Was that Photoshopped?

The reality of photography today. Some real Christian heroes. And a timeless ode to joy.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Mama, don’t take my Kodachrome

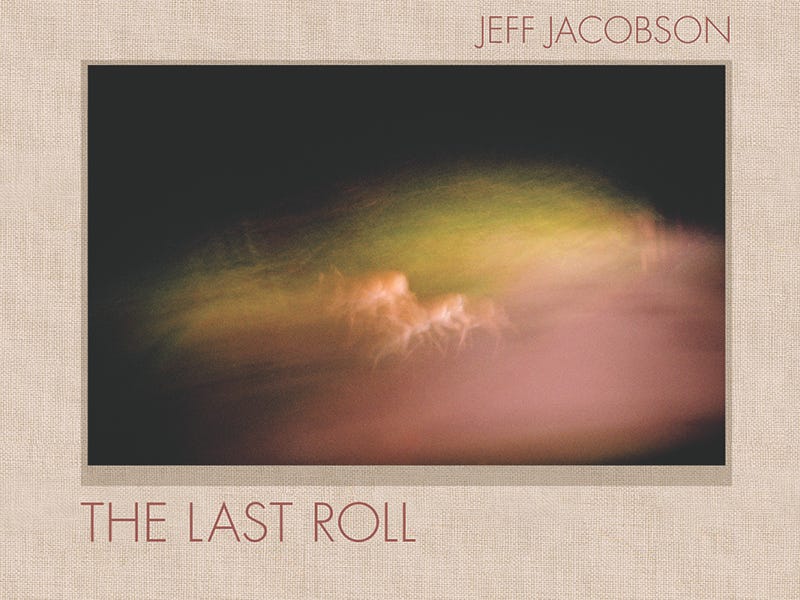

WHEN JEFF JACOBSON, a great photographer and friend, titled his final book The Last Roll, he was struggling with cancer. He remained optimistic about his recovery, but was acknowledging the end to come. And facing death, he created an inspired body of work.

The title also meant something else. Jeff shot in Kodachrome, a film beloved by many photographers and filmmakers. As a magazine art director, I loved it, too. Though more difficult and expensive to process, I preferred its warm tones and saturated color to the brighter and cooler blue/greens of Ektachrome, the other major color film from Kodak. And Jeff pushed Kodachrome to the limit. He was unafraid of bright flash or high sun, which in less capable hands and on a less versatile film would burn the highlights to white and produce shadows that were either too dark or too faded. He artfully deployed the film’s saturated color to create complex pictorial designs that encourage variable interpretations of the images.

In June, 2009, after a decade in which digital photography had largely displaced film, Kodak discontinued Kodachrome. The last roll was processed a year and a half later by Dwayne’s Photo in Parsons, Kansas, just a few miles from my former high school. “The twin realizations that my time on the planet and my supply of film were both finite have had a strangely liberating effect on me,” Jeff wrote. “My photographs are images of a world hurtling toward an uncertain future, made in a medium that has already ended, by a photographer confronting his own demise.”

TODAY, SEVERAL OUTFITS offer digital filters that reproduce the look of Kodachrome. I have a couple dozen such filters embedded in Lightroom, the version of Adobe Photoshop that I use to begin the the process of preparing digital photographs for printing or posting. Does that mean I’m using Kodachrome? Not exactly, but to an extent, yes. First produced by engineers in 1934, Kodachrome has always been a “look”—a way of interpreting reality that depended on the engineering of lenses and cameras as well.

When my photographs are exhibited, I’m frequently asked: Did you Photoshop them? I’m somewhat at a loss as to how to answer. The main tools I use in Photoshop—exposure, highlights and shadows, saturation, filters—are sophisticated versions of those available on an iPhone. I could say, “That’s like asking a photographer fifty years ago if they used a darkroom.”

But that would be unkind and, besides, it’s not what they mean. They want to know if the photograph is “real” or has been manipulated to show something that wasn’t there. In the past few years, that question has taken on special relevance as Photoshop and other software has added Generative AI—the capacity to generate images or parts of images by machines trained on billions of pictures.

The stakes are high. The gang symbols digitally added to Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s knuckles, and the subsequent denial of it, are reminiscent of past authoritarian leaders who airbrushed disgraced figures from official photographs. What happens if we can no longer believe our eyes?

I find it helpful to remember that photographs have always conveyed partial truths. Photographers shoot from a social perspective, particularly photojournalists. Yet that’s hardly a justification for abandoning photography’s documentary role any more than it is to give up on nonfiction writing.

On the recent fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, the New York Times published a tribute to the photojournalists who covered it. A hundred died doing so. These photographers were so effective in conveying the horrors of war, especially when published in widely read magazines such as Life and Look, that they shaped American public opinion and thus the ultimate course of the war. Recognizing that, the military severely restricted photographers’ access to later battlefields in Iraq and elsewhere. Was the Vietnam War’s death and dying real? In the overly politicized, hyperactive media cacophony we now inhabit, the veracity of those photographs would no doubt be challenged, even at the highest levels.

We have perhaps always asked both too much of photographs by insisting that they precisely represent reality and too little by failing to appreciate the social, aesthetic, and technical contexts in which photographic truth-tellers operate. Well into the twentieth century most photographs were in black and white, but the world never was.

Jeff began his career as a civil rights lawyer and social commentary was frequently embedded in his work. Yet he was keenly aware of the eye behind the camera and saw himself as an artist, not simply a documentarian. In many of his photographs, a partial view of a person or group of people both illuminates and obscures a bigger picture. Some suggest social critique or pathos, but usually with the warmth and gentle sardonic humor that characterized Jeff himself. Liberated by his heightened awareness of finitude, many photographs in The Last Roll veer near total abstraction, stirring alert viewers to consider a multiplicity of photographic interpretations of the real.

I honestly don’t know what Jeff would have thought of today’s Kodachrome filters and the digital turn they represent, but I suspect he would have regarded them as another brush in the artist’s toolbox. I would love to have asked him. –Kerry Tremain

For further reading on photographic AI technology, its social implications, and new documentary strategies, I recommend my friend Fred Ritchin’s new book, The Synthetic Eye. He writes, “Might we decide that we have had enough of ‘consumer entitlement’ and, instead, prioritize being informed citizens intent on upholding democracy? Rather than ‘Dream it. Type it. See it,’ Adobe’s slogan acknowledging the addition of AI-driven generative fill to Photoshop, might we insist on valuing the world in which we actually live?”

WORLD WAR II

Unorthodox bravery

I’M RARELY IMPRESSED by the behavior of Christians, let alone inspired. I do know that religion can motivate extraordinary moral courage and action. Martin Luther King Jr.’s faith was central to his achievements. Closer to home, my Christian friends Bonnie and Jerri, who I worked with in a community clinic, have dedicated their lives to helping others. And I recently discovered another inspiring pair: Bishops Stefan and Kiril of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.

Prior to World War II, Bulgaria’s established church, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, was quite similar to most other Eastern Orthodox religions. The church did, however, have a history of resisting political authorities, especially the Ottomans who ruled Bulgaria for nearly 500 years. They developed a healthy suspicion of those in power (kind of like Jesus, you might say). And crucially for this story, unlike most other Christian churches, it had no strong tradition of theological antisemitism.

From 1939 to 1941, German occupying forces moved steadily nearer to Bulgaria. The Bulgarians weren’t Nazis, but neither were they ready to fight the Germans. And in March of 1941, the Bulgarian head of state, Tsar Boris III, reluctantly joined the Axis. The Germans had sweetened the deal by “giving” them nearby occupied territories, including Thrace and Macedonia, which had been part of Bulgaria prior to World War I.

By the end of 1941, the Nazis had coerced the Bulgarian government into adopting the so-called “Law for the Protection of the Nation.” The law forced some Jews into labor camps, expropriated their businesses, and relocated them internally. Many Bulgarians opposed this legislation, but obeyed, however grudgingly. As the German ambassador in Sofia complained to his superiors, “The Bulgarians do not understand the concept of antisemitism.”

In early 1943, Germany made plans to deport fifty thousand Bulgarian Jews. These were mainly Sephardim living in urban areas who were integrated into the life of the country. Fortunately, the Bulgarians seemed to know exactly what “deportation” meant. Unlike other parts of Europe, including France, this Gentile population didn’t accept Nazi reassurances that their Jewish neighbors were simply being shipped “elsewhere.”

Bishop Stefan of Sofia, who led the largest congregation in Bulgaria, immediately penned a public letter to the Bulgarian government and Tsar Boris III. He wrote: “We cannot allow persecution of innocent people based on racial difference. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church, faithful to Christ’s teachings, cannot remain silent while injustice is committed against citizens of our country.” He also warned that the deportation of Jews would be “a crime that would stain the soul of the Bulgarian nation forever.”

Nonetheless, in March 1943, authorities in Bulgaria’s second largest city, Plovdiv, began rounding up Jews and detaining them in makeshift holding pens in the train station to await transport to Treblinka. Their local Bishop, named Kiril, rushed to the station along with three hundred of his followers. He confronted the officers and reportedly declared, “I will not allow this. I will lie across the tracks and you will have to pass over me before you take these people.”

He then sent an urgent telegram directly to Tsar Boris III, which said, “Your Majesty, in the name of Christ, I beg you to stop the persecution of the Jews. There is no Christian morality in such acts.”

Fortunately, many ordinary Bulgarians also opposed the deportations and a number of politicians acted against them. Dimitar Peshev, Deputy Speaker of the Bulgarian Parliament, led a revolt and organized a petition signed by forty-three of his fellow legislators to halt the deportations.

But the church was key. Through their actions, the bishops enabled Bulgaria to successfully resist enormous German pressure. The deportations were cancelled, saving tens of thousands of lives. The Bulgarian church leaders took a stance based on their religious faith, but also one that was national and moral, reminiscent of Martin Luther King, Jr. in our country. Sadly, their example stands in sharp contrast to the actions of many Christian leaders today. –Barbara Ramsey

VIDEO OF THE WEEK AND BEYOND

Undying joy

I FIRST HEARD Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as a young boy. For years, it hummed in my head and through my lips like a Beatles song. I memorized the words of the Ode to Joy chorus—Alle Menschen werden Brüder Wo dein sanfter Flügel weilt—which envisions a brotherhood of all men under the gentle wing of Joy. That a work of art from a composer such as Beethoven or an artist such as Goya can speak to us so poignantly across centuries remains for me a great mystery and gift. It affirms our humanity against the cruelties we know all too well. Years ago, I came across this video of a 2012 flash mob in Som Sabadell, Spain, performing the Ninth, and have watched it many times, never without welling up. –KT

RECENT PHOTOGRAPHS

Snippets: Democrats

THE RELATIONSHIP between trade policy and democracy is no niche concern. For decades, American workers, even those with tough and nimble union leaders, have been denied a vote over their economic future. They have watched corporations shutter plants overnight, seen their contracts scrapped and pensions downsized, experienced the humiliation of being forced to train foreign replacements, and been left helpless as whole communities were robbed of their civic identity. This history is a reminder that American workers have a legitimate stake in demanding and defining fair trade. –Justin Vassallo in Compact, “The Perils of Democrats’ Trade Strategy.”

THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY must choose between two basic strategies. The first is to hunker down, change nothing, and wait for some catastrophe—deep recession, failed war, or a breach of the Constitution—to deliver victory. This strategy has the disadvantage of placing the party entirely at the mercy of events. It puts the party in the position of tacitly hoping for bad news—a stance the electorate can smell and doesn't like. And it is a formula for purposeless, ineffective governance. The other strategy, active rather than passive, is to address the party's weaknesses directly. Thus the next nominee must be fully credible as commander-in-chief of our armed forces and as the prime steward of our foreign policy; he must squarely reflect the moral sentiments of average Americans; and he must offer a progressive economic message, based on the values of upward mobility and individual effort. –Elaine Kamarck and William Galston, The Politics of Evasion, 1989. Quoted in Persuasion.

THE PERCENTAGE of Americans who view President Trump favorably is 43, while those who rate him unfavorably is 54 percent. The percentage who view the Democratic Party favorably is 36, while those who rate the party unfavorably is 55 percent. –The Economist/YouGov Poll, April 25-28, 2025

When people ask me if my images have been “Photoshopped”, I proudly answer yes, absolutely. For those of you that were part of the photo/graphics/publishing industry in the 80’s and early 90’s, the question was, “was it Scitexed”. Photographs have been manipulated long before digital technologies were available. Ever see what Ansel Adams image “Moonrize, Hernandez, New Mexico” really looks like? Go ahead, Google it!

From the time that humans have walked this earth, we have continued to imagine, invent, build, explore, and create, it’s in our nature. Often, each new creation was questioned and criticized by many who were uncomfortable with the changes that were ahead. It’s interesting that many of these inventions and creations have been meant to make our lives more comfortable but seem to generate the opposite response in us.

Kodachrome was also my favorite film back in the day. I have boxes of Kodachrome slides that I would proudly project on any wall to family and friends. But in the early 90’s I felt change was in the air and became an early adapter of the new digital technologies that were beginning to present themselves. I personally know many colleagues who missed getting on the digital train that was rolling down the tracks. Some lost their businesses and livelihoods, some even their homes. By the time Kodachrome was discontinued, I had already been making photographs digitally for 17 years.

Today is no different. AI is here to stay. The genie will not go back into the bottle. I can honestly say, AI scares the hell out of me! Not so much as to what AI can do, but mostly what humans will do with it. As with all our advancements and inventions we me must learn how to control them and use them to our benefit, not our detriment.

I met Sarah Adams, Ansel’s granddaughter at a trade show that I was demonstrating a new digital camera at. I said to her, “Ansel must be rolling over in his grave with these changes in the world of photography”. Her response to me was that she believed her grandfather would have loved it and eagerly adopted it. We’ll never know for sure, just like not knowing if Jeff would’ve used the Kodachrome filters, but they’re her to stay, so we better get used to it!

I could say, “That’s like asking a photographer fifty years ago if they used a darkroom.” This is an important thought.

The creation of art has always existed on the edge of new ideas. As I talk with people in the tech industry, I find the discussion about “what influences what”, a compelling investigation. Visual reality is seen from the farthest reaches of the universe to the mystery and exploration of the Higgs boson features of the atom. Our dream-like intuitive perception with thoughtful explorations might be one of the most accurate sensors of visual reality. Visual interpretations continually take on new forms demanding a new language. It does not exist unless you can name it. At one time, only black and red existed.