Lonely hearts and pretty lies

THE TOWN, Part Two, in which I discover sex and confront death. Plus: the annoyingly poor logic of Sherlock Holmes, and an Optima Owl card.

PERSONAL HISTORY

THE TOWN describes experiences I had while in high school that changed everything for me. The essay is divided into three parts. In the first installment, in the July 1st edition of Wild Things, we meet the town’s Black doctor, Raymond Wilcox, his wife Brianna, and their blind son Butch. The final installment will appear in the next edition. Though I have altered the names and a few details, these are true stories.

II. Karla

IN THE SUMMER OF 1968 I got my first paid job and had sex for the first time, with Karla, in a VW Bug parked in a wheat field. Her family owned one of the two white funeral homes in town and her grandfather hired me to wash the cars, mow the field surrounding the building, and do odd jobs. It was my first experience of dead people, though I was rarely around the bodies. Mostly, I rode the mower for mindless hours in the heat, inhaling a brew of gasoline and cut grass and looking out for killdeer nests. Some nights, Karla and I snuck into the chapel to make love.

When the summer ended, I landed a part-time job in Mann’s Funeral Home, the other white one. Karla’s family wasn’t altogether happy about it. Mr. Mann never said a word. Karla’s father, who was Mann’s age, had died in heart surgery when she was three. When he was old enough, Karla’s brother had taken over the business and built a modern funeral home on the edge of town. But Mr. Mann headed the county draft board. Her brother ended up sorting body parts at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in South Vietnam and laundering money to pay the mortgage on the new building.

Located downtown in an old white shingled mansion, Mann’s Funeral Home had a wide, curved lawn with Bermuda grass that he dyed green in the winter. I mowed, cleaned and shined the four cars, picked up the newly dead in the hearse, and helped the two embalmers wash the bodies.

On week nights, I watched the place. When we had a body in state, I wore a coat and tie and guided visitors to the coffin to pay their respects. Occasionally, there were long evening wakes, but many nights the funeral home was empty and quiet except for the clocks. If I had homework, I’d sit by the phone upstairs. I was never to let it ring more than twice. The line was connected to Mr. Mann’s house and he’d often pick up in case there was a call from the hospital.

When I closed up at ten, I had to lock the front of the building and exit out back through the embalming chamber. The room was large, with pumps, sinks, and ridged enamel tables. Often there were one or two bodies covered with sheets to the neck. The light switch was on the near side of the room and the exit door on the other side, so I’d have to turn off the light and cross the floor in the dark. I never got used to it.

One evening when there were no bodies in state. I went down to the basement where I could watch TV, which Mann frowned upon, and smoke cigarettes, which he forbade. I kept my ashes in a jar lid that I emptied into the brick incinerator across the parking lot. I was walking towards the incinerator when phone rang. I burned my finger snuffing out a Marlboro, ran in, and lifted the receiver on the third ring.

“I’m dead, come pick me up.” I recognized Butch Wilcox. I heard the click when Mr. Mann picked up.

“Mann’s Funeral Home,” I said, keeping my voice level.

“I’m soooo dead, puhleeeze come pick me up.”

“May I ask who’s calling?” Another click. Mann hung up.

“You’ll get me fired, Butch.”

“I’m at the bowling alley,” he said. “Pick me up after work.”

At night, teenagers “dragged the gut,” driving up and down Eighth Street waving and honking. At the west end, we parked at Gary’s dad’s A&W. Sometimes, I’d go with the small cohort of hippies up to Big Hill to smoke dope.

When Butch rode with me, some kids would snicker the next day. One of the football players liked to throw an elbow in my ribs when he caught me in the hallway between classes. Another asked how I liked chocolate dick.

On weekend nights, I’d pick up Karla to go make out next to the river. When I drove her home at night, I’d sit with her in the driveway. We’d hold each other for a few minutes and I’d feel her tensing up before she went in the house.

Her mother drank heavily. She smoked her cigarettes with one hand and propped up a drooping eyelid with the other. She was sleeping with her father-in-law, who locked up his own wife in their house and turned off the phones. He said she was bad in the head. On a trip to pick up a mower at his house, I once saw frightened eyes peering out from behind the dark screen door.

On the nights I took Karla home, I waited in the car for awhile. From the driveway, I could hear her mother scream at her, calling her a slut and a whore. Karla would shoot back out the door, climb in the car, and wail in my arms. Her mother would beg forgiveness in the morning.

The next year, when her mother died of a stroke, Karla said we couldn’t have sex anymore. I didn’t say anything for a minute and then softly asked why. “Mother’s up in heaven now and Dad will tell her what we’ve been doing,” she said, and wept. Her resolve left her within a month but her remorse never did.

Coming next in Part Three: Sandy, an ugly rumor about Dr. Wilcox spreads, with tragic consequences.

WHAT’S BUGGING BARBARA?

Infinite impossibility

By Barbara Ramsey

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” —Arthur Conan Doyle, Sign of the Four, 1890

I WAS THIRTEEN when I first read a Sherlock Holmes story. I was already obsessively familiar with the Nancy Drew mysteries and comfortable with the format—a detective with a ploddingly useful sidekick. But Conan Doyle felt like a real writer and Victorian England a richly exotic place. I got hooked on Sherlock.

Still, the “eliminate the impossible” line rattled around in my brain for years before I stopped to examine it. And then I was outraged. How could this piece of nonsense slip past Conan Doyle’s editors?

To discern who stole the diamonds, must you really waste time eliminating all the people who couldn't possibly have stolen the diamonds? Consider that London in Sherlock’s heyday had a population of four million people. That’s 3,999,999 people to eliminate as suspects before you nail your man. Alternatively, imagine you have three prime suspects, all with motive, means, and opportunity. None have an alibi. Multiple pieces of evidence point to one of the suspects, but there’s nothing that conclusively eliminates the other two. Do you assume they all did it because of your inability to eliminate any of the three?

Then there’s the constantly shifting nature of the impossible. During Conan Doyle’s lifetime, here’s the short list of things that went from the impossible to the possible: the lightbulb, internal combustion engine, airplane, radio, and antibiotics. The zipper, for god’s sake.

But who truly cares about an aphorism mouthed by an imaginary character invented more than a hundred years ago by a guy who believed he could communicate with the dead? Why waste a second’s indignation? Here’s why: 1) I live to be incensed, and 2) even now, authors quote this line as if Holmes were Wittgenstein.

From Isaac Asimov to Neil Gaiman, writers trying to give their investigators some street cred have them spout this Sherlock quote. The eponymous physician in the series House says it multiple times to show that he is a cool and calculating man of science. And as a huge fan of Vulcan logic, I was disappointed to learn that in 1991, in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, Leonard Nimoy as Mr. Spock quotes the line in utter deadpan. Again in 2009’s Star Trek, Zachery Quinto playing a younger Spock repeats it. This adds insult to injury.

Please think carefully about the idea for a minute. The impossible—what are its constraints? How about...almost nothing? Eliminating the impossible is, simply, impossible. In our universe, most of us are stuck with the possible. In the Star Trek Universe, the impossible—from Klingons to Romulans to Ferengi—can be franchised into infinity through the writers’ imagination. The possible is enormous enough, but eliminating the impossible? In the words of critic Anthony Lane, channeling an impossibly wise Yoda, “Break me a fucking give.”

BIRDS-OF-A-TYPE CARD SERIES

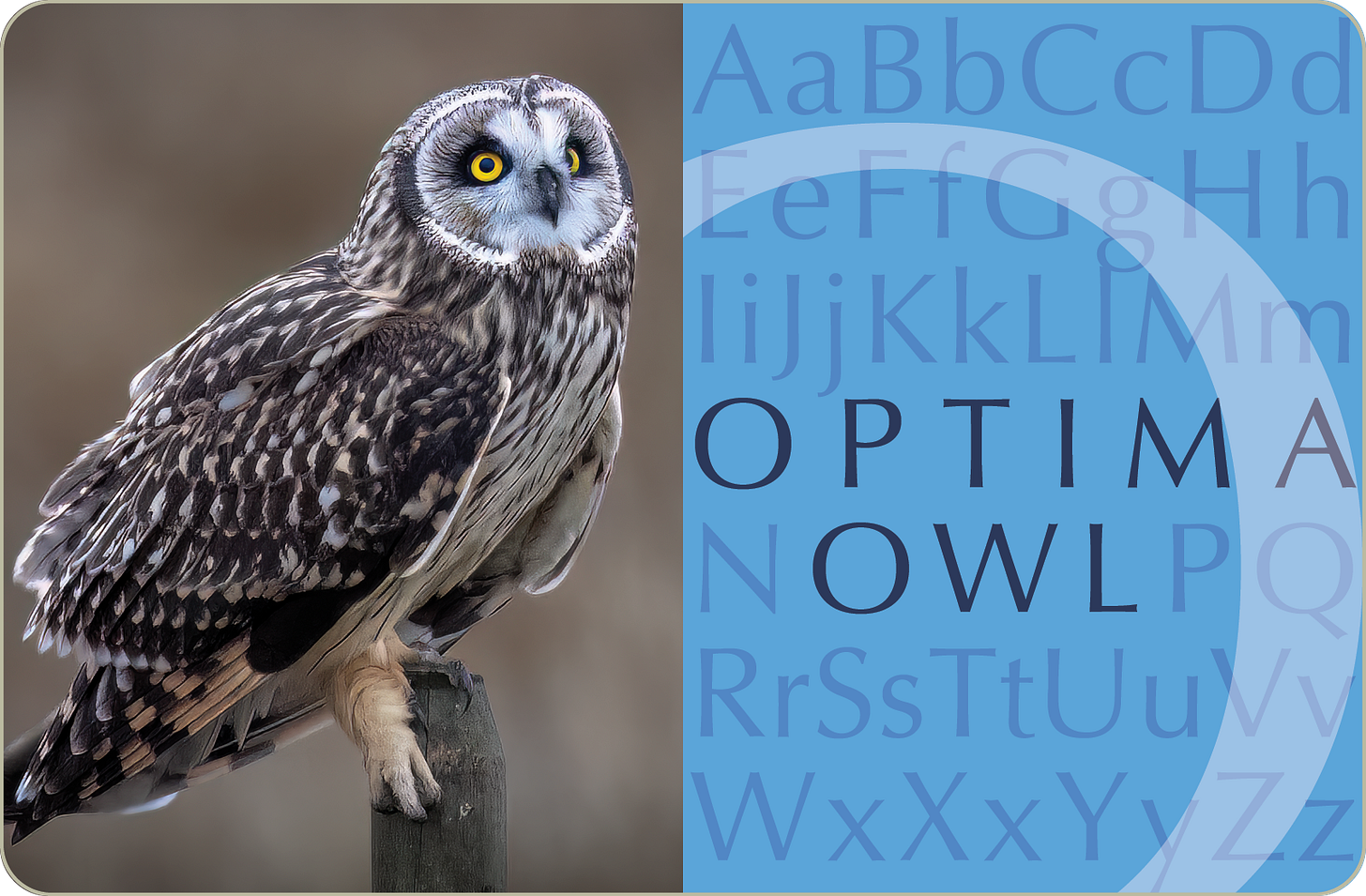

Optima owl

SHORT-EARED OWLS, one of the few owls that hunt during the day, have attracted a lot of attention from local photographers in recent years. In the winter months, they are not hard to find in Skagit Valley north of Seattle. On the day I photographed this owl, the bird had its own group of paparazzi. At least a dozen cars and vans were parked on the side of one of the narrow roads that crisscross the area. For these owls, the straw-covered river valley provides rich hunting grounds. Northern Harriers were scouring the same territory and Bald Eagles occupied a tree down the road. When the owl took off, I followed it across the road, where it alighted on a post. This picture was featured on a ten-foot-tall banner at the entrance to the Outside In exhibit last summer in Port Townsend.

HERMAN ZAPF, the estimable mid-century designer, was inspired to create Optima by the Renaissance-era stone-carved lettering he encountered in Florence. The font is a rare hybrid of sans serif and serif cuts. (Serifs are the decorative lines or strokes at the ends of letters and come in a variety of forms—thin and thick, curved and straight.) Optima reads as a modernist sans serif but the slight swelling on the letters’ ends gives it warmth and nods to its humanist origins. Its formal elegance has proved popular with many designers, including Maya Lin—the names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial are carved in Optima.

Birds-of-a-Type is a regular feature that combines two of my obsessions—birds and typography. It’s a blast for me to design these cards and I hope you enjoy them.

Several have privately asked me how a tall guy can make it work in a VW bug. First, drive is everything when you're a teenager. And I do remember I had to open the sun roof and put it in second gear.

"Here’s why: 1) I live to be incensed..." I do so appreciate this. As they say (unoriginally) You go, girl!