How far would you go?

Self-mutilation in defense of liberty, the inspirations of saints, and a Big Pink revival.

ON LANGUAGE

Extreme devotion: the origins of a popular saying

ONE FRIEND CALLS me Thor, the hammer-wielding Norse deity. I think he means it ironically, since I’m considerably more soft spoken than the Viking thunder god. But I am tall, with blue eyes and blonde hair. On ancestry dot com, I traced one branch of my family to Rollo, the Viking who sacked Paris and ruled over Normandy, and whose great-great-great-grandson William made a memorable trek through England in 1066. Also, according to 23andMe, I’ve plenty of Scandinavian DNA, though the bigger share comes from England and Ireland. That thrusts me, ancestrally speaking, into the geographic dead center of the medieval conflict that gave us the adage about “cutting off your nose to spite your face.” Spoiler alert: The Vikings weren’t the good guys.

Coldingham is a coastal area of Scotland due east of Glasgow and a mere four hundred nautical miles from Norway. Part of the medieval Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria—that is, north of the River Humber—Coldingham was home to an abbey run by St. Æbbe the Younger. Coastal monasteries and abbeys like hers became prime targets of Viking raiders starting in the late 8th century. The most notorious of the early raids began at dawn on June 8, 793, as monks were beginning their morning chants at the St. Cuthbert monastery, on the northeast Northumbria coast. After landing in their longboats, Vikings murdered the monks, looted holy treasures, and took captives to be sold as slaves. Anglo-Saxon Christendom was in shock. Alcuin of York, the Carolingian scholar and clergyman, wrote: “Never before has such terror appeared in Britain… The church of St. Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God.”

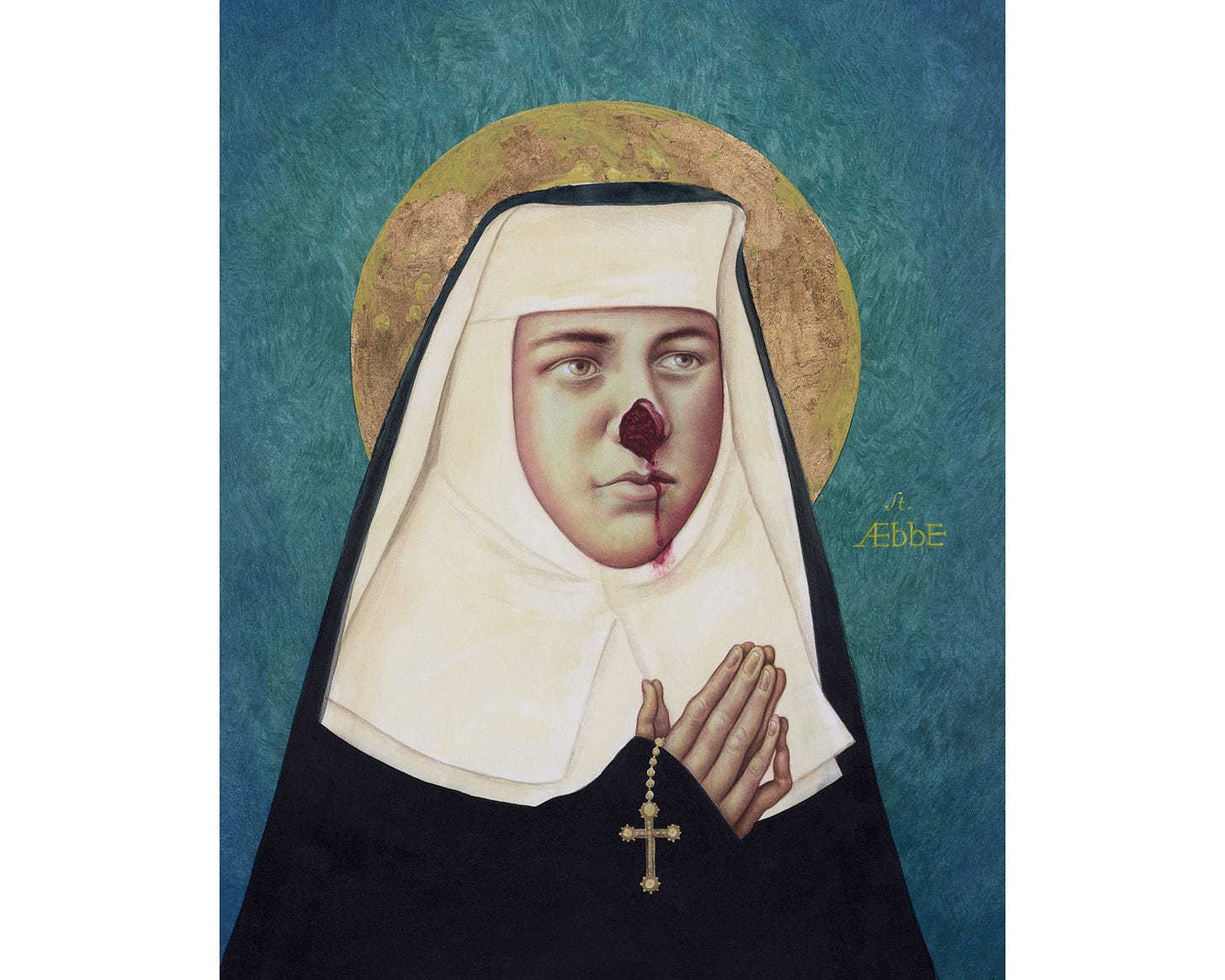

As the attacks escalated in the 9th century, Christians took measures to protect themselves and their religious treasures. None were bolder than St. Æbbe the Younger. On April 2, 870, with the Viking longboats on the horizon, she cut off her nose and upper lip to make herself repellant to the invaders, who often raped their female victims. At her urging, the other nuns followed suit. The raiders were indeed repelled by the sight of the women and, in anger, locked the doors of the convent and burned them to death. Or so the accounts, written four centuries later, tell us. St. Æbbe the Younger was never officially canonized by the Pope, but has been locally venerated since medieval times as a saint, with her feast day on April 2, the day historical accounts record her death. Perhaps more indelibly, her martyrdom is thought to have originated a phrase heard round the English-speaking world. She “cut off her nose to spite her face.”

Yet there’s a problem with this telling. In popular usage, the phrase is deployed to discourage self-destructive acts made in anger. More than once, my mother, like so many others, warned: “Don’t cut off your nose to spite your face.” No doubt, St. Æbbe’s self mutilation did lead to a horrible death. But in fact she cut off her nose to spite the Viking intruders, and her self destruction is viewed admirably as a martyr’s sacrifice—an act of self protection and Christian devotion. It wasn’t pointless, which the current usage cautions us about. The likely explanation is simply that the meaning of many phrases and words evolve over time—12 centuries in this case—often diverging from their original context. We can still admire her sacrifice while keeping our own proverbial noses in their proper place. –Kerry Tremain

The above painting of St. Æbbe the Younger was made by Anita Kunz and is used with her permission. Supremely talented, she is one of the finest illustrators I worked with during my years at magazines. The portrait is from her series of 450 such depictions of extraordinary women entitled “Original Sisters.” An exhibit of the paintings is currently showing at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, through May 26.

Given my obsession with typography, I’d also like to note the the aforementioned Alcuin of York, a key adviser to Charlemagne, is credited with developing a standardized, more legible script, the Carolingian Minuscule, which became crucial to preserving classical texts and improving medieval education.

VIDEO OF THE WEEK

Still carrying the weight

I DON’T REMEMBER exactly when I first heard Music from Big Pink by The Band. It might have been 1968, the year the album came out. At the time I listened non-stop to Detroit’s main rock radio station, WABX, and could have heard it shortly after it was released. Or it might have been the following year, after The Band performed at Woodstock. I do remember that once that album was in the house, I played it over and over and over, in the grip of something I couldn’t name.

This video was produced in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the release of the “The Weight,” a song written by Robbie Robertson, The Band’s main song writer, and first released on their Big Pink album. Listening to this version, the power of the song washes over me again.

Robbie Robertson is front and center on this Playing for Change version. In a 2016 interview, Robertson said the song was inspired by the films of Luis Bunuel about the difficulty of sainthood (just ask St. Æbbe the Younger), and heavily influenced by his memories of his first trip to the Mississippi Delta in 1959 when he was sixteen and directly exposed to the roots of American blues, R&B, and soul. Although Robertson doesn’t mention it in the interview, the song was also clearly influenced by his bandmates, particularly Levon Helm. Levon’s voice was an instrument as essential to Robbie as his guitar—a voice that could combine country and soul in a groundbreaking blend that changed the path of music in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Robbie’s own voice wasn’t good for much more than occasional back-up vocals, but he recognized in Levon a set of pipes from another, higher world.

The other front-and-center musician in the video is none other than Ringo Starr. Who could possibly have lured Ringo into playing on this but a fellow mega-star like Robbie Robertson? Manifesting his signature Liverpudlian whimsy, Ringo starts us off with a joke but manages to keep perfect time throughout the song as the producers bring in performers from Africa, Europe, the Caribbean, North America, the Middle East, South America, and Asia.

In this contemporary version, the principal singing is done by a broad medley of people, a feat of musical engineering. How do the sound engineers at Playing for Change do it? Since 2002, they’ve been making music videos of disparate musicians from around the globe, miraculously blending the sounds from dozens of different performers, studios, and backyard setups. “The Weight” is a prime example of their art.

The singers are as diverse as the settings in which they perform. Marcus King, a young singer-songwriter who follows in Levon’s footsteps, looks like he’s going to sing Grand Ole Opry but instead belts out the blues on the edge of a lake on a hot day in South Carolina. Mermans Mosengo, a gravelly-voiced Congolese singer who’s a regular on the Playing for Change videos, was filmed and recorded on what looks like a random hillside outside Kinshasa. Performing in Trenchtown, Jamaica, Sherieta Lewis and Roselyn Williams each have distinctive and beautiful voices, but together produce an perfectly blended harmony that adds a gospel-inflected note to the recording.

Then there’s Lucas Nelson, filmed in a backyard in Austin, Texas with a rickety porch, a hastily-wound garden hose, and a watering can on a railing. The only thing missing is a dog. That’s okay, because Nelson’s pronunciation of the word “DAWWWG” in the fourth verse supplied me with all the canine I could possibly handle.

Robertson’s melodic, soulful guitar playing dominates the beginning of the song, duplicating the distinctive opening riff in the original recording. That’s perfect for us old-timers, a Pavlovian call to our musical dinner. Here’s a guy in his seventies playing a song he’s played more than a thousand times—ten thousand times?—and is utterly lost in his art form.

Other standout instrumentalists include Ahmed Al Harmi from Bahrain, filmed sitting behind an ornate silver tea seton on a sumptuous-looking couch covered with tapestries. He’s playing the oud, a gourd-bodied, twelve string instrument that was definitely not on the original recording of “The Weight.” His oud and a sitar played by Rajeev Shrestha from Nepal are integrated into the overall sound in a surprisingly smooth way. Yet these distinctly non-American instruments are not a “novelty” feature; they manifest the universality of the song itself.

So please take a moment to open this musical treasure chest. Robbie Robertson, a Canadian man raised by a Mohawk mother, fathered by a professional gambler he never met, wrote an enigmatic song first voiced by an Arkansas farm boy—a song that was international from the day it was born. –Barbara Ramsey

EXHIBITS

PACIFIC NORTHWESTERNERS: Please visit my exhibit, Aves, at the Port Townsend Marine Science Center Gallery, showing through June 8, Friday–Sunday, 12-3. The gallery will be open for Art Walk on the evening of Saturday, April 5, and I will be there to answer questions or just schmooze.

OUR FRIEND Steve Rees has worked tirelessly for years to bring attention to an extraordinary collection of photomontages by the artist Harley Gaber. For Die Plage (The Plague), Gaber reimagined the history of the people and events in his native Germany from the Weimar Republic through the end of the Third Reich. You can now view this monumental achievement online. Steve is looking for additional venues to mount a showing of Gaber’s work, which arguably has contemporary relevance.

Snippets

JAY VALENTINE of Fractal Computing claims we do not need giant new data centers to run AI, let alone half-a-trillion dollars worth. Nor do we need to tear up rural countrysides or build small nuclear reactors to power them. The same work, he says, can be done by 4x4-inch replaceable cubes that use little power and can complete the same tasks in a fraction of the time for a fraction of the cost. Proof of concept was reorganization of the Federal Election Commission database of 680 million records. I leave it to better minds to judge whether this is too good to be true.

IN FIRST FLIGHT, Quentin Hardy warns that current AI systems, built on imitations of language, echo the mistakes underlying Clément Ader’s failure to beat the Wright Brothers. Though he carefully imitated the flight of birds, Ader’s creation could not fly. AI is built on Large Language Models, which, like language itself, cannot truly imitate life. And by the way, Meta is training its LLMs on huge quantities of copyrighted material without permission. Want to see if your stuff is included? Search here.

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF, Canadian philosopher and former leader of the Liberal Party, writes in The Cost of Betrayal that the damage to America’s foreign alliances is irreparable. These alliances were built on a trust established over decades and cannot be replaced.

IN THE FACE of Trump’s withdrawal of support for Ukraine, the European Commission has launched an 870 billion-dollar military rearmament. It may give a Keynsian boost to European economies—think of troubled Volkswagen building military vehicles—but the effort will serve to centralize power in the European Commission. For that reason, Thomas Fazi argues that the move is anti-democratic as well as more likely to lead to confrontation with Russia, whose aggression is ironically the rationale given for rearmament. A massive military buildup in Europe—what could go wrong? I’m reminded of the Tom Lehrer song where he sings of the Germans, “We taught them a lesson in 1918 and they’ve hardly bothered us since then.”

THE VICIOUS CIRCLE that incentivizes urban homeowners to resist any change that might depreciate their biggest capital investment, and renters to resist neighborhood improvements to prevent rent increases, makes cities less productive and leads to a cascade of social problems. Could broad-based fractionalized real estate ownership—similar to REITs—lead us out of this trap? Chris Lehman thinks they could help improve cities’ productivity, civil life, and governance.

SMALL AND MEDIUM firms make up an amazing 98.6 percent of manufacturing in the United States, employing 2.6 million workers and propping up many local economies. Over six in ten are owned by baby boomers and four in ten of them have no plans for succession. Without government intervention, says Garphil Julien, they are ripe for takeovers by private equity, whose motivation is often to extract as much short-term value as they can and then shut them down. Employee Stock Ownership Plans are only part of a possible solution.

POSTSCRIPTS

A SHOUTOUT to our niece Tamra and her two daughters, Trinity and Anna, who saw a grass fire approaching the nursing home in their tiny town of Yates Center, Kansas. Before firefighters arrived, they rushed in to help staff evacuate the two dozen residents, through smoke and flying embers. The home burned, but all were saved. Anna, who is sixteen and worked part-time at the home, stayed with the residents when they were taken to another town for temporary shelter. She also had the foresight to rescue the cart with the residents’ meds. Trinity had a moment of panic when she returned to her car and found it missing, along with her wallet, phone, and keys. But all was well. A neighbor had seen it parked close to the fire and driven fleeing residents to safety.

THE SAYING, favored on detective shows, that “there are no coincidences,” has become spookily true as our searches and social media posts are relentlessly poured over by bots and their content shared with sellers’s bots, so that “related” products can be pitched back to us. I got the above card, the first in a very long time from my alma mater, delivered by the post office, on the very day that I posted my story about William Jewell and Jesse James. Coincidence? Well, yeah, probably. –KT

WE WERE PLEASED and amused when Diane Wheatley, who sent us the postcard with ten sayings from her native Lancashire, admitted she’d (finally?) learned what a couple of them meant from reading our Wild Things post.

I was a pop fangirl in the 60s thru the 80s, so came late to The Band. When I discovered the video you shared, I just couldn’t get enough of it, played it over and over and OVER. It inspired me to donate monthly to Playing for Change. The Weight feels so dream-like to me, and if I just listen/watch it one more time, I’ll be able to interpret it. Thank you for highlighting it!

I could not resist to say a few words in regard to "The Weight", The Band, and Playing for Change. Of the songs that are the soundtrack of my life and the ones that I have told my wife to play at my funeral, "The Weight" is number 2, right behind "Ripple" by the Grateful Dead which is number 1 on the list. It's no secret as many of the readers of Wild Things know, the Grateful Dead has and is a major part of my life and influences. In fact one of my latest series of photographs has been inspired by the words, the music, the art, and the iconography of the Dead! The Band, and the many of the other amazingly talented wordsmiths and musicians have also been a part of that soundtrack of my life, and I'm grateful to them all. But my first exposure to Playing for Change just happened to be my number 1 pick, "Ripple", and yes, I cry each time I hear and see it. (You can see and hear it here. https://playingforchange.com/videos/ripple-song-around-the-world) In these difficult times organizations like Playing for Change and the songs from the soundtrack of our lives can give us all hope for a better future for humanity as a whole. "Let there be songs to fill the air".