetic voice and in making the best of his resources, which, encompassing the traditions and innovations of both the East and the West, were vast indeed. Finally, Obata’s accomplishment reflects the courage with which he faced the project of being an Asian artist in a hostile society. It was in order to transcend that hostility that he kept his gaze trained so intently on the timeless beauty of the California landscape.”

Obata died in 1975 at the age of 89. He did not live to see President Ronald Reagan sign the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which included an apology and compensation for eighty-two thousand Americans of Japanese descent who were incacerated in camps during WWII. And four years ago, the California legislature designated a portion of Highway 120 running through Yosemite as the “Chiura Obata Great Nature Memorial Highway.”

Chiura Obata and his paintings are featured in a chapter of the book I edited and designed for an exhibition I co-curated, Yosemite: A Storied Landscape, at the California Historical Society in San Francisco in 2015. The book is available as a free download on Apple Books. It includes an interactive feature showing how Obata achieved nuanced color effects in his block prints.

ORIGINS OF THE PARK

The chef who helped create the National Park Service

FOR RENOWNED CHEF Tie Sing, things were going perfectly well until his mules fell off a cliff.

He had been the obvious choice to cook for the so-called Mather Mountain Party, a taxing twelve-day trip into the high Sierra in July 1915. Sixteen years earlier, in 1899, and during the height of anti-Chinese discrimination, the U.S. Geological Survey in the Sierra had already honored Sing’s culinary prowess by giving the name “Sing Peak” to a 10,552-foot mountain peak on the southern edge of Yosemite.

Convened by Stephen Mather to drum up support for a new National Park Service, the 1915 party of fifteen prominent businessmen, politicians, and journalists included leaders of National Geographic Society, the American Museum of Natural History, and Southern Pacific Railway. Mather, the Undersecretary of the Interior, was also a businessman who made a fortune with his 20-mule Team Borax company.

Thanks to Tie Sing, these muckety-mucks traveled in style, with sumptuous meals set with china and fine silver on white linen tablecloths that he and his assistant laundered daily. When, early in the trip, two mules tumbled off a 300-foot cliff with cooking supplies, Sing was bereft. The pots and pans were one thing. But one of the mules had carried his precious sourdough starter. The master chef made do, as always, with aplomb. He draped his biscuit dough over working mules, whose body heat helped the dough rise.

In written accounts of the excursion, praise for his meals sometimes overshadows the mountain scenery. And Mather’s gambit worked. His camping buddies turned into powerful lobbyists for a new federal agency to oversee the parks. The menus that summer helped inspire the creation of National Park Service the following year. They included a Farewell Dinner on July 28 of trout and venison, with a special dessert, a pastry that enclosed a “future fortune” for each of the Mountain Party. Mather’s read: “The sound of your laughter will fill the mountains when you are in the sky.”

Yosemite Ranger YenYen Chan has created a video of Chinese immigrant contributions to the park, including those of Tie Sing. The multimedia ebook I created for the California Historical Society exhibit, Yosemite: A Storied Landscape, is a free download in Apple Books.

NATURAL HISTORY

Hunting the bear

IN AN EXTRAORDINARY 1918 letter, a rancher named Robert Wellman recounted how he and a friend had killed one of Yosemite’s last two Grizzly bears thirty years earlier. Using a dead cow as bait, Wellman had lured the bear below a tree platform he’d built. From there, he shot and wounded the bear, and then climbed down the tree to finish him off.

“My rifle barked, sending a ball under the base of his ear,” Wellman wrote. “He rolled over on his side [and] a few convulsive struggles shook his frame. He raised one huge fore arm and waved it back and forth a few times. Then it dropped. The King of the Sierra was dead. We gazed on the prostrate beast for some moments in silence.”

Nearly 130 years after the bear was slain, I tracked down his pelt and put it on public display.

Wellman sent his hand-written letter to Joseph Grinnell, the founder and director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley, who had requested the account. Starting in the early twentieth century, Grinnell and his successors continually collected vertebrate pelts and skeletons in California, meticulously recording their findings in thousands of blue notebooks that line one of the museum’s walls.

A pioneer of the science of ecology, Grinnell had long warned against eliminating the Grizzly bear and other top predators. Ten thousand once roamed the state. Though the iconic bear still graces the state flag, the last recorded California Grizzly was killed in 1922, three years after Wellman wrote his letter.

While researching materials for a Yosemite exhibit at the California Historical Society, I discovered Grinnell’s correspondence with Wellman in the university library. From my days as an editor on campus, I’d also become acquainted with the field biologists at the museum. I’d even gone with them on a field trip to Yosemite, where I learned to trap and skin voles.

The vole-sized specimens are collected in metal drawers in the museum, but larger animals are housed in a climate-controlled storage facility, where their fresh carcasses are cleaned by insects and their skins labeled and hung. Aware of Grinnell’s tenacity, I strongly suspected Wellman’s Grizzly was there. But when I asked my friends at the museum, they grumbled about finding a particular pelt among the hundreds hanging in storage.

In the end, though, they did find the bear. Grinnell, it turned out, had acquired the skin from artist Thomas Hill, who had bought it from Wellman and hung it in his Yosemite studio. From Berkeley, the bear made its way to our exhibit in San Francisco, where we also displayed Wellmans’ letter and retold the whole story. Reporting on the exhibit, the San Francisco Chronicle published my picture alongside the Grizzly in the Sunday paper. Despite a careful inspection of the skin, though, I never did detect the holes where Wellman shot him.

The multimedia ebook I created for the exhibit, Yosemite: A Storied Landscape, is a free download in Apple Books. It includes the Wellman letter.

ARTISTS AND ARTISANS

Imagining The Ahwahnee

THE AHWAHNEE HOTEL in Yosemite National Park is a radiant monument to Progressive-Era ideas about art and society. The grand hotel’s design, from its massive stone exterior to the geometric patterns embedded in its floors and painted on its walls, reflects a worldview that thrived in the early 20th-century in the San Francisco Bay Area—and in particular at the University of California at Berkeley. Many of those who designed the look and feel of Yosemite’s thoroughfares and buildings had been molded by ideas about public art and architecture incubated in Berkeley classrooms and cafes.

These artists and architects reflected the values of their social set, which included the conservation of nature and a broader acceptance and curiosity toward other cultures. Like-minded colleagues cultivated new concepts in law, biology, and the social sciences that informed policies for managing park visitors and wildlife, particularly after the founding of the National Park Service in 1916 by a group of Berkeley alumni led by Steven Mather. “It was the air everyone breathed,” says Karl Kroeber, who recalls the many social gatherings at the North Berkeley home of his grandfather, the famed Berkeley anthropologist Alfred Kroeber. “In many ways, they saw Yosemite as their park.” Kroeber’s redwood home was designed, naturally, by Bernard Maybeck, himself the grandfather of an architectural tradition that courses through The Ahwahnee’s stone walls, stained glass, and ceiling stencils.

The Ahwahnee’s unique interior was the work of two designers, Arthur Upham Pope, a Berkeley philosophy professor, and Phyllis Ackerman, who was a student in the School of Architecture when they met. The couple married in 1920, and according to a New Yorker profile, they were soon “acting for some of the wealthiest people in the country,” purchasing rugs, tapestry, and pottery.

The Ahwahnee, built in 1927, is their masterpiece. The pair had complete oversight of the decoration, including choice of fabrics, rugs, paint, custom-made wrought iron lighting fixtures, and a wide variety of furniture, much of it custom crafted to their specifications. Taking inspiration from their beloved kelims—they commissioned several for the hotel—and Native American motifs from basket designs, the couple transformed the massive building’s interior into a work of art.

IN RETROSPECT, the Native American influence also reveals some of the tortured racial views afflicting socially progressive Berkeley at the time. California in the 1920s remained a xenophobic place. Although the blatant murder of Native Americans sanctioned in the early years of California statehood had receded, efforts to suppress Indian language and culture persisted, as did the relocation of tribes and villages, including within Yosemite as late as 1969. At the same time, Kroeber and other anthropologists were rushing to document California Indian languages and cultures that were rapidly being assimilated or extinguished. Results of their prodigious efforts, including a large collection of Miwok baskets, are located in the archives of the university’s Hearst Museum.

Jeanette Dyer Spencer, a Berkeley artist that Pope and Ackerman hired to paint the stencils adorning ceilings and walls of the hotel, consulted those archives to create her designs. Her artwork, and the Native American-inspired mosaics of the lobby floor by Henry Temple Howard echoed the geometric Middle Eastern designs that Pope and Ackerman loved. By explicitly associating Native American artisans with those of the ancient world, Ackerman hoped to show them as “creative artists of ingenuity, sensitiveness and dignity.” Meanwhile, Yosemite Indian basket weavers such as Lucy Telles and Maggie Howard were pioneering new designs for baskets just a few miles from The Ahwahnee. The absence of living Native American artists in designing the hotel reflects the painful ironies of the time.

If there is one place that offers a clarifying insight into the ideas and craftsmanship that animated Pope, Ackerman, Howard, Spencer, and their progressive-minded contemporaries in Yosemite and Berkeley, it is the Great Lounge. Since its completion and through its several iterations, guests entering the room for the first time often let out a spontaneous gasp. Set against the grandeur of Yosemite Valley itself, that appreciative gasp signals the enduring achievement of a group of pragmatic idealists who, for a luminous moment, shared an expansive if flawed belief that their public-spirited values, cultural broad-mindedness, and personal artistry could harmoniously combine to create something of beauty. And did.

—Adapted from “Yosemite: A Storied Landscape,” which I created for California Historical Society. A longer version of my Ahwahnee chapter is here. The entire book is free to download on Apple Books.