On my approaching heart surgery

By Barbara Ramsey. Plus: A cinnamon treat, the evolution of skin color, and some Berkeley characters.

BIRDS

I’VE MIXED UP my local teals before. With dim light and a dollop of misplaced hope, I’ve mistaken Green-winged Teals for the Blue-winged variety, which is less common on the Olympic Peninsula. But there can be no confusing this bird or questioning why it’s named a Cinnamon Teal. I spotted him on the edge of a stream in the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge, a half-hour north of Portland and just off the Columbia River. Friends had long advised me to go, and I made it there on a return from southern Oregon last summer (ah, summer). The creek, lake, and wetland within is ideal territory for water birds. I saw groups of colorfully plumed Wood Ducks floating down vegetated streams shaded by mature trees. In the tall grass, I caught a lone Sandhill Crane hunting prey. Bald Eagles and Red-tailed Hawks cruised the sky with similar purpose. This Cinnamon Teal was aware of me and seemed torn between scampering off and continuing to forage. In this picture, I sense a wary eye.

WHAT IS BARBARA THINKING?

Heartfelt

I’LL BE HAVING heart surgery in another month. Which makes me think about something I witnessed long ago.

In medical school, I was once allowed to scrub in on an aortic aneurysm repair. The patient’s midsection was opened and the abdominal contents temporarily pushed aside. I was instructed to look from the abdomen upwards toward the diaphragm. There, near the center of the diaphragm, I could see the rhythmic quivering created by the beating heart above. The surgeon told me to slip my hand into the abdominal cavity, directly beneath the patient’s heart.

It was astounding. I’m not a religious person, but I believe in the miraculous. The movement of that person’s heart was miraculous to me. And what I found even more miraculous was the fact that I had the exact same kind of organ inside my own body. A living heart! This astonishing fist-sized muscle of flesh has been beating since before I was born. It’s never stopped, not once for more than seventy years—beating, for all intents and purposes, utterly of its own volition.

How can a heart possibly beat on its own, year in and year out, without our having to serve it, to worship it, to make constant sacrifices to it? My doctor-self may know how the heart manages to beat, but my regular person-self is mystified. Which is why I would have made a great rank-and-file Aztec: exposing the living heart makes sense to me as a sacred act.

As a doctor, of course, I understand the mechanics of a beating heart, and I’ve found myself surprisingly dispassionate about my upcoming surgery much of the time. Also, as my father was a surgeon, I’ve always thought of them as ordinary people, guys who come home late and grumpy and just want to watch Bonanza on TV. A person who enjoys a round of golf and a couple of martinis on his day off.

An Aztec priest would never watch Bonanza. He would become familiar with the thirteen heavens and the nine netherworlds, and be intimate with the shrewd, elusive god of fortune. Like my heart surgeon, an Aztec priest would be schooled for years in advance, then shrouded in a special gown and mask, and finally step into a place of great solemnity. A group of assistants would hand him special instruments to aid in the performance of a series of acts somehow both ritualized and spontaneous.

My surgeons, like those priests, will attend to their ceremonies. An anesthesiologist will render me unconscious, put a tube down my throat, then assume control of my breathing. Next a team of surgeons will crack my breastbone, open my chest cavity, and put me on a machine to circulate my blood. Then they will cut into the left side of my heart. Over the next three or four hours, they will remove an abnormal chunk of muscle that’s been partially blocking blood flow to my aorta, repair or replace my faulty mitral valve, and slice into parts of my left atrium. This last maneuver will be an attempt to stop my atrial fibrillation and reduce my chance of having a stroke. But it could also result in my heart failing to beat properly, so they may have to slip in a pacemaker before they sew me up again.

Unlike those long ago priests, my surgeons intend to keep my heart in my chest and encourage it to beat in the right way. They will seal it back up again once they’ve finished their healing ceremonies. If they succeed, the surgery will likely extend my lifespan and improve the quality of my life. And I will remain in whatever netherworld I currently occupy. —Barbara Ramsey

EXHIBITS

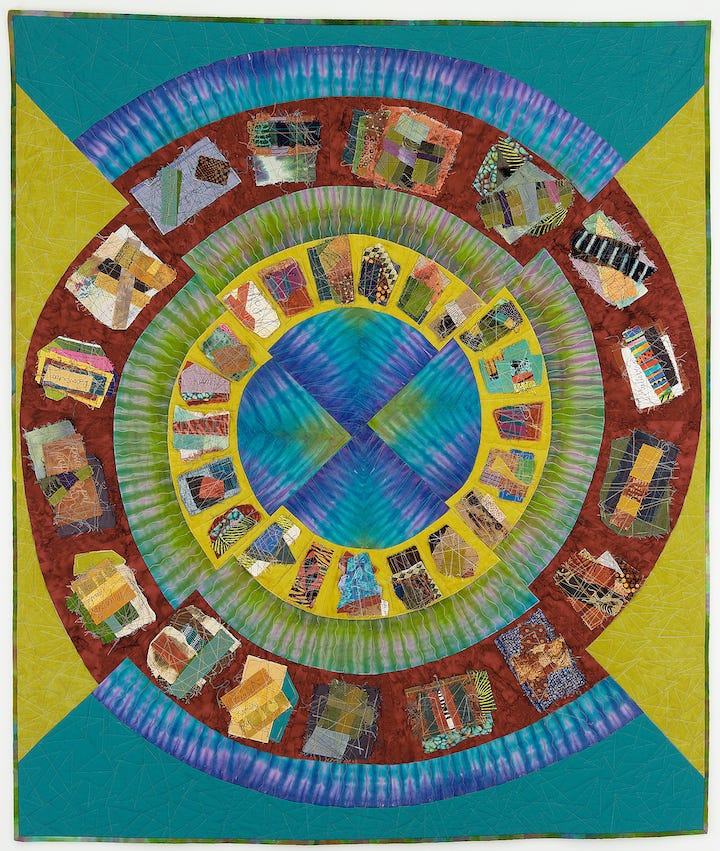

BURST OF COLOR, the fiber arts exhibit at the Northwind Art gallery has been extended through the end of February. It features two of Barbara’s quilts, including the one above, Ratcheted Mandala for Hildegard. Jeanette Best Gallery, 701 Water Street, Port Townsend WA.

THE 17TH ANNUAL CVG Juried Show of Washington State artists continues through February 23rd. My picture, Red-tailed Tropicbird, won the second place award in photography and digital art. Collective Visions Gallery, 331 Pacific Avenue, Bremerton WA.

LINDA OKAZAKI’S retrospective, Into the Light, runs through February 25th. Linda will have a book signing for the catalog on February 4th at 3pm. Bainbridge Island Art Museum, 550 Winslow Way East, Bainbridge Island, WA.

EVOLUTION

Why do we have different skin colors?

I’VE CEASED BEING surprised by Barbara’s range of esoteric knowledge. On an evening stroll, we passed several people walking dogs that wore cloth coats. That prompted me to ask, “Why did we lose most of our fur?” In short, the answer is that in the warm climates of our origin, the ability to sweat gave us an advantage in traveling long distances. Several other animals can outrun us, but they have to stop and pant to cool off. Barbara learned this explanation in part from Nina Jablonski, a paleobiologist at Penn State. Jablonski has also studied the evolution of skin color. Why such variation?

Vitamin D is the key. We need it and our ability to produce it in our bodies is dependent on UV radiation from the sun. But as we know, too much can result in skin cancer. Melanin, which causes the skin to darken under UV light, protects us, and UV rays are most intense in the equatorial regions, including Africa, where Homo sapiens got its start. As populations migrated away from the equator, they evolved lighter skin to enable more Vitamin D production with less UV radiation. Thus the historic distribution of skin color correlates with the distribution of UV radiation on earth. Voila!

“What about Chuna?” I asked Barbara. Chuna is a Yup’ik friend whose people live in Alaska, far from the equator, but whose skin is light brown. She had anticipated my question. The Yup’ik and other northern groups eat a lot of fatty fish, which contains high levels of Vitamin D. So they require less UV radiation. Jablonski says that in the current age, when people with variations in skin color move around the globe, we need to pay attention to the implications of too much or too little UV light. Here in Washington, the hours of sunlight shrink dramatically during the winter. Now, when I swallow the daily Vitamin D supplement my doctor prescribed, I know why.

FOR THE LOVE OF TYPE

Chez Goines

DAVID LANCE GOINES, who died a year ago, had his print shop on the first floor of a rose-colored building on Martin Luther King Way, three blocks from our former home in Berkeley. He was principally known for the posters he created for numerous East Bay events and organizations. Goines defined a certain North Berkeley aesthetic, along with his former paramour, Alice Waters, whose cookbooks he illustrated, posters he designed, and weekly menus he printed for her restaurant, Chez Panisse. They both helped revive the Arts & Crafts tradition that had thrived in the neighborhood in the early 1900s. A famous type designer from that era, Frederick Goudy, who created the Berkeley typeface now used by the university, had also lived for a time in North Berkeley. But his studio and drawings were destroyed by a devastating fire in 1923 that burned much of the neighborhood. Goines’ shop, Saint Hieronymous Press, was a few blocks from the Hillside Club, one of the remaining physical vestiges of the earlier Arts & Crafts period.

By coincidence, I just met someone here in Port Townsend whose sister is a bartender at the Chez Panisse and has lived in the Goines building for forty years. Goines was picky about who could rent there—several tenants were associated with the restaurant—and vacancies were rare. Luckily, when I was looking for an apartment for my nephew and his girlfriend, I had a referral from a friend of Goines. Dressed in black and sporting his signature handlebar mustache, he met us in the apartment and, after checking us out, agreed to the rental. But when I pulled out a checkbook to pay the deposit, he reeled back with a look of horror. “Oh, no, I do not deal with the filthy lucre!” he said and referred me to his accountant. This was the unrelenting anarchist and Free Speech Movement veteran who once wrote and printed a book about how to start a bar fight. And yet, what elegance and discipline he demonstrated in drawing these letterforms.

Thank you for reading. We welcome your comments! COMING NEXT ISSUE: A doctor learns a lesson.

I don't know much about the Aztecs, Barbara, but I'm a veteran of two heart surgeries. Unfortunately, the first which was a mitral valve repair was supposed to last 15 years, but only lasted 5. The doctor was older and quite personable and I felt confident that he would do a good job and, even though I had no symptoms of any kind, I trusted my cardiologist and went ahead with it. I'm a fatalist and a willing victim perhaps more like an Aztec mounting the pyramid than I would have thought.

The second surgeon was strictly business with no bedside manner, but he replaced the loose teflon ring and floating sutures with a pig valve, which is certainly ironic and probably miraculous. But the results speak for themselves... I felt better in a couple of months unlike after the first surgery when I was still struggling two years later.

I wish you all good luck with your operation and that your heart is returned to you better than it was.

Barbara, thank you for such an eloquent description of surgery, in particular your heart surgery. I tend to be a practical person when it comes to such mechanical systems, but your poetical description has me rethinking the beauty that exists in our natural functions. I wish you good health and many more years to pursue your endeavors. The Fiber Arts show is delightful. Thanks for your beautiful contributions.

As always Kerry, another wonderful photo! The "side-eyed cinnamon teal" sounds like a good band name to my spouse (former musician)!