Basques to the west, Nazis to the east

On John Muir's disgust and a Latvian grandmother's surprise. Plus Sabon Swans.

YOSEMITE AND THE HISTORY OF THE WEST

Basque sheepherders of the west

IN 1923, THE YELLOWSTONE prequel starring Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren (ah, Helen), Ford plays a cattle rancher, Jacob Dutton, who is ambushed and nearly killed. Others in his party don’t make it. The murderers are led by a sheepherder. In this age-old story we’re on the side of the Duttons. Cattle ranchers are the good guys and nomadic sheepherders are the bad guys. Same as it ever was.

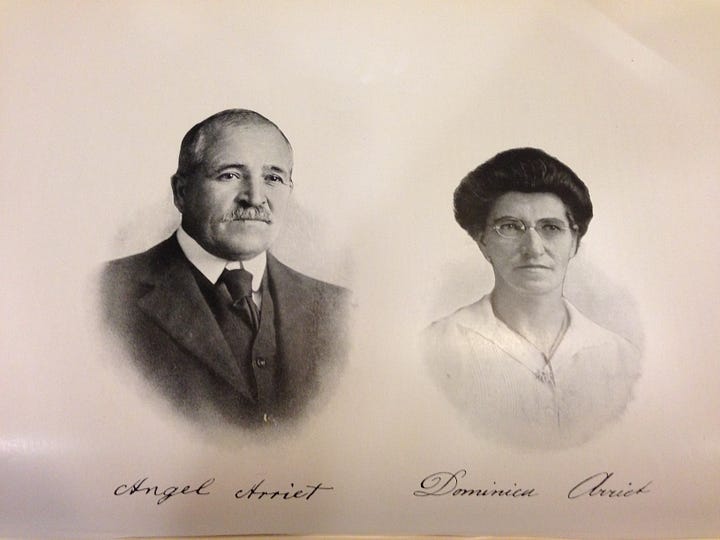

Many of those sheepherders were Basque. They are the oldest known indigenous group in Europe and speak a language unrelated to any other. Paul, one of my close friends, is of Basque heritage and I have been to their historic homeland in and around the Pyrenees mountains of southwestern France and northwestern Spain. When you arrive at the airport in Biarritz, France, the sign on the terminal welcomes you to “Pays Basque”—Basque Nation. Paul still visits his uncles and cousins there—one restored the family’s 17th-century stone farm house—and some are still agitating for an independent Pays Basque.

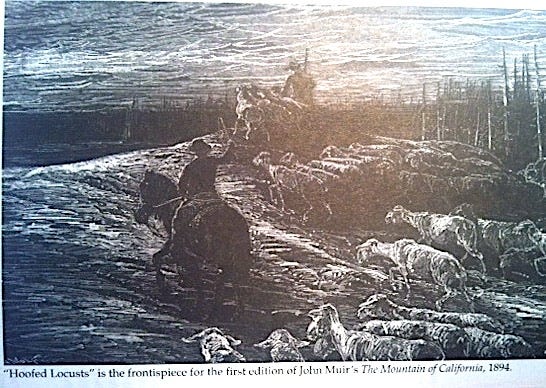

John Muir called the sheep “hooved locusts” and helped rally the Army to banish the sheepherders from Yosemite, where they pastured their flocks in meadows below Mt. Dana. Long vilified in official histories, the sheepherders are now thought to have played a positive environmental role in the park. The small fires they burned to create meadows for grazing —like those used earlier by Ahwahneechee to cultivate their acorn forest—helped prevent catastrophic fires.

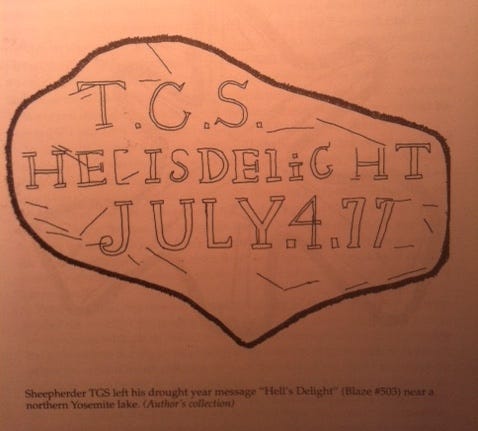

In Yosemite and elsewhere, the Basque herders invented their own language comprised of arborglyphs—symbols and letters carved into the bark of lodgepole pines and aspens. One park historian recorded over 1700 of them and there are tours of arboglyphs in California, Nevada, Idaho and Oregon. Their coded communication helped the shepherds evade the Army patrols and was a balm for their isolation.

Paul’s great grandfather and his three brothers emigrated to the United States in the 1860s. After working as herders, they acquired a ranch near Salinas that eventually expanded to 5,000 acres. Like others who came in the late 19th and early 20th century, they were young men looking to make some money. They were aided by a network of Basque hotels, called Ostatua, that criss-crossed the country. At dockside, the men were greeted in their language, a comfort after a long journey on a cargo ship, and given a place to stay. But sheepherding was a lonely life, different from the one back home, and the many weeks and months alone took a toll. Over a third eventually returned to Europe with whatever money they had saved.

The range wars also took a toll. Like the fictional Duttons, cattle ranchers fought sheepherders with barbed wire, guns, and political power. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, which restricted grazing on public lands, was a devastating blow. While it helped address overgrazing on public lands, the local distribution of parcels was controlled by ranchers. The government welcomed the Basque sheepherders back, however, when the Army needed wool for uniforms and blankets during WWII. Paul remembers his grandfather bringing whiskey and fruit to the Basques tending huge herds at Fort Ord on Monterey Bay.

Large Basque communities in Idaho and Nevada still celebrate their heritage in annual festivals of song and dance featuring traditional foods. A few of the old Ostatua remain. Some, Paul tells me, welcome everyone for food and drink, but to rent a room, you must prove you’re Basque.

Editor’s note: We included several of the arboglyphs in the exhibition, Yosemite: A Storied Landscape, that I co-curated at the California Historical Society. Roosevelt’s Farm Security Administration (FSA) generated documentary photographs of the Basque sheepherders, including a 1940 project in Nevada by Arthur Rothstein. Below is a slideshow of some of those pictures. A historian of the FSA photographers, Carl Fleischhauer, along with my friend Bill Smock, photographed Nevada sheepherders some forty years later in conjunction with their film, Buckaroos in Paradise.

A friend also recently unearthed this postwar series on the Basques that Orson Wells produced for BBC. Each segment is about ten minutes; here’s Part 1 of 6:

TALES FROM THE CLINIC

A Latvian grandmother’s surprise

By Barbara Ramsey

IN MY THIRD YEAR of medical school, I undertook a difficult six-week surgery rotation. I was delighted to find my old friend Tom assigned to the same rotation. We’d shared a cadaver during the first year of medical school. Amidst the acrid smell of formaldehyde, we’d cracked a lot of bad jokes.

“Barb! Oh my god—this is perfect,” he said when he saw me standing at the nurses’ station. “At last we get to cut open living people.”

The first week, Tom introduced me to one of his patients, Mrs. Jacenas, who was especially sweet. One day, I helped him change the dressing on her surgical wound and chatted with her to distract her from the yanked tape.

“Ah, you are so good to care for me. How could you both be doctors, both so young! Mazulis, only little ones.” She was in her late sixties, with large blue eyes and a thick head of blonde hair streaked with white. Her favorite topic was Latvia, which she had fled in 1945 when the Soviets invaded. She hadn’t seen her beloved homeland for almost thirty-five years but still considered herself a refugee.

As a child I’d been hooked on a collection of Baltic folktales—stories from Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia. People searched for special trees growing in the middle of the ocean, magical axes warded off evil, and wizards transformed themselves into animals. The purple binding and those embossed letters on the cover became talismanic to me. And here was a Latvian grandmother, in person!

Tom and I both loved to hear her talk about the wonders of Latvia. “Ah, we have the freshest fish, the best dancing, the sweetest choirs,” she enthused. “I miss all of it.” We also heard about Seattle’s Latvian community group, in which Mrs. Jacenas apparently played a large role. They had their own church, sponsored cultural events, and ran an after-school program to teach their American children to speak proper Latvian.

Her wound was healing nicely and right before she was discharged, she told me and Tom she’d like to repay our many attentions by treating us to a special event—Jani, the Latvian summer solstice celebration. “It will be in two weeks. There will be so many young people there, young people like yourself.” She was excited. “You can see our beautiful traditions. You will like it,” she insisted.

Tom and I said that we would come if we could, but I was a bit ambivalent. I’d been raised in a city with lots of ethnic festivals: Polish polka contests, Ukrainian egg decorating demonstrations, and Greek Orthodox carnivals. Some were fun, some were not. “Oh come on, Barb, it’ll be great,” Tom said. “When will either of us ever get a chance to visit Latvia?” He was right. Who knew what could happen at a summer solstice festival? It sounded suitably pagan and might even surprise me.

Little did I know.

On a lovely day in June we arrived at the Latvian community center and found a spacious building decorated with wreaths and tree boughs. Mrs. Jacenas immediately came to greet us. “Oh my little doctors, so good of you to come! Come in, come in, take these seats.” She motioned to some chairs directly in front of a large stage and then sat next to us.

The first group to perform was a chorus of thirty people dressed in elaborately colored traditional costumes. The women and girls wore headdresses with flowers and herbs artfully perched on their heads and long skirts down to their ankles. The men and boys wore white shirts and baggy trousers. They opened their mouths and—how can I convey this?—it was celestial. Their choral tradition includes songs with intertwined polyphony, unexpected and lovely. They sang a Jani song with a soaring melody in perfect harmony, a beautiful Baltic stairwell of sound.

The choir was followed by a young folk dancing troupe. Slim, blond, tall, and athletic, they looked like an advertisement for a Scandinavian river cruise. Their homemade peasant garb was gorgeous and well tailored—Sound of Music quality. All three traditional dances were beautifully choreographed and executed.

But the finale shocked me. The dancers reappeared dressed in modern garb, looking exactly like the Swedish pop group, Abba. I’d been lulled into fantasies of picking flowers on a Latvian hillside. Now, I was seeing elaborately made-up girls in satin outfits that revealed lots of leg and cleavage. The boys wore skin tight pants and pointed colored boots.

They could have opened for Elvis in Vegas. They gyrated, they leapt, they became entangled in provocative ways. After they’d taken their final bow, Tom and I looked at each other, stunned. Mrs. Jacenas stood up and announced, “Now, we eat!”

She led us to a row of tables laid out with smoked fish, fresh homemade rye bread, exotic cheeses, savory pastries with bacon and onions, and kegs and kegs of beer. Tom and I indulged in all of it . When we couldn’t stay longer—our studies called—we found Mrs. Jacenas and prepared to say our good-byes. We thanked her for inviting us.

“I understand, dear ones. You have work to do. But it makes me glad to know you have seen a little of my people,” she said. “We are strong and will one day return to where we have come from. We will drive away the bear!” I knew she meant Russia. “Our beautiful youth will see Riga, like when I was young and the Germans freed us from the bear’s yoke.”

The Germans? What could she possibly mean? After the Germans invaded Riga in 1941, they occupied the country for four years, committing unspeakable crimes. At the war’s beginning, more than 80,000 Jews lived in Latvia. By war’s end there were fewer than 2,000.

“Do you mean the Nazis?” I stood there, incredulous.

“Ahh they weren’t so bad for Latvia.” Her voice was level, matter-of-fact. “You Americans don’t know but the Germans did many fine things for our people.” She meant the Gentile Latvian people. That’s all she’d ever meant. My adopted Latvian grandmother was a Nazi-lover.

My head throbbed and it wasn’t the beer. She beamed, smoothed her skirt, and gave us one last smile as we hustled out the door.

BIRDS-OF-A-TYPE CARD SERIES

Sabon swans

TRUMPETER SWANS winter in Washington’s Skagit River valley alongside tens of thousands of snow geese. On a bitterly cold day, my friend Tim and I stopped by the side of one of the valley’s crisscrossing farm roads when we spotted a large field of the swans. Every minute or so, small groups took off and made ten-mile circles over the area before returning to the field. I must have looked like a spinning top as I swung around time after time to photograph the swans in flight.

SWANS REPRESENT classical beauty and Sabon represents a classical revival. Sabon was created by Jan Tschichold, one of the great type designers of the 20th century. Early in his career, he was an exponent of modern sans-serif typography, often associated with the Bauhaus. In 1928, he authored Die Neue Typographie—The New Typography—a book that heavily influenced contemporary design. Five years later, the Nazis deemed his work “cultural Bolshevism” and arrested him. Upon release, he fled to Switzerland, where he lived the remainder of his life.

Tschichold developed Sabon late in his career, after he had moderated his earlier views and embraced classical designs. The font is named for Jacob Sabon, a 16th-century Frankfurt printer who developed a type system that Tschichold deployed four centuries later. Sabon was introduced in 1967, seven years before he died. In the 1990s, I chose it as a principal typeface for a redesign of Mother Jones.

Birds-of-a-type is a regular feature that combines two of my obsessions—birds and typography. It’s a blast for me to design these cards and I hope you enjoy them.

Kerry, thanks so much for the Orson Welles bits on the Basque Country...At least half of the episodes were filmed in the family village of Sare which lies a few short kilometers from the Spanish border. A frontier the Basque people refuse to recognize. Zazpiak Bat

Hi, Barbara. I wasn't surprised at the ending of the Latvian story. I helped a friend publish a memoir of his mother's about her life in Lithuania during WWII. First the Russians came and stayed for one year, then the "Christian" Lithuanians showed up at their house in advance of the Germans. She never saw her father or brother again. After surviving the ghetto, she was sent to Dachau where, incredibly, she met her future husband. They both survived the camp, came to Chicago and got married. You can order the book here, if you're interested. https://www.lulu.com/shop/sonja-haid-greene/between-life-and-death/hardcover/product-17g8m947.html