THEORIES OF ACQUISITION

How could language be?

By Barbara Ramsey

HOW IN THE HELL did a few moderately successful primates ever come up with language? It wouldn’t be credible except for being so commonplace. How, in all its complexity and flexibility, could it have come about?

And I mean exactly that: how could it—not how did it—come about. The “how did” part is explicable. Almost all multicellular organisms manage some kind of communication, even if it’s just a conversation between one body part and another. Peter Godfrey-Smith, an Australian philosopher of science and avid scuba diver, gives the example of a shrimp with long feelers he observed. While feeding, one of the shrimp’s feelers accidentally grazed its mouth. The shrimp began to eat itself and then immediately retracted the feeler. Its nervous system telegraphed “Ouch! Don’t eat this!”

Once vertebrates began to live in the air rather than water, vocalizations traveled easily. Our ancestors chittered, chirped, grunted, and bellowed their way through the world, generating a positive feedback loop of sound-generating and sound-receiving systems that became ever more complex. Evolution’s driver is reproductive success and those creatures whose communication tools promoted more efficient reproduction were favored. Primate groups that hunted cooperatively captured more game and more nutrients.

The “how could” part is more baffling. Perhaps future neuroscientists will discover a mental substrate that enables language to develop. We aren’t simply Skinnerian creatures who are positively reinforced for imitating the sounds around us. I’m convinced of Chomsky’s hypothesis that we possess an innate capacity for language, enabling us to deploy this mighty tool without much effort.

Language systems are composed of a huge variety of sounds, called phonemes, which vary across the world. English has a middling number of phonemes, about forty, while Spanish has only half as many. The Taa language, spoken in Botswana and Namibia, is thought to have almost two hundred. Some languages combine musical tones with spoken syllables. Languages with clicks, unless learned by age thirteen or fourteen, are rarely mastered. And these are just drops in the linguistic ocean.

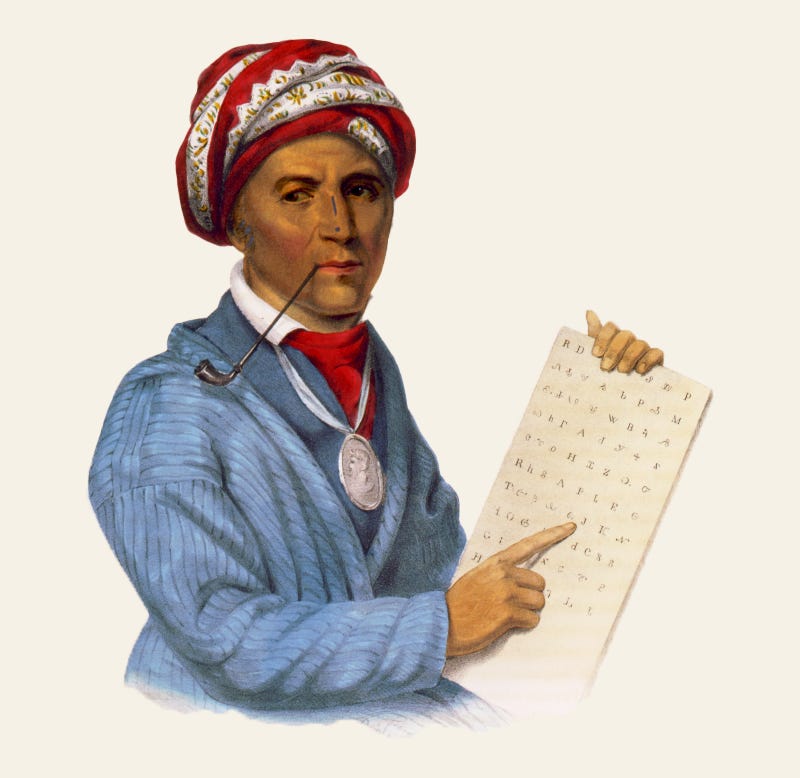

Then there’s written language, at least 5,000 years old and probably older. Still, scholars estimate that only about fifty percent of known languages have a written form today. Nothing in our primate lineage requires us to write, but we do. And we do it a lot. It’s so useful that people without a written language can adopt one quickly. The Cherokee leader Sequoyah invented a written form of Cherokee over a twelve-year period and it remains in use today.

Sequoyah was monolingual in Cherokee. He knew English speakers had a visual representation of their language, but he was unable to speak, read, or write it. He began to create his own writing system in 1809 by carefully analyzing the Cherokee language spoken all around him. He composed a syllabary—in which written symbols represent whole syllables—rather an alphabet, supporting the evidence that he didn’t use English as a template. His whole story resembles a fairy tale. By some accounts, a group of tribal members even suspected he was sending messages through witchcraft, not marks on paper. Ultimately, his written form of Cherokee spread quickly and was formally adopted by the tribe in 1825. And sure, the guy who came up with it was a genius, no doubt. But once he’d figured out the basics, he taught it to his six-year-old daughter, A-Yo-Ka, who helped him finish the syllabary. This tells me that we’re wired not only to speak language, but to convert it into visual symbols if given the slightest encouragement.

Knowing this comforts me, especially when I feel compelled to finish this little essay rather than all my unanswered emails, unsewn quilts, and unfinished taxes. I’m only a primate, after all, one driven to speak and to write by a brain beyond my control.

Writing in beauty

By Barbara Ramsey

REBECCA WILD’S CALLIGRAPHY class could have been an ordinary one: bakers who needed more legible cakes, artsy college students wanting to improve their handwriting, tattoo artists perfecting their Gothic script. But Rebecca was an extraordinary calligraphy teacher and one day in 2009 she met someone even more extraordinary.

Ibrahima Barry was a slight, soft-spoken African man in his early thirties with an accent that required close listening. Rebecca learned that he wanted to improve his script, but she had no idea what script and no inkling of the long road that had led him to her class. That road had begun almost two decades earlier in a Fulani neighborhood in Guinea, West Africa.

When Ibrahima was fourteen and his brother Abdulaye was ten, they came to their father with a problem. They were having trouble learning to write.

For hundreds of years, the Fulani people had traveled, traded, and extended their range over much of West Africa. By the time the Barry brothers were growing up, the Fulani numbered about forty million and had significant populations in Guinea, Nigeria, Senegal, Cameroon, and Mali. But their language (known as Fula, Fulbe, or Peul) had no written script of its own. This is common. Of the world’s approximately 7,000 languages, only about half have a written form.

Their language could be approximated by Arab script or the Latin script brought by the French, but both failed to capture some of its sounds. Many literate Fulani didn’t understand the writing of people from other regions. There was no nation state to create a standardized language curriculum or a single writing system. By the end of the 1980’s, less than twenty percent of the Fulani could read, which meant the language could disappear in a few generations.

Ibrahima and Abdulaye’s father was well-versed in the Arabic version of Fula. People often sought his help in reading letters from their relatives in far-flung parts of West Africa. He’d become adept at deciphering and “best-guessing” the meanings of these letters. But the boys were frustrated with such guessing and felt it was holding them back. Why not create a written alphabet specifically for their own language?

“Many famous people have tried”, he told them. “But none have succeeded.” The boys were too young to understand that creating a flexible alphabet capable of representing all the specific sounds of a language is unimaginably difficult. When they insisted, their father smiled and wished them well.

And what pair of young kids doesn’t dream of creating a code? The boys labored over it after school, trying out new shapes and figuring out which shape most “looked like” the sound they wanted to represent. After six months of work, they showed their dad their twenty-seven letters (eventually twenty-eight), read from right to left like Arabic. He thought maybe they were just messing around, drawing squiggles.

Nonetheless, he contacted an educated relative who worked for the government to evaluate the boys’ claims. The man put the boys in different rooms so they couldn’t secretly signal each other. He dictated a different word or phrase to each one individually and had him write it down. He then had each boy read the other’s writing and tell him what was on the paper. They passed the test without difficulty. “I think these boys are on to something,” he told their dad.

But would it work in practice? The boys taught their script to their sister, Aissata, who quickly mastered it. They taught it to their friends and their friends’ friends. Adults were keen to learn, especially the Fulani merchants who needed transaction records and the market women who wanted to avoid being cheated. Abdulaye began painstakingly translating school books from Arabic script as well as books requested by friends and neighbors. He and Ibrahima set up an informal classroom in their father’s shop to teach people to read them.

But the brothers wanted more. In 2000, when Ibrahima went to the university in Conakry, Guinea’s capital, he spread the word. He taught the new script to other university students and found teachers eager to add the alphabet to their curriculum. He and his friends wrote new books about how to dig wells, purify water, and use basic math.

This new alphabet needed a name. The word “alphabet” comes from the Greek words for the first two letters, alpha and beta. The teachers suggested the Barrys call their script “ADLaM” after its first four letters— A,D,L, and M. The teachers also helped disseminate ADLaM to schools and learning centers in Guinea, Nigeria, Togo, Senegal, Liberia, and Benin. They created an acronym to remember the name: Alkule Dandayde Lenol Mulugol. It means “the alphabet that protects the people from vanishing.”

Though the Fulani people were enthusiastic, the government in Conakry wasn’t so sure. When Ibrahima started a student newspaper and became president of a group of reform-minded university students, the government branded him a troublemaker and put him in prison for three months. When released, he left for Senegal.

Almost a third of Senegalese are Fula speakers, and word of ADLaM had already spread through the country. One day in a Dakar market, a woman heard him speak Fula. She showed him a book—one he’d written while in Conakry—and asked if he could read it. “Well…maybe, just a little,” he said. A friend of hers, a Fulani from Guinea who sold palm oil, had brought the book to the market and was holding classes to teach the script to other Fulani women.

The brothers knew that ADLaM needed to be computerized. Wanting more education in English and hoping to create a digitized version of the script, Abdulaye moved to the United States, eventually settling in Portland. There, he learned about a UNESCO project that supported the development of linguistic tools for global information networks. UNESCO referred him to a linguist at UC Berkeley. He wrote to her but never heard back.

After Ibrahima joined his brother in 2007, they contacted a software company in Seattle about the project, but the firm demanded a hefty price. To pay it, the brothers took additional jobs and saved money for a year, but the resulting typeface was disappointing. Ibrahima and Abdulaye didn’t find it beautiful enough.

Navajo people speak of “walking in beauty”. The Fulani are the same. The women are famous for engraved gourds, beading, and weaving. Both sexes are known for elaborate body adornment and tattoos. Their headgear is carefully crafted and often decorated with intricate geometric motifs.

And so it was that Ibrahima began Rebecca Wild’s calligraphy class—to learn how to make a more beautiful typeface. She was impressed by his lettering but she’d never before seen such an alphabet. Because the Fulani revere modesty, it took Rebecca another week to learn that he and his brother had invented it. She felt compelled to help.

While working with Ibrahima on the script, Rebecca contacted a friend who arranged for him to attend a local calligraphy conference held at Reed College. Organizers were so impressed that they brought both brothers to Colorado the next year to present to a national conference. For their talk, the brothers invited members of the Fulani community who spoke to the personal and cultural significance of this new way of writing.

The computer scientists and linguists at the Colorado conference included the one from Berkeley who Abdulaye had tried to contact ten years earlier. The brothers met representatives from Google and Microsoft. And they met an editor from Unicode—the text encoding standard for the world’s major writing systems on the internet. From there, things moved quickly. Unicode certified ADLaM in its 2016 release of approved text standards and it became generally available in the 2019 Windows update. There are now multiple ADLaM typefaces. Ibrahima named one of them “Rebecca”.

Note: The full story of ADLaM is much richer than my summary can convey. To hear the Barry Brothers tell their own story in their own words, watch a talk they gave at Google.

FOR THE LOVE OF TYPE

THESE LETTERS are typographic artworks based on the ADLaM Display font commissioned by Microsoft and designed by Neil Patel, Mark Jamra, and Andrew Footit. They were inspired by the spots, lozenges, and chevron patterns found in traditional textiles of the Fulani culture.

ON LANGUAGE

Swahili-Hawaiian Punch

A SONG ON YOUTUBE recently caught my imagination, one with a mainstream Christian message sung with an old-fashioned country twang by a cowboy. In Swahili. The Kenyan singer had a ten-gallon hat and a great set of pipes. With its Swahili lyrics, the Christian message went right past me (thankfully), but the gospel lilt came through loud and clear. And I love gospel.

It gets weirder. I listened to the song repeatedly and began to wonder: is this really Swahili? I swear it sounds Hawaiian.

I know virtually nothing of either language. I’ve been thrilled by the Hawaiian people’s successful struggle to bring their language back from the brink of obliteration. I have listened to many kinds of Hawaiian music, and have heard spoken Hawaiian in several different settings. That’s pretty much it.

My ignorance of Swahili is even greater. It’s limited to my vague familiarity with the Swahili version of the African National Congress anthem, called Mungu Ibariki Afrika. The lyrics are beautiful and the tune makes you want to sing along, unlike a certain other national anthem I know.

I checked into it and there’s no doubt the cowboy song is in Swahili. But as I listened, the similarity to Hawaiian in phonation—the sounds—became clearer. When I searched for confirmation, Google flat out rebuffed my idea. “There are no historical, grammatical or syntactical similarities between the two languages,” it scolded.

So I turned to ChatGPT. An old friend once called me an “early resistor” of technology, but Kerry got a subscription to ChatGPT when it first came out and I’ve started to use it. From time to time. Every day.

I appealed to ChatGPT to soothe my feelings over Google’s reprimand. I asked it to focus on phonological resemblances, ignoring history, grammar, and syntax. I asked specifically about the features I’d noticed: the high vowel-to-consonant ratios and an ample supply of short, repetitive syllables.

The dissertation I received (in 23 seconds, mind you) was heartwarming. Yes, it told me, Hawaiian and Swahili share an entire world of sound similarities. Both languages favor simple syllables like "ba," "ka," or "ma," making them rhythmic and easy to pronounce. For example:

Swahili: rafiki (friend), safari (journey)

Hawaiian: aloha (love, hello), ohana (family)

Both use repetition for emphasis (linguists call it “reduplication”). Hawaiians say wikiwiki for "quickly" and the Swahili say polepole for "slowly." Both avoid consonant clusters. In fact, Hawaiian disallows certain complex consonant clusters, those horrible vowel-less throat sounds that can make Polish impossible to pronounce.

And then I read, “The phonetic simplicity and high vowel ratio in both languages make them particularly accessible for non-native speakers and ideal for music. This is why both Swahili and Hawaiian songs often have a global appeal.” Hallelujah! Turns out the auditory features I’d perceived reinforce both the rhythm and melody of sung language.

Now I’m hoping my new favorite Kenyan, Maombi Samson, will spark a novel cultural trend: singing cowboys bilingual in Swahili and Hawaiian. It could go global! —Barbara Ramsey

Words we love… and hate

By Barbara Ramsey

MY UNCLE ED was driving my mother and me along an Alabama country road near her home when she pointed out what looked like a large puddle to our right. “Mr. Grimes sure can catch some good catfish in that pond,” she declared.

“What?” I was incredulous. “That can’t be more than three inches deep!” I looked over at Uncle Ed, an experienced Southern fisherman who could occasionally reason with his sister.

He paused, and then spoke in a low drawl, “Well, if there are catfish in that pond, they sure must have to hunker down.”

End of argument. Uncle Ed was a country lawyer with a great gift for language. “Hunker down” settled it.

When words like “hunker” come out of nowhere, they thrill me. I’m also fascinated by words with a close resemblance that people confuse and misuse.

Take disinterested and uninterested. Disinterested means “not biased” or “without selfish motive”. Uninterested simply means “not interested.” Many use them interchangeably to mean “not interested”. British writer Anthony Burgess labeled this “one of the worst of all American solecisms—it makes me boil.” Note the phrase “one of the worst.” Mr. Burgess had other bones to pick—bones that lie on the battlefield where Brits and Americans fight over words, spelling, pronunciation, and football vs. soccer.

But sometimes the enemy is us. My sister Pat is infuriated by people confusing enormous and enormity. Enormous is an adjective meaning very large. Enormity is a noun meaning “an act of extreme evil” as in “Hitler’s enormities shocked the world”. Over time, enormity has acquired a less pejorative connotation and can be simply “an act of very great size or importance.” Such word drift is a small matter to some people but to my sister it is an enormity.

Some word pair bewilderments bewilder me. I’ve never had trouble with the adverse and averse adjectives. Adverse means bad. Averse means to be ill-disposed to. A single “D” explains my adverse reaction to that guy I’m averse to.

Likewise insure and ensure, where there’s not so much as a “D” to help us out. Despite their similarity, insure and ensure seem quite distinct. Insure: to protect against a negative outcome. Ensure: to make certain. Quite separate in my mind.

Speaking of confusion, I was raised in a place where the soft “i” and soft “e” were pronounced almost identically. I say the words “pen” and “pin” the same way. They aren’t confused in my mind, but I have asked for a writing implement and received an object that pricked my finger.

One word pair that often throws me is affect and effect. In speech, the difference in voicing those initial vowels can be so subtle as to be non-existent, so I can use the wrong one and sound like I’m using the right one. But in writing? I am often perplexed. According to the dictionary, affect is a verb that means to impact in some way, whether that impact is negative or positive. Effect is also a verb but means to get a specific thing done and implies intention.

For example, “U.S. foreign policy almost always affects things in the world but rarely effects those things it desires.” If only I could memorize this example and make it stick! What’s worse is that affect and effect can both be nouns as well as verbs. Affect is usually a verb and effect is usually a noun, but this assumption is incorrect often enough to make me dizzy.

Possibly my favorite of these word pairs is confuse and conflate. I love that both words describe the awkward way they’re misused. Confuse means to mistake one thing for another. Conflate means to merge two things together, often in error. When a mix-up occurs, these separate meanings get conflated, which creates—you got it—confusion. Such an occurrence defines yet another word: irony.

EVOLUTION

Two knights and a lady: an origin story

If European languages share a common ancestor, who was that ancestor? Born three centuries apart, two men and one determined woman were key to finding an answer.

By Barbara Ramsey

OUR FIRST KNIGHT, Sir William Jones, was of born in 1746 to a family of Welch scholars. He became one himself at Oxford, where he was known for his erudition in the study of languages, history, and law. Interested in politics, he also ran unsuccessfully for parliament and helped Benjamin Franklin agitate for American freedom in Paris. In 1783, he was sent to India to take up a position as a judge on the British Supreme Court of Calcutta.

Once there, Jones studied Hindu astronomy and the ancient legal system of pre-Islamic India. Always fascinated by languages, he also studied Sanskrit, analyzing the Vedas with Indian pundits. And in 1786, he became convinced that Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit—three of the eight languages he’d become fluent in—had all sprung from a common source. Others had seen these connections, but Sir William was the first to create widespread interest in the source of this protolanguage. Where was it spoken? Who were its speakers?

This is mind-blowing to me. An agent of the British Empire in the 1780s promulgated the idea that Europeans and Indians shared a root language? I did not see that coming.

Fast forward about 150 years to our next scholar, Marija Gimbutas. Born in Lithuania to doctor-parents in 1921, she grew up among the intelligentsia, surrounded by writers and musicians. At university, Gimbutas married and had her first daughter while studying linguistics, archeology, and ethnology. But war interfered. In 1943 she carried “her thesis under one arm and her baby under the other” as she fled the invading Soviets.

In 1950, after postdoc work in Europe, Gimbutas was invited to Harvard as a lecturer in anthropology and a Fellow of the Peabody Museum. Sounds pretty great, right? But Harvard was less than hospitable to women and refugees, she later recounted. She was given an “office” in a small room in the basement and no salary for the first several years there. How’s that for Ivy-League collegiality?

Of course that didn’t stop her. In 1963, UCLA hired—and paid—her as a Professor of European Archeology. Over the following years, Gimbutas directed major excavations throughout Greece and Macedonia and began to synthesize a number of new ideas about early European history. In particular, one ancient culture fascinated her. She called them Kurgans, after the Russian word for burial mound, because they often buried their dead in pit graves topped by earthen mounds.

The Kurgans were horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who lived about five thousand years ago on the western steppes north of the Black Sea. They herded sheep, goats, and cattle at a time when many people in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia were becoming sedentary agriculturalists. Kurgans were among the first to develop the wheel and used two-wheeled carts and four-wheeled wagons—some were even buried with them.

Kurgans had a high protein diet, unlike the agriculturalists of their time. The ate their herd animals and also drank their milk—archeologists have found milk by-products on the teeth of both adults and children. (Thank god they didn’t have dentists or we might not know this.) And because they herded on horseback, they could manage three times as many sheep as pedestrian shepherds.

The grass-covered steppes were inhospitable to farming, but mounted pastoralism transformed them into a vast food resource. The Kurgans converted a caloric desert into a kind of Neolithic Diary Queen, enabling them to enlarge their population. Gimbutas was aware of evidence that they had spread from their ancestral homeland into western Europe, but there was a great deal of argument about whether this spread was peaceful or violent. She came down firmly on the side of war. Gimbutas envisioned Kurgans as a mounted, armed people who introduced a whole new language called Proto-Indo-European (PIE), mainly through migration and conquest.

Earlier scholars had analyzed the similarities among Indo-European languages, from the Celtic languages of the British Isles to the Indic languages of Bangladesh. Time and again, they found similar nouns and verb forms that were absent from the languages of Africa, the Americas, eastern Asia, and the Pacific. Gimbutas believed the Kurgans were the key to the mystery of the origins of Proto-Indo-European and she had the archeological chops to support her claim.

But Gimbutas was also a controversial figure. She posited that matriarchal societies had predominated prior to the Kurgan invasions, a theory that was popularized by second-wave feminists in the 1970s. With debatable evidence to support this idea, some scholars cast doubt on her work.

Enter the second knight of our story, Lord Colin Renfrew. Still alive today at age 87, he was born into British nobility and educated at Cambridge (not Massachusetts, as he likes to point out). Well known as an archeologist and paleolinguist, he worked with Gimbutas on a number of archeological sites and they had a long-standing collegial relationship. But they strongly disagreed about the origins of PIE speakers.

Renfrew believed that PIE originated in Anatolia, not north of the Black Sea, and was first spoken by agricultural peoples. He also believed that the PIE languages spread by diffusion, not migration, and was largely peaceful. For more than forty years, he promulgated these theories, persuading many other scholars. And there was a lot of evidence to support his views, at least until paleo-genetics—the study of the DNA in skeletal remains of prehistoric people—came along.

The Kurgans are now considered part of a larger group of mounted pastoralists called the Yamanaya, whose DNA, obtained from burial mounds, has been studied and compared to both other prehistoric cultural groups and present-day human groups. As it turns out, many living Europeans, especially northern Europeans, share a significant proportion of their genes with the Yamnaya, and relatively little with the ancient agriculturalists in the rest of Europe. For example, the Neolithic farmers who built Stonehenge contribute very little to the genetic make-up of most English people. Steppe-herder genes predominate.

Of the many curious twists and turns to the Yamnaya DNA story, I find one especially intriguing. We now know that the risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) is increased by certain genetic markers, especially among people of European descent. These genetic markers are first found in the archeological record in Yamnaya remains. Why would that be?

These specific genes are part of our immunological response system, which goes a bit haywire in MS, causing the body to attack its own nerve cells. But these genes also become active in people infected with the anthrax bacteria. Remember anthrax? The germ terrorists put into envelopes? Well, in the natural world, anthrax frequently infects grazing herbivores such as sheep, the same ones that the Kurgan/Yamnaya herded. The MS genes were adaptive, protecting the animal herders.

Gimbutas died in 1994, too soon to have been cheered by the support of paleogenetics. But there is now a yearly memorial lecture given in her honor at the University of Chicago. In 2020, the lecture was given by Lord Colin Renfrew, who was there to acknowledge that Marija Gimbutas had been right all along.

Taking umbrage

By Barbara Ramsey

I LOVE THE word “umbrage”. The first time I ever used it (albeit just in my head, not out loud), I was working out by myself in an exercise studio one evening when another woman came into the room and started her routine. I’d seen her around the studio several times but had never had a conversation with her, just hello and good-bye. I tried to start up some small talk and asked her if she’d had a good day. “Well,” she sniffed, “Whatever kind of day I’ve had, it certainly isn’t any of your business.” All of a sudden it seized me: She was taking umbrage at my remark! She was an umbrage taker!

The literal meaning of the word is offense or annoyance, as in “He took umbrage at her impudence.” And although being offended is a hallmark of the human, we have surprisingly few words for it. Besides offense and umbrage, there are no other one-word synonyms that come very close. “Annoyance” isn’t good. It’s too general, too vague. “Irritation” is worse. I once heard a biologist say that “Irritation is the hallmark of cellular life. If you can irritate it, then it’s alive”.

We need more specific ways to describe this all-too-human sensation. “Personal displeasure” is awfully good. It conveys the feeling that whatever the offending matter, it’s coming in close, getting personal. I also like “sense of injury” as it contains the idea that one doesn’t actually need to be injured, one can merely perceive injury. This is crucial. The person being offended is the judge here. Unlike an injury that can be detected with an x-ray, offense is a subjective matter.

Like all subjective matters, disagreements arise. What causes me to take umbrage may strike you as amusing. For those who crave the blood sport of being offended, taking umbrage can create a thrill of self-righteousness. For others, being offended is an energy drain to be avoided.

There’s another curious thing about both umbrage and offense. The verbs that go with them are “give” and “take.” We give umbrage and we take umbrage. The “give” part seems plain enough but what about the “take”? Aha! This is where it gets interesting. “Take” can be defined as “to get into one’s possession by voluntary action.” Note the voluntary part. For some, taking umbrage doesn’t feel like a voluntary action at all. They may be taking it automatically without their volition. For others, umbrage may be lying around but they don’t feel the desire to take it. They’re perfectly happy to leave it lie.

The first use of umbrage in the fully modern sense is found in the early 17th century where it was used to mean the “suspicion that one has been slighted”. Again there’s the subjective sense, where “suspicion” clearly implies an unstable type of perception. Suspicions are sometimes well founded and other times mere paranoia. When we take umbrage, we may be basing our sense of offense on a perception that’s not entirely trustworthy.

What about etymology? What is the root origin of this word? “Umbrage” is thought to have entered the English language sometime in the early 15th century from the French word ombrage, meaning shade or shadow. Deeper origins are in the Latin umbraticum, “of or pertaining to shade.” The root of umbrage links it to words such as umber (a color like ochre but darker = a shade of ocher), umbrella (a canopy of cloth that creates shade and protects against sun or rain), and penumbra (the partially shaded outer region of a shadow; the shadow cast by the earth or moon over an area experiencing a partial eclipse).

Which brings me to a curiously modern phrase, “to throw shade,” meaning to criticize someone, to hold them up to ridicule. Sounds awfully much like giving umbrage to me! Imagine that—a relatively obscure word from a Latin root given to English via French in the early 15th century somehow jumps up into the mouths of 21st century kids speaking the latest vernacular. Makes me happy.

Why we (mostly) don’t speak Celtic or French

By Barbara Ramsey

“ENGLISH IS CLASSIFIED as a Germanic language? What about all the words from French and Latin?” Kerry was genuinely astonished.

I’m obsessed with language origins and had learned that English is considered a Germanic language, along with Dutch, German, and Flemish. I was surprised that my well-educated husband didn’t share this understanding. Unlike me, he had studied German in college. And I know that English has tons of French words. I suddenly wanted to review my linguistic beliefs.

A quick internet dive uncovered some amazing facts. Approximately sixty percent of all English words are derived from French and Latin, while only about twenty-five percent have Germanic roots. But get this: according to the billion-word database maintained by Oxford University Press, ninety-eight of the one-hundred most commonly used words in English have Germanic origins. The two that don’t? “People” and “cause”.

Many of the earliest recorded languages of Great Britain are Celtic, similar to those of contemporary Cornish, Welsh, and Breton speakers. But in 40 AD, England was invaded by the Romans, who spoke Latin. Unlike Celtic, Latin is a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language, introduced by a herding people from the Eurasian steppes (see my article, “Two knights and a lady: an origin story”).

Latin did take hold all over much of Europe, ultimately morphing into French, Spanish, Italian and the rest of the Roman-inflected—hence “Romance”—languages. But although the Romans occupied Great Britain for four hundred years, there’s almost no linguistic trace of Roman Latin in English. How could that be?

More invasions.

Starting in the fifth century, less than two generations after the Romans left Britain, the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians arrived from mainland Europe. These Germanic peoples slowly but surely altered the linguistic landscape. Most of England began to speak a very different tongue, now called Old English. It reigned supreme until 1066 AD.

How did the language of the Anglo-Saxon invaders supplant those of the Romans and Celts? Did they simply move in, kill as many of the natives as possible, and replace them? Gee, sure sounds like a familiar scenario. And while it was a plausible theory for a long time, recent genetic evidence shows that’s not what happened.

Those Britons in the far west that kept speaking Celtic until the 19th century were genetically almost identical to those on the rest of the island who hadn’t spoken Celtic for more than a thousand years. It’s now hypothesized that the conquering Germanic speakers simply found good farmland, married into the local population, and settled down. Since they functioned in many places as overlords, learning their language probably became extremely useful to those natives who wanted political or economic power.

Though the Celtic language got sidelined, it probably remained the mother tongue for most people for many generations, while the Anglo-Saxon tongues merged and change in subtle ways. The vocabulary remained essentially Germanic but the sentence structure became slightly more Celtic.*

The biggest gift the Celts gave us, in my opinion, was the elimination of Latin and Germanic cases. A case is a grammatical category that indicates the function of nouns and pronouns. Cases are why Latin and German nouns are a huge headache for adult language learners. The Celts apparently weren’t gonna play that game. Their kids learned the new language but jettisoned the clunky bits.

The Normans, those French-speaking descendants of Vikings, invaded England in 1066 AD. Like the Germanic tribes before them, they were strong enough to rule over the Brits but not numerous enough to push them out. The Normans established a ruling aristocracy at lightning speed and French became the language of the bosses—but not of the people. The English commoners adopted only those parts that suited them. “Pig” is German. “Pork” is French. Need I say more?

So our Latin-inflected words come via the French, not the Romans. We rejected the French method for constructing sentences, retaining what is essentially a Germanic syntax with Celtic influences. And after nearly 300 years of being the official language of England, the English legal system jettisoned French in 1362. English was back and the words of Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Bob Dylan were yet to come.

If German is our cake, French is the icing. In certain disciplines, there’s a lot of icing. Ninety percent of our technological and scientific words come from French or Latin. But if you’re shooting the breeze with your friends du sprichst Deutsch.

*For a detailed look at what bits of Celtic remain, John McWhorter’s Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue is excellent.

Playing with dingalings

By Barbara Ramsey

AS A LOVER of language, I was delighted to see a recent article in the New Yorker about a man named Ganesh Devy. Mr. Devy has undertaken the truly gargantuan task of surveying the over 120 languages spoken by India’s billion and a half people.

Delighted, that is, until I read this:

Indians, for example, share a fondness for “echo words,” such as puli-guli in Tamil, where puli refers to tigers and guli is a rhyming nonsense term meaning “and the like.” This quirk occurs in South Asian languages from at least three different families but perhaps in no other language anywhere in the world.

What the hell? I’d always believed the New Yorker’s fact checkers were the very best. How could such claptrap pass muster? Claptrap, by the way, is a rhyming English noun meaning “absurd or nonsensical ideas.” Its first recorded use was in 1730 as a stage term meaning a trick to generate applause. And guess what? The word appeared later in the very same issue of the New Yorker when a different author wrote about a person who “seems to have believed in this claptrap”.

We use rhyming compounds, the common descriptor for such words in English, to describe everything from a genre of music (boogie-woogie) to the old and clueless (fuddy-duddy) to a trivial trinket (knickknack). Granted, the writer’s use of the term “echo words” is a lovely improvement over the more pedantic “rhyming compounds.” But the magazine’s ignorance of echo words in English appalled me.

In fact, six months earlier, my sister Pat and I had compiled a long list of such words. She and I share an interest in neologisms and out-of-the-way words of various kinds, so this echo-y tangent was just another day in our shared obsession. And now I planned to use that list to insure the magazine’s boo-boo would not go unchallenged. I wrote the following letter to the editor:

If you artsy-fartsy East Coast riffraff claim to be fact-checking, I suggest you rethink your loosy-goosy assertion that, except for South Asian languages, “perhaps no other language anywhere in the world” has echo words. Maybe your tighty whiteys are cutting off the circulation to your brain? In future, don’t be such dingalings.

I doubt they’ll print the letter, but writing it cheered me up, particularly since it enabled me to deploy our list of echo words. My sister and I love to take such linguistic joy rides together and the English language affords a wealth of opportunities. My native tongue, which is the only one I speak, contains words from languages as diverse as Algonquin (skunk), Mandarin (tycoon), and Old Norse (beaker). And I do believe English needs a few extra echo words. I’m envious of that “puli-guli” term for tigers and the like. How about “scary-hairy” for grizzly bears and the like?

Shoddy Excuses

By Barbara Ramsey

HERE’S A PHRASE we all hate to hear: “With all due respect…” Which means you will soon be disrespected to the max. The key word is “due” and not “respect”. “Due” signals a verbal punch to the solar plexus.

The phrase is supposed to work like a get-out-of-jail-free card. The speaker thinks, “No one can accuse me of disrespect!” Oh yeah? Yes, we can. No one ever says, “With all due respect, I absolutely love your shoes”.

The phrase is the identical twin of “No offense intended, but...” The “but” reveals everything. Offense is not only intended but eagerly anticipated. Preemptive rationalizations like these are employed to obscure the fact that the speakers know exactly what they’re doing. They merely wish to be absolved of their sins immediately prior to committing them. You want absolution? Take that up with your priest or pastor or rabbi or mom.

Don’t get me wrong. I believe in giving offense when needed. Some people deserve—maybe even require—a dressing down. Facing up to a bully or challenging someone who’s in the wrong? Go for it, honey! Just don’t pretend the situation is anything other than it is. And first ask yourself exactly what you’re trying to accomplish.

My friend Steve is a playwright. He once wrote a comedy, The Fun in Funeral, with an obnoxious character who regularly butts into other people’s business. Steve gave the character a line that I love: “Can I say something helpful about your personality?”

The “all due respect” or “no offense” speakers are usually doing exactly that. They’re trying to tell you something helpful about your personality. And that rarely goes well. Preemptive rationalizers are often the same people who believe that the words “brutal” and “honesty” go together. They don’t! Brutality goes with cruelty, it goes with meanness, and it goes with dishonesty. Honesty is difficult exactly because it requires gentleness, humility, and kindness. I suggest trying those things instead.