The sublime and the putrid

War and peace in Yosemite, how to stink up a corn patch, and life on a sub-zero sub.

BIRDS

A BEWICK’S WREN family moved into our yard three years ago and I’m always happy to see them and hear their bold, distinctive song. Bird names referencing historical figures are now set to change, in large part because many of the birds’ namesakes, such as John James Audubon, held noxious views on slavery or other contemporary issues. The Bewick’s Wren appears to have a more commendable provenance. The British wood engraver and illustrator Thomas Bewick spoke against cruelty to animals, war, and poverty. He invented a method of wood engraving that enabled higher quality, less expensive illustrated books and crafted several, including popular editions of Aesop’s Fables. Bewick is best known for A History of British Birds, which, with its beautiful engravings and detailed descriptions, was a forerunner of field guides. Both volumes of the book were instant bestsellers when published in 1797 and 1804, and turn up multiple times in Charlotte Bronte’s novel, Jane Eyre.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Yosemite’s redemption story

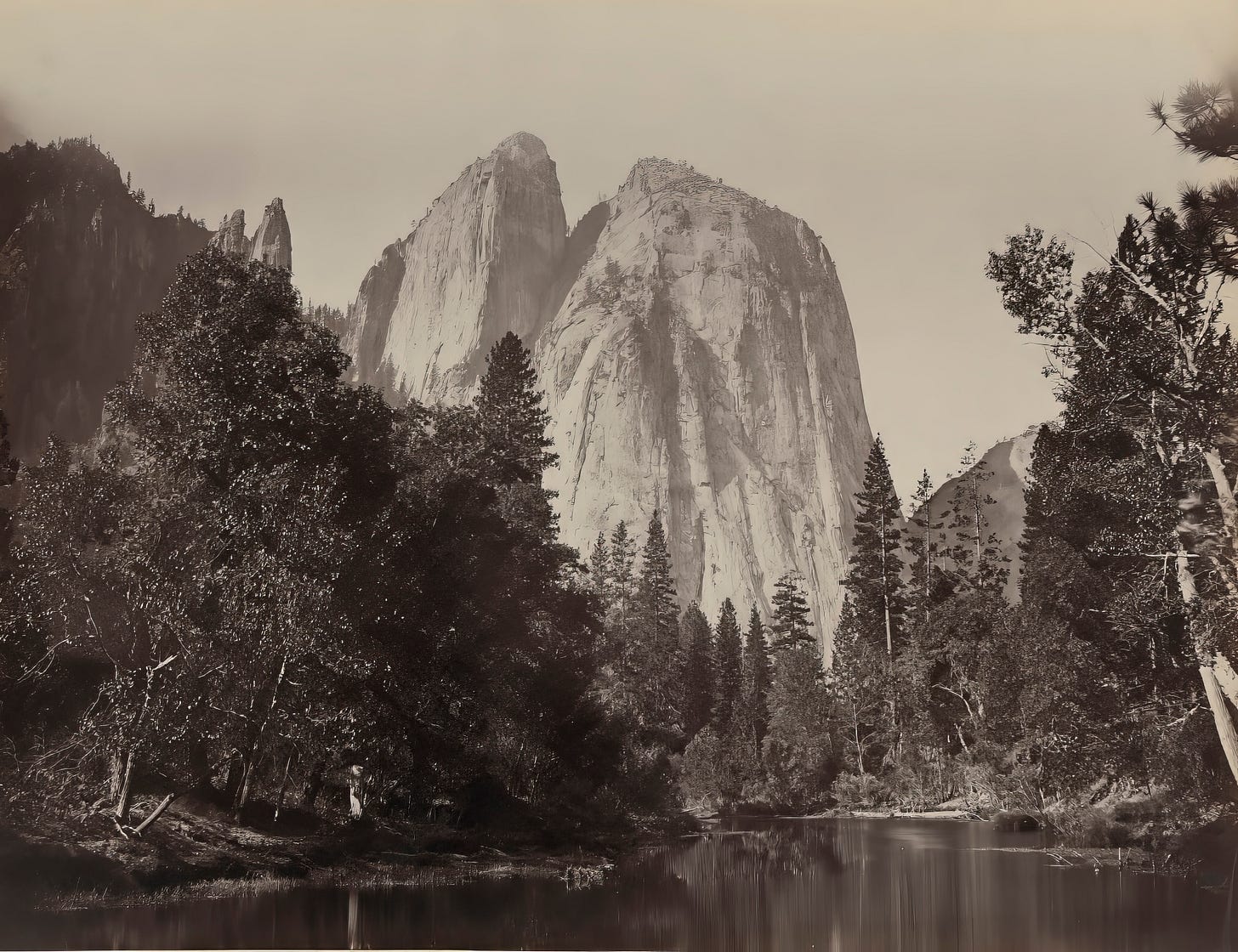

WHEN CARLETON WATKINS exhibited his photographs of Yosemite in New York City in 1862, he could hardly have guessed at the show’s artistic and political repercussions. “As specimens of photographic art they are unequaled,” wrote a New York Times critic of the exhibit. “Nothing in the way of landscapes can be more impressive.” With his mammoth camera and 18 x 22-inch glass-plate negatives, Watkins had virtually invented Western landscape photography. But Watkins’ exhibit at New York’s Goupil Gallery did more than lay down a new marker for landscape photography. For many Americans, east and west, his photographs helped transform Yosemite into a place of legend.

Watkins’ New York debut directly followed the Mathew Brady Gallery exhibit of Alexander Gardner’s photographs of the dead at the Battle of Antietam. The gruesome images fascinated and horrified New Yorkers, who lined up to see them. Watkins photographs naturally had a more salutary effect. Following the exhibit, Yosemite was championed by leading voices as a healing symbol for America. Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune and Thomas Starr King of Boston Evening Transcript extolled the ennobling virtues of Yosemite’s grandeur in contrast to the sectional political strife that drove the nation to civil war. In the last year of the war, Frederick Law Olmsted wrote that “contemplation of natural scenery” promotes the “health and vigor” of the mind and body, echoing the idea of Yosemite as a place for America’s wounded psyche to heal.

Perhaps. But this view overlooked the state’s forcible removal of the Ahwahneechee in 1851. Late in life, Chief Tenaya’s granddaughter recalled seeing her people sifting through piles of ashes to find edible acorns after the Mariposa Battalion burned their winter food cache. Most had already been removed to a reservation in the Central Valley by the time Watkins began his Yosemite project in 1861.

When a Civil War-weary Congress considered legislation to protect Yosemite, Watkins’ pictures lent support to the law’s passage. California Senator John Conness reportedly passed them around before introducing the Yosemite Grant—the first act of the federal government to protect a scenic landscape—in the spring of 1864. Congress was just emerging from the bruising battle over the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery. It was the right moment. The act sailed through both houses with little discussion and was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30, 1864. For many, Yosemite’s beauty seemed to confer the sense of divine grace that Lincoln appealed to in his Second Inaugural: “With malice toward none, with charity for all… let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds.”

—Adapted from “Yosemite: A Storied Landscape,” which I created for California Historical Society and is free to download on Apple Books.

TALES FROM ALABAMA

W.T. repels the raccoons

By Barbara Ramsey

MY MOTHER ALREADY HAD many friends in Alabama when she moved back there in the mid-1970’s. Then she made new ones. She quickly got to know her neighbors, well aware that life in the country depends on knowing folks. With frequent hurricanes off the Gulf of Mexico, it’s vital to be on good terms with the local roofer. Calling on a neighbor with a tractor is helpful if you’re looking to expand your tomato patch. Being friendly with the daughter-in-law of a certain judge can come in handy in all manner of situations.

One of her new friends was W.T. Purvis, a local landowner whose family was long established in the county. W.T. was known to be little crotchety and always up to some scheme or another. He could afford single-malt scotch, but preferred homemade liquor. He had friends who went shooting in Texas at exotic animal ranches, but he preferred Alabama game. He was surrounded by good ole boys with the latest thing in trucks, rifles, and gun racks, but he liked pickups with a lot of mileage and weapons that were time-tested.

One day when I was visiting from California, W.T. stopped by to see my mother, accompanied by his friend, Doc Dearmon. Doc was not an actual doctor. He was given his nickname for feats no longer remembered by anyone, including Doc himself. I was in my early thirties. W.T. and Doc were both near seventy.

After some coffee and sharing of local gossip, W.T. and Doc said they’d best be off. They had an errand out in the woods, something having to do with the upcoming deer hunting season. Mother spoke right up and asked if they would please take her ignorant daughter along for a lesson in local hunting practices. I wasn’t sure what she meant but was generally up for an Alabama adventure.

We crammed into the cab of W.T.’s pickup along with all manner of equipment, food wrappers, and general debris. In the back were half-dozen oil drums with lids. They looked pretty heavy, which was good because the truck needed some ballast on the dirt roads W.T. favored. As we bumped and rocked our way across the county, W.T. and Doc pointed out local sights and said what happened where, though I couldn’t always tell if what happened was last week or back in 1947.

Finally, we stopped in a corn field surrounded by brush and a six-foot-high wire fence draped with feed sacks. The fence, I learned, protected their corn from deer right up until the first day of deer hunting season, when they’d take down the wire fencing and wait in a nearby blind. This was illegal, but no one in the county seemed to care.

Unfortunately, this defense was no use against the raccoons who filled the nearby woods and laughed at fences. Raccoons could strip a cornfield like this in an evening and still be home for the ten o’clock news. But W.T. and Doc knew how to repel raccoons, and that turned out to be the purpose of our excursion.

They took down all the feed sacks on the fence and brought them back to the pickup. Then they opened up the oil drums and suddenly a rancid stench filled the air, burning my nose and eyes. “What the world is that?” I asked. Turns out they’d been saving up their own pee all summer. Like me, raccoons are repelled by the smell of fermented human urine. The two friends dunked the feed sacks in this foul liquid and re-draped them over the fence, working methodically to make sure no length of wire was uncovered. “Everthin’s good for somethin’,” W.T. said.

FOR THE LOVE OF TYPE

Nuthatch Nouveau

NUTHATCH NOUVEAU is the latest in my Birds-of-a-Type card series. Christina Torre of the P22 Type Foundry designed this Art Nouveau font. The border was drawn by the late nineteenth-century Franco-Swiss decorative artist Eugène Grasset. I took this photo of a busy Red-breasted Nuthatch in Washington’s Fort Worden State Park.

Snippets

NUCLEAR FREEZE. A recent photo essay in the New York Times reported on a Navy submarine exercise in the Arctic. My friend Paul Aniotzbehere, who served on a nuclear sub and has told me of harrowing cat-and-mouse encounters with Russian and Chinese ships around the Pacific, had this response to the story:

My boat, The USS Permit SSN 594 patrolled the Arctic in 1969. We didn't surface, but stayed below, threading the needle through the ice. I remember how cold it was. I was hot-bunking with Moose Tulabee and welcomed his body heat, which lingered in our "fart sack," when I climbed in. We lined the berthing area deck with cases of beans and corn, hoping they would create a layer of insulation. Not much success with that idea. Since we home-ported in Hawaii, there wasn't a jacket on board, so we stuffed our thin, one-piece jump suits—we called them “poopy suits”— with paper towels. It was all worth it for the extra sixty-seven dollars a month we earned as submarine sailors!

ROMANIAN REBEL. “After you’ve experienced the clichés of Communist propaganda, you can easily spot the mental structures underlying the impulse to reduce the complexity of the world down to one huge power struggle in which everybody is either an oppressor or a victim. This is why having lived through Communism has become very useful in contemporary America, and it's why the few of us who denounced the insanity of Communism when it could have cost our lives won’t keep our mouths shut now that America is losing its mind.” —Alta Ifland

A masterful use of the subtext. medium. First rate. A inspiration. I f imitation is the highest compliment,, I am moved to create a site of. My own. Thanks!

Wow! Yosemite, rancid pee and another Bird Type card! A trifecta! (I really want a set of the cards when you finish! Which might be...never?)