Who's crazy now?

The doctor discovers what's real. Southeast Kansas discovers hippies. The 19th century discovers cephalopods. And a rare bird alights. Plus: Snippets on Mark Rothko and Adam Smith.

BIRDS

In honor of my friends Paul and Pat, who are in Hawaii for the month, I’m recounting a trip a few years ago to see rare and endangered birds in Kauai.

THE ROAD TO ALAKA’I has potholes the depth of wheels. The Alaka’i Swamp, the last refuge of Kauai’s native birds, is a plateau adjacent to Mt. Wai’ale’ale, which averages 373 inches of rain per year. The area is too elevated and cold for mosquitoes, which arrived in the watery hulls of trading boats. They brought a malaria deadly to the birds. Of the eight endemic species left, two were declared extinct six years ago. I’d be lucky to see one.

The trail begins with tree shrubs stunted by the porous alkaline soil before giving way to a large forest. At its edge I saw a scarlet bird, an Apapane, feasting on a flowering tree. From fifty feet away I got off a few shots and counted myself fortunate. But for the next couple of hours, nothing, until an I’iwi suddenly appeared on a branch a few yards away. The Hawaiian nobility famously prized the feathers of this scarlet honeycreeper for their royal coats and helmets, and the birds often appeared in island myth and songs. The I’iwi sat for several minutes while I photographed him and thought to myself, “Mahalo.”

TALES FROM THE CLINIC

The sponge count

By Barbara Ramsey

LET US CALL HIM Mr. Jones. I had worked as a family practitioner in a small East Oakland clinic for less than a year when he arrived as my first patient of the afternoon. Jones had never been seen at our clinic before and his chart was blank except for name and date of birth. He’d been scheduled for a half hour visit.

A wizened guy in his 60’s, he looked at me suspiciously as he began to recount his story. He’d been having “stomach trouble” for several years and doctors hadn’t been able to help him. He launched into a lengthy story of his various interactions with doctors. Some of the story was clear enough—stones in his gallbladder and a surgery, maybe last year, that was supposed to remove them. Other parts of his tale didn’t quite make sense or seemed outright nutty. People were out to get him. There were things inside his body that weren’t supposed to be there.

Once I’d gotten as much info about his abdominal difficulties as I could, I took the rest of his medical history. He’d broken his arm in his 20’s. Once he’d had pneumonia. And yes, he drank every day and sometimes passed out. No, he wasn’t bothered by that. His drinking wasn’t the problem. His drinking made his problems tolerable.

By the time I’d finished his history, we’d been in the room for forty-five minutes and I had two patients waiting. I apologized for not having time to conduct his physical exam and encouraged him to return in ten days for a follow-up visit. I’d do the physical and we’d proceed from there. He continued to eye me with suspicion but agreed to return.

I WASN’T SURE HE WOULD. And I wasn’t sure I could do him any good. He was a long-term alcoholic, possibly with a psychiatric disorder that caused paranoia or even delusions. Perhaps there wasn’t a separate psych problem and he suffered from brain damage associated with alcoholism. Neurological impairment can lead to memory loss and people make up stories to compensate. His medical problems might not be solvable by the likes of me.

He did return in ten days, right on schedule. Starting at his head, I examined his eyes, ears, nose, throat, neck, lungs, and heart, finding nothing remarkable except a slightly rapid heartbeat. Then I got to his abdomen. Sure enough, there was a scar from his gallbladder removal. I was familiar with such scars from patients who’d had the good old-fashioned abdominal surgeries common before laparoscopic procedures became the norm. But this scar wasn’t normal. It was chronically inflamed, thickened and red, with open, weeping lesions.

I asked if his procedure had really been done more than six months ago. The scar looked fierce and recent. I tried to palpate his belly with my hands, but his abdomen wasn’t just tender, it was exquisitely tender and abnormally distended. I was freaked out. Mr. Jones might have neurological problems, all right, but those were the least of his worries. He got dressed again and I discussed my findings.

“Yes,” I said, “Of course you’re having belly pain. You have something very wrong going on, a dangerous medical problem. You should go to the emergency room for an evaluation today.” I wanted him admitted to the hospital immediately.

He explained, calmly, that he would do no such thing. Those doctors at the hospital had made him worse by doing their infernal surgery. He wasn’t going to give them another chance to hurt him. “Oh yes, those doctors want me to come back. I know that,” he said. But he wasn’t going.

I was accustomed to patients resisting instructions or treatments. There’s a certain dance, a give and take that’s required. But this was different. I knew when I was meeting a wall and this guy was a wall. Ultimately, he did agree to come back the next day for further discussion. That was as good as I could do. I had some blood drawn for testing and told him I’d be talking to other doctors prior to his next visit.

Immediately after he left, I called the hospital where he’d had his gallbladder removed. It was a good hospital with a mission to care for everyone who walked through the door. Against the odds, I got through to the surgery department immediately and—either accidentally or providentially—got their best guy. He was relatively young, up and coming. He performed more surgeries per week than anyone else on staff. Indeed, he’d performed the surgery on Mr. Jones.

I still remember the sound of his excited voice. “Jones? Mr. Beaumont Jones? You’ve seen him? He’s alive?” He sounded both incredulous and overjoyed. I told him what I knew. He explained that yes, Mr. Jones had his gallbladder removed seven months earlier. The surgeon had seen him several times after the surgery, but no, Mr. Jones didn’t heal as expected. His post-op course was what you’d expect only if you expected the worst.

Surgeons are responsible for everything that happens during an operation, but they rely on many others to help. There’s always someone—a surgical tech or a nurse—who performs what’s called a sponge count. A “sponge” is a piece of gauze. The person who does the sponge count keeps track of exactly how many sponges there are at the beginning of a procedure and how many at the end. A sponge count can be wrong, but it’s rare. For those rare cases, every piece of gauze has a tiny string woven in that shows up on an x-ray. When the surgeon ordered an abdominal x-ray, there it was, a tiny string.

But Mr. Jones had walked out of the hospital after the x-ray and never returned. The surgeon called but couldn’t reach him at his house. He sent letters explaining the situation and asking Mr. Jones to please come back to the hospital. No response. Then Mr. Jones apparently moved to another residence, and no one knew where. The surgeon feared for Mr. Jones’ life but couldn't figure out what else to do.

Turns out Mr. Jones did receive those letters from the hospital and read every one. He knew there was something inside him that shouldn’t be there and had tried to tell me that on his first visit. But he didn’t want to return to the place where they’d left something inside him, even if it endangered his life.

I couldn’t fault the guy’s logic, but I had to persuade him to speak to the surgeon. When he saw me the following day, we had a long discussion. I got the surgeon on the phone and the two of them talked. I believe there was something in the surgeon’s voice. I’d heard it, too—the joy of finding Mr. Jones alive—that ultimately turned the tide. Mr. Jones agreed to go back to the hospital.

A follow-up surgery was scheduled, but I worried Mr. Beaumont Jones might change his mind again. He’d given us his new address and the surgeon sent a social worker to check in with him a couple of days before the repeat surgery. I also decided that this was a rare case where a house call from Dr. Ramsey was warranted.

I made a date to go to his house the day before the surgery. When clinic was over for the day, I drove to his home, a big old Victorian built in the day when this part of Oakland had been orchards and farms, long ago. The ramshackle and decaying house had been converted to a group home with a landlady who acted as a gatekeeper. Most residents were single men receiving some kind of assistance or disability payments to pay their rent.

Mr. Jones met me on the ground floor in a living room that was the shared space for visitors and family. He was reserved, reluctant, and resigned. I tried to be as encouraging as I could. “You’re going to feel so much better once this is done!” I said. “In another two months you’ll feel like a new person.” I knew I sounded way too chipper. Still, he promised to be at the hospital the next day, rain or shine.

And he kept his promise.

PERSONAL HISTORY

When counterculture came to the Bible Belt

THE HOBBIT HOLE, a head shop I helped start and run in 1970, was an act of imagination whose origins are hazy to me now. As I remember, there were four of us—Alita, Maggie, John, and me—but Alita dropped out shortly after introducing me to the other two. Together, we sold counterculture paraphernalia in Coffeyville, a conservative town of 13,000 in southeast Kansas. I was working nights and weekends at a funeral home while finishing high school. John, the only one with a real job, put up the money and sold his photographs in the shop. Maggie had a young child and was the most practical and determined one among us.

We were driven, I think, by a longing to be part of what was going on in the rest of the world. We caught glimpses in Lawrence, the little countercultural oasis around the University of Kansas, and on TV. Certainly, it was an eventful year. I was anxious about the draft. I was worried my girlfriend might be pregnant. The state’s attorney general made national headlines busting KU students for smoking pot. That spring, National Guardsmen killed four students in Kent, Ohio. The day following, the Baptist preacher’s daughter and I wore black armbands to school and my American History class, taught by the basketball coach, awkwardly discussed the “current event” of the week. Afterward, Mr. Thomas conducted a straw poll. In my class of thirty, I was the only one who thought the shootings wrong and one of two who opposed shooting more students to stop the anti-war demonstrations.

Looking back over the trajectory of my life, I believe there was another motive at play in starting the shop. We liked creating a business. A seasoned merchant who we approached about a rental sniffed that out. While most people in town didn’t much like what they called the “hippie element,” he didn’t seem to care. He owned an older building a couple blocks from downtown that was perfect. He threw in some elegant glass jewelry cases he had lying around his warehouse and a silver embossed cash register with a mahogany handle on the side to open the till.

Maggie and I worked side-by-side at a leather table. I banged out simple belts, and she crafted fringed suede purses and vests. We hung them on a tree snag placed in the middle of a floor painted with stones—our idea of the shire. We bought papers and rollers and posters and a few items of clothing from some hippie wholesalers in Wichita. I once came home with a pair of tight-fitting stars-and-stripe bellbottoms that I wore to high school the next day and never lived down. On one trip to Wichita, they took us to a bar where I was shocked to hear Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young’s song “Ohio” playing on the radio. “What if you knew her, found her dead on the ground.” On the loud speaker, uncensored!

Steve, my first Jewish friend from New York, helped watch the shop. A student at the local junior college, Steve was willing to do and say things that were outrageous and funny to a Kansas kid, and I loved it. Others would show up to play guitars or just to hang out and feel cool for once. There were occasional trysts in the back. The disposable income of Kansas hippies being what it was, the business never thrived. Still, we had ourselves some fun.

The town fathers were none too happy, though. My girlfriend’s brother had recently returned from a tour in Vietnam, where he’d worked as an undertaker at the Ton Son Nuht airbase. He attended VFW meetings and shared with his sister that they were cooking up a plan to shut us down. The plan turned out to be throwing a brick through our plate glass window late at night. We didn’t have the money to repair the window, so we taped up a peace flag—an American flag with a peace symbol in place of the stars—to cover the hole. That prompted an editorial in the Coffeyville Journal about our dishonoring of the flag.

But broken windows and bad press didn’t do in the Hobbit Hole. Improbably drawn together, our little group couldn’t sustain our meager profits or life changes. I went off the college. I lost track of the others, though I’ve learned on Facebook that Maggie became an anthropologist, traveled widely, and has great-grandchildren. (Plus she’s a birdwatcher!) The Hobbit Hole fizzled more than ended. But it was a moment of sweet freedom. Upon our opening, Maggie was asked by the Journal: What if it doesn’t work out? “It will still have been worth trying,” she said.

FOR THE LOVE OF TYPE

An alphabetic genius

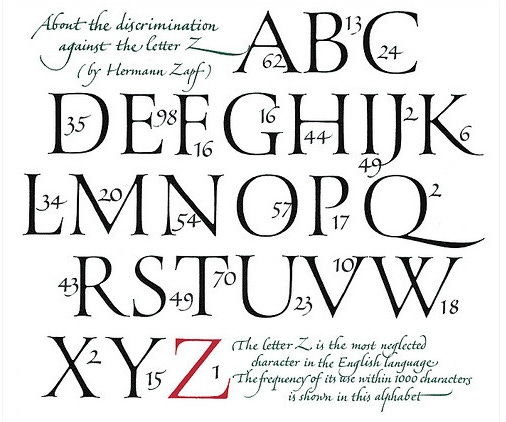

I BOUGHT a little blue book in the mid-1970s entitled About Alphabets. One of my first books on type design, it always occupied a prominent space on my studio shelf. The author, Hermann Zapf, is little known outside the cloistered world of type designers, but within it, he was a giant. He created an estimated two hundred typefaces, including Palatino and Optima He designed an alphabet for the Cherokee language. He designed dingbats. He adapted lead-type designs to photo-type and photo-type to digital type. All impressive, yet I most admire Zapf’s old-fashioned commitment to calligraphic and Roman letterforms—and his skill in producing them—as shown in his whimsical defense of the letter Z.

READINGS

Snippets of the week

Why Rothko turned to abstraction. “Though Rothko had always been trying to use his work as a means of expressing his emotional state in the rawest form possible, over the course of his life, it seems that he slowly lost faith in the artistic beauty which had once so captivated him. Yes, he still felt an inescapable pull towards the practice of painting. But, it was a conflicted pull, too, because, increasingly, he felt something close to that old biblical phrase repeating in his heart too; “vanity, vanity, all is vanity. . . Surely, there was a way of capturing something beyond form.. . something intangible—yet, somehow, more real.” —George Bothamley

For the love of octopuses. Kevin Dann profiles Jean Baptiste Vérany, who abandoned his father’s pharmacy business to paint cephalopods in the mid-19th century. And Maria Popova tells the remarkable story of a French seamstress, Jeanne Villepreux-Power, who became that century’s leading authority on argonauts. To study them in their own domain, she “designed and constructed one of the world’s first offshore research stations — a system of immense cages she anchored off the coast of Sicily, complete with observation windows through which she could study the argonauts undisturbed. Every day, she prepared food for them, rowed her boat to the cages in her long skirts, and knelt at the platform.” And then she invented the aquarium.

The invisible loving hand. “How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortunes of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it.” —Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, quoted by Robert Graboyes

Note to readers: A gallery recently returned a limited number of prints from my Outside In exhibit last summer and I’ve put them on sale at substantial discounts. For most, only a single print is available. To see the pictures, click here.

Oh, that story of your head shop in Kansas brought so many memories. I grew up in Indiana, which had (still has) a similar attitude toward the "hippiesque". The bellbottoms, the fringed jackets, the glass pipes - we tried so hard to be cool. We would have been so envious of your shop. The way you handled the attack - with poetry and posters - made me remember how that righteousness felt. I miss the optimism and the conviction.