PERSONAL HISTORY

Mother’s days

A FEW YEARS BEFORE she died, I returned with my mother to her family home in West Virginia’s eastern panhandle. Amongst the boutique inns and organic restaurants catering to DC-area professionals, remnants of the old life can still be seen if you know where to look. George Washington called the town Bath for its hot mineral springs. It’s now named Berkeley Springs. Gettysburg, Manassas and other battles were fought nearby, and a memorial in the town square carries the names of fallen soldiers from that war and those since. Many have my family's surnames—Householder, Butts, Stanley, McCullough. Across the street from the memorial, a tiny museum displays labels from long-gone small-farm canneries, including my great grandfather's tomato-can label. They are ghosts of a way of farm life that was practiced for centuries and all but disappeared in a few decades.

My mother’s family largely consisted of northern Rhineland Protestants who landed in Delaware beginning in the 17th century. Even the Irish McCulloughs were “Orange men”—Protestants—my Uncle Elwood told me as I stood in front on one of their tombstones. These ancestors crossed into southern Pennsylvania, attracted by Quaker John Penn’s well-known religious tolerance. (Quakers were also pacifists—one of my ancestors was excommunicated for joining Washington’s army.) My relatives settled the area at the intersection of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland—West Virginia only separated from Virginia and the confederacy in 1863. Settlers carved their small farms from the low hillsides, cleared stands of timber, and raised apple trees, garden vegetables, pigs, chickens, cows and horses.

When my mother was a girl, she helped pick and core the apples, fed the chickens, fetched entrails from the barrel placed under butchered pigs and cows, and stirred the huge iron pot used to render their fat. Although I lived briefly on a farm—and for a time attended a one-room schoolhouse with boys and girls outhouses—I’ve never so much as wrung a chicken’s neck.

During the Great Depression, my mother and her family, like so many others, were forced to leave the farm for the steel mills or anywhere my grandfather could find a job. Over the following decades, a way of life stretching back to the river bottomlands of Europe was broken. Mom left home when she was sixteen, for San Francisco. Our own family moved several times, too, but in each new place she would seek out the local farmers to collect fresh eggs and garden vegetables. When I was old enough, she taught me to cook the meals she’d known as a child. I've still never butchered an animal or even raised my own vegetables. But I appreciate those who still do and I can cook the old dishes, which helps keep some part of her alive.

TALES FROM THE CLINIC

Snack time

By Barbara Ramsey

I ALWAYS CRAVED sweets during my long afternoons at the clinic. Our work was often frustrating and our patients complicated. To compensate, all of us—receptionists, nurses, medical assistants, doctors, outreach workers—held frequent potlucks and staff birthday parties to reward ourselves with food. We used any excuse to fill the break room with goodies. Many on my staff liked nothing better than a hot piece of fry bread with all the toppings. I enjoyed that, too, but for me, dessert was the thing. My favorite bakery was a Just Desserts store in Oakland. They made a Kahlua cheesecake that I especially loved, and I made sure all my friends knew it was my favorite.

One morning, Sue, a co-worker I liked, left the clinic early to attend a noon baby shower. She promised to make up for her early departure by bringing back leftover food from the event. Good deal, I thought.

Shortly after lunch, Sue returned and as promised presented me with a generous hunk of cheesecake. It was beautiful—the exact shade of caramel that only Just Desserts could achieve by adding the right amount of Kahlua. I was busy with patients and didn’t have time to eat it then, but the vision of that cake stayed in my head all afternoon. It kept me going for the next several hours as I went from exam room to exam room. Finally, around four o’clock, I had a few extra minutes and returned to my desk. The creamy looking wedge of cheesecake sat there, just as I remembered. My wait was over. I grabbed a fork and plunged a big chunk into my mouth.

F******k! It was putrid. Truly horrid. I involuntarily spewed it out of my mouth and by the merest of chance it landed in my large, government-issue garbage can. This can had probably been serving its country since World War II and continued to perform well that day, perfectly catching the foul projectile. Relieved that I hadn’t spewed onto the floor, I scraped the rest of it into the can. I wanted my desk to be free of every last trace of… what? What the hell had I just tasted?

Still, I knew Sue was bound to return any minute to ask me how I liked it. And the evidence of my opinion conspicuously stared back at me from the garbage can. I hastily grabbed some junk mail, threw it on top of the food, and shoved the can under my desk just before she walked in the door.

“So how’d you like it?” she said. “Pretty amazing, huh?”

“Oh wow, yeah, really amazing.” I struggled to keep my composure. “Do you know how it was made?” Sue, I knew, was a cook and a bit of a health food nut.

“Well, you’re never gonna believe it. There weren’t any dairy products in it, and no sugar either,” she said. “The whole thing was made with tofu and rice syrup and seaweed products!”

I looked directly at her and spoke the simple truth. “I’ve never had anything like it,” I said, and she left my office, smiling.

FOR THE LOVE OF TYPE

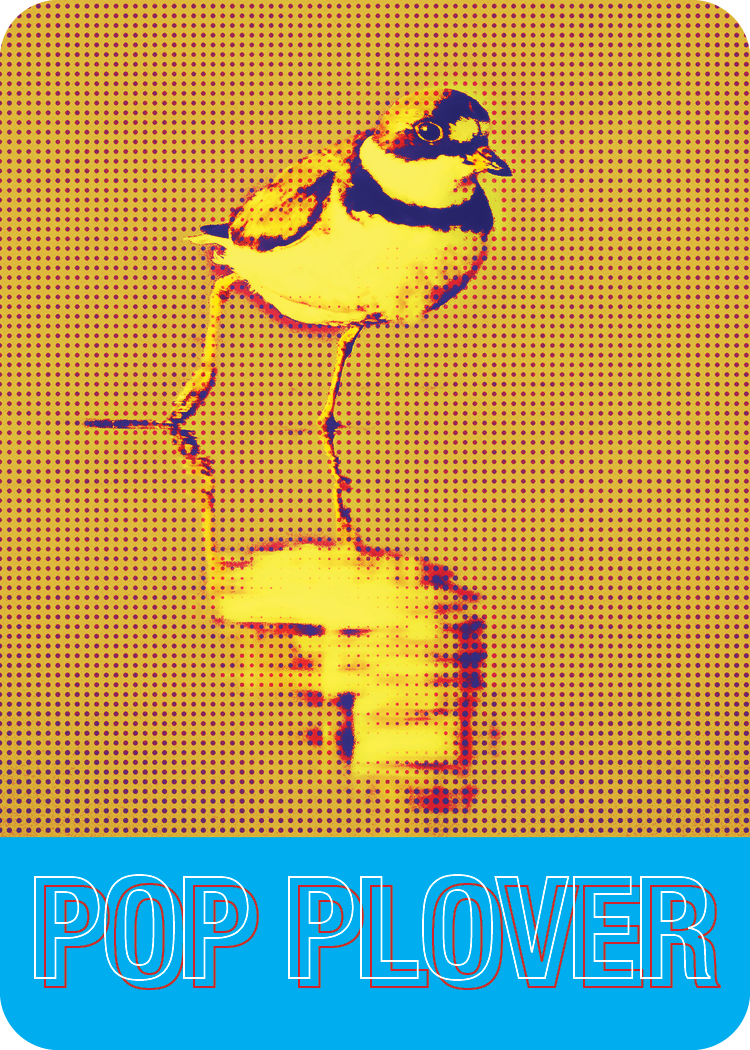

Pop plover

POP PLOVER is the new card in my Birds-of-a-Type series. The typeface is Helvetica, of course, designed by Max Miedinger and released by Linotype in 1957. The world has not been the same since. I took up graphic design in the 1970s and remember going to a design show in Chicago—a birthplace of modernist design—where every single entry used Helvetica, including the 9-point texts in narrow columns. Helvetica became the face for nearly all public signage. There’s even been a movie made about it. My bird card uses Neue Helvetica, redesigned and released in 1983 —in fifty-one versions—reportedly to improve the original face’s legibility and adapt it for the new photo-type machines. The bird is of a more ancient vintage, a Semipalmated Plover, photographed during the spring migration in Ocean Beach, Washington.

THE SALE CONTINUES. I’m down to the last couple boxes of Aves. Take advantage of this special price to land a perfect gift for a bird-loving friend—or for yourself!

“Evocative, mysterious… the work of a true master.” –Bill Curtsinger, veteran National Geographic photographer.

IF YOU LIVE or find yourself in Portland this year, please check out my collection at the Blue Sky Gallery, 122 NW 8th Avenue. You can also find my book and cards at the Jeanette Best Gallery in downtown Port Townsend, Washington.