Cherokees, Chemakum, and Chomsky

Language is acquired, a tribe is affirmed, and ampersands are celebrated. Plus: the price of humiliation and the tragic necessity of pluralism.

WHAT’S BARBARA THINKING?

How could language be?

By Barbara Ramsey

HOW IN THE HELL did a few moderately successful primates ever come up with language? It wouldn’t be credible except for being so commonplace. How, in all its complexity and flexibility, could it have come about?

And I mean exactly that: how could it—not how did it—come about. The “how did” part is explicable. Almost all multicellular organisms manage some kind of communication, even if it’s just a conversation between one body part and another. Peter Godfrey-Smith, an Australian philosopher of science and avid scuba diver, gives the example of a shrimp with long feelers he observed. While feeding, one of the shrimp’s feelers accidentally grazed its mouth. The shrimp began to eat itself and then immediately retracted the feeler. Its nervous system telegraphed “Ouch! Don’t eat this!”

Once vertebrates began to live in the air rather than water, vocalizations traveled easily. Our ancestors chittered, chirped, grunted, and bellowed their way through the world, generating a positive feedback loop of sound-generating and sound-receiving systems that became ever more complex. Evolution’s driver is reproductive success and those creatures whose communication tools promoted more efficient reproduction were favored. Primate groups that hunted cooperatively captured more game and more nutrients.

The “how could” part is more baffling. Perhaps future neuroscientists will discover a mental substrate that enables language to develop. We aren’t simply Skinnerian creatures who are positively reinforced for imitating the sounds around us. I’m convinced of Chomsky’s hypothesis that we possess an innate capacity for language, enabling us to deploy this mighty tool without much effort.

Language systems are composed of a huge variety of sounds, called phonemes, which vary across the world. English has a middling number of phonemes, about forty, while Spanish has only half as many. The Taa language, spoken in Botswana and Namibia, is thought to have almost two hundred. Some languages combine musical tones with spoken syllables. Languages with clicks, unless learned by age thirteen or fourteen, are rarely mastered. And these are just drops in the linguistic ocean.

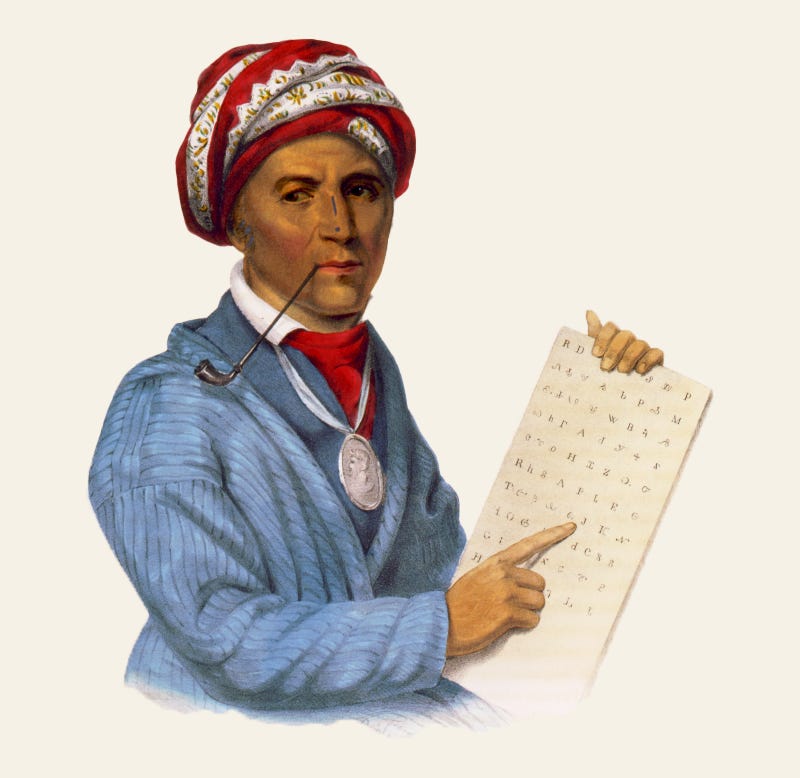

Then there’s written language, at least 5,000 years old and probably older. Still, scholars estimate that only about fifty percent of known languages have a written form today. Nothing in our primate lineage requires us to write, but we do. And we do it a lot. It’s so useful that people without a written language can adopt one quickly. The Cherokee leader Sequoyah invented a written form of Cherokee over a twelve-year period and it remains in use today.

Sequoyah was monolingual in Cherokee. He knew English speakers had a visual representation of their language, but he was unable to speak, read, or write it. He began to create his own writing system in 1809 by carefully analyzing the Cherokee language spoken all around him. He composed a syllabary—in which written symbols represent whole syllables—rather an alphabet, supporting the evidence that he didn’t use English as a template. His whole story resembles a fairy tale. By some accounts, a group of tribal members even suspected he was sending messages through witchcraft, not marks on paper. Ultimately, his written form of Cherokee spread quickly and was formally adopted by the tribe in 1825. And sure, the guy who came up with it was a genius, no doubt. But once he’d figured out the basics, he taught it to his six-year-old daughter, A-Yo-Ka, who helped him finish the syllabary. This tells me that we’re wired not only to speak language, but to convert it into visual symbols if given the slightest encouragement.

Knowing this comforts me, especially when I feel compelled to finish this little essay rather than all my unanswered emails, unsewn quilts, and unfinished taxes. I’m only a primate, after all, one driven to speak and to write by a brain beyond my control.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Still here

“THE CHEMAKUM. Massacred. Extinct. Terminated. Administratively removed. Written out of History. As a tribe. As a People.”

So begins the book Still Here by Rosalee Walz, with photographs by Brian Goodman. The book—and the exhibit of the same name—began during the pandemic when I joined an online meeting of a group called Native Connections at the Unitarian Universalist fellowship. I had read, in online references and books on the subject, that the Chemakum people, who lived on the peninsula where I live now, were extinct. And then I met several of them.

After attending these meetings for a few months, I proposed that one way to help reverse the “disappearance” of the Chemakum was to photograph them. Tribal members enthusiastically embraced the idea. I enlisted my friend, Brian Goodman, and at a tribal gathering in a nearby park in the summer of 2021, we did just that. Brian brought a trailer full of equipment and we set up an outdoor studio next to the pavilion where they were gathering. Using a medium-format camera, he took a series of remarkable portraits, most of them individuals as well as a few couples and families. The ages ranged from five to eighty-five.

The following April, we exhibited the photographs, printed over five feet tall, in the high school in Chimacum—named after its original inhabitants. I designed and produced the book with Rosalee, who led the ceremony at the high school. Despite a new Covid surge that spring, over 250 people attended the opening, including county supervisors, and city council and school board members. We had about seventy-five books and sold all of them.

Towards the end of the that event, two members of the Quileute tribe arrived from the coast, where they have a reservation. With them were a married couple: Jay Powell, a linguist, and Vicky Jensen, a photographer. I had met them while working on a story about a leader of the Nuu-cha-nuth (formerly Nootka) people who they helped develop a tribal dictionary and language program. Now the two were working with the Quileute. I’d not seen them since 2002.

The Quileute and the Chemakum share a language. They are the oldest inhabitants of the northern Olympic Peninsula, according to Powell and others, and there are different accounts of their geographic separation. One involves a great flood where “the canoes were in the trees”—possibly a tsunami. Many of the Chemakum were killed by other tribes in the mid-19th century and later administratively excluded by federal agents. Fortunately, Columbia anthropologist Franz Boas recorded enough of the language in 1890 from a few remaining Chemakum speakers to establish the linguistic connection with the Quileute. At the April event, the Quileute representatives sang songs in their shared language, offered gifts, and welcomed the Chemakum as tribal brothers and sisters.

This overdue recognition, just for existing and carrying on their traditions, opened up new opportunities for the Chemakum. In the ensuing months, they established a nonprofit and elected tribal leaders, with Rosalee as chair. She and others began studying the language alongside Quileute tribal members in a course taught by Powell. One of the Chemakum is seeking land and funds to build a longhouse. The historical signage at the nearby state parks has been changed to acknowledge them. They launched a web site. And they are working to secure a cedar log and artisans to carve a canoe for the summer journey that has become one of the major Native American events in the northwest.

Brian and I, too, have reaped rewards: A friendship with Rosalee and other tribal members. An honoring and blessing from the tribe. And a restored faith in the power of photography and art, every now and again, to change things.

An exhibit of the Still Here photographs will be shown at the Quimper Unitarian Universalist Fellowship in Port Townsend in March and April. To support the tribe’s initiatives in language restoration, canoe carving, and other projects, please make a donation.

Postscript

THE STORY I wrote about a leader of the Nuu-chah-nulth—closely related to the Makah on the Olympic Peninsula—is available at kerrytremain.com. Andrew Callicum worked over decades to revive the language and potlatches of his First Nation. I was inspired to write about Callicum when he was killed in a tragic accident. I attended the potlatch honoring him on Vancouver Island with friends from Native American Health Center in Oakland, where he worked as a counselor. The story begins:

Among the native people of Vancouver Island, your name, especially if you descend from a line of chiefs, tells a story. You learn to sing your name and dance the family legends, correctly, at the many feasts held in winter months. If you dance as Bear, you fatten your swagger. You sniff the air. You jerk your terrifying eyes toward your prey. Your name often recalls an ancestor’s encounter in the woods with a supernatural being such as Kwatyat, the trickster, or Tl’ihul, the Thunderbird. (Although they would never be called “supernatural”; to you, they are as real as your grandma.) The name may tell a joke or boast great feats (“Ten Whales at a Time”), or both (“Always Copulating”). . . Read more.

EXHIBITS

NOTE TO READERS: A gallery recently returned a limited number of prints from my Outside In exhibit last summer and I’ve put them on sale at substantial discounts. For most, only a single print is available. Some are framed. To see the pictures, click here.

THIS IS THE FINAL week to see Linda Okazaki’s magnificent retrospective, Into the Light, at the Bainbridge Museum of Art. Also closing soon are the Northwind Art Burst of Color exhibit with two of Barbara’s quilts, and the CVG Washington state exhibit in Bremerton, where my photograph, Red-tailed Tropicbird, won a prize. Okazaki’s book from her exhibit can be purchased through the BIMA bookstore.

FOR THE LOVE OF TYPE

I’VE NEVER KNOWN a graphic designer that didn’t like an ampersand. Oh, there were probably a few from the nothing-but-Helvetica era that was winding down just as I was getting started in the mid-’70s. Roger Black’s Rolling Stone helped open things up, as did Herb Lubalin’s U&lc with its epic ampersand. Engraved in wood by Louis John Pouchée in London in the 1820s, this florid ampersand fortunately survived a fire at the Monotype Corporation headquarters in 1940. Pouchée produced the most ambitious and largest collection of wooden-type alphabets from the period.

Snippets of the week

Isaiah Berlin on the inevitability of clashing values and pluralism as a response. “We must weigh and measure, bargain, compromise, and prevent the crushing of one form of life by its rivals. I know only too well that this is not a flag under which idealistic and enthusiastic young men and women may wish to march—it seems too tame, too reasonable, too bourgeois, it does not engage the generous emotions. But you must believe me, one cannot have everything one wants—not only in practice, but even in theory. The denial of this, the search for a single, overarching ideal because it is the one and only true one for humanity, invariably leads to coercion. And then to destruction [and] blood….” —Quoted by Damon Linker in Persuasion.

Reflecting on Li Zhensheng’s photographs from Mao’s Cultural Revolution. “Are punishment and humiliation simply a variation on a theme? I would argue that, on the contrary, they are antithesis. Punishment based on the rule of law can be the ally of justice, but cruelty and humiliation cannot. Nonviolent punishment—at least when done right and directed toward the guilty—seeks to reconstruct a moral order that has been disfigured by unjust deeds; humiliation, conversely, attempts to destroy the wrongdoer’s self worth, create pariahs, and solidify a community on the basis of contempt.” —Susie Linfield, The Cruel Radiance

Ooh, all this reading about words and language has given me a tingle. Thanks Barbara, for your essay diversion from tasks at hand. These successful primates can be quite amazing.

Thanks Kerry for the additional information on the Chemakum. I am still learning much about our neighbors on the Peninsula. This opens so much more to absorb.