You say you want a revolution

Riffing on hummingbirds, rooting out the capitalist pig, and fishing for the right word. Plus: a mid-air flamingo rescue

BIRDS

Flying hearts

WITH BARBARA’S surgery on the horizon, we’ve become attuned to the heart’s depiction in story and myth and song. Knowing that, a friend dropped off this essay, “Joyas Voladoras”—”joyous flyers”—by Brian Doyle, published a decade ago in The American Scholar and in his collection of essays and poems, One Long River of Song. The essay begins with an extended meditation on hummingbirds.

A HUMMINGBIRD’S HEART beats ten times a second. A hummingbird’s heart is the size of a pencil eraser. A hummingbird’s heart is a lot of the hummingbird. Joyas voladoras, flying jewels, the first white explorers in the Americas called them, and the white men had never seen such creatures, for hummingbirds came into the world only in the Americas, nowhere else in the universe, more than three hundred species of them whirring and zooming and nectaring in hummer time zones nine times removed from ours, their hearts hammering faster than we could clearly hear if we pressed our elephantine ears to their infinitesimal chests.

Each one visits a thousand flowers a day. They can dive at sixty miles an hour. They can fly backwards. They can fly more than five hundred miles without pausing to rest. But when they rest they come close to death: on frigid nights, or when they are starving, they retreat into torpor, their metabolic rate slowing to a fifteenth of their normal sleep rate, their hearts sludging nearly to a halt, barely beating, and if they are not soon warmed, if they do not soon find that which is sweet, their hearts grow cold, and they cease to be.

PERSONAL HISTORY

Slaying my inner pig

DURING MY FIRST summer in California, I divided my time between looking for a job and listening to the Watergate hearings on television. The hearings were riveting, the job search dispiriting. The economy was in poor shape and my recent degree in philosophy and psychology from a Baptist college in Missouri impressed no one. I did manage to get an interview for a job as a counselor in a summer camp. Fifteen minutes in, the interviewer, a guy with long hair in shorts and sandals, said, “I’m not going to hire you. Do you want to know why?” I nodded. “You’re not in touch with your feelings.” I left feeling insulted and worried he might be right.

The following year, in 1974, I joined a “Radical Therapy” men’s group. Twice a week, a dozen of us sat cross-legged on a weathered carpet in a weathered but lovely Berkeley brown-shingle home off Telegraph Avenue behind the Co-op (now a Whole Foods store). The sessions ran at least an hour and must have been cheap. My new job with a publishing collective paid twenty-five dollars a week.

We revered our counselor, though he strived to convey that we were all equals. The sessions were guided by a philosophy based on the pop-psych notion that our “inner child” could be revealed and transcended through therapy. Radical Therapy’s innovation was to focus instead on our “inner pig”—the poisonous concoction of capitalist, paternalist, and racist ideas taught by society that live inside us. Whatever mental issues we might have, such as depression or anxiety, would presumably diminish or vanish once we slaughtered our inner pigs.

I eagerly attended these sessions for six months. I’d never been in therapy before and found talking about feelings, any feelings, new and thrilling. But when I began to think of my “inner pig” as a thing physically lodged in my chest, a demon to exorcise, a red light went off in my head. Treating neurosis as an actual thing—a reification—was exactly what I’d concluded was wrong with psychiatric practices and institutions. I cheered Jack Nichols in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Alan Bates in King of Hearts, films that satirized the psychiatric world view. The inner pig also sounded suspiciously like the Baptist’s Satan.

Garnering attention and status in the group was achieved by confessing your sins of oppression and telling compelling stories of your own suffering. Being gay got you points. My shining moment came unexpectedly when I mentioned spending part of my boyhood living in a basement. That garnered underclass status points, which counted in those days. I’d never thought of the basement as that bad. It was the lower level of a structure that my parents were gradually turning into a split-level home. It had windows and doors and was surrounded by a forest where I spent much of my time. But I took the points.

MY GIRLFRIEND at the time also educated me in patriarchy’s evils. Ours was a mismatch. She was ten years older, and over time it became clear that what I most desired—she was beautiful, I was twenty-two—was not a shared relationship goal. She subscribed to a radical feminist journal called Quest, where I read an article proposing a utopia with no men and female reproduction handled by laboratories.

Though left-wing movements were run on fuming by the mid-70s, my fellow radicals convinced themselves that revolution was around the corner. There was no shortage of theories on how to start an American prairie fire, debated in endless meetings of the numerous sects. A favorite fantasy joke was that the Claremont Hotel, with its steam baths and tennis courts, would become the East Bay’s revolutionary headquarters. But having grown up on the prairie, I felt pretty sure the kids from my high school weren’t grabbing their pitchforks.

Mainstream feminism was on the rise, even on the prairie, and I celebrated it then and now. The Women’s Conference in Houston in 1977 was a watershed moment. My mother attended and later started a women’s shelter in Kansas. Among other things, I credit the women’s movement with enabling us to honestly discuss important things about her life for the first time. But among Berkeley’s radical feminists, more extreme positions—no men at all!—often garnered more attention and their advocates greater status.

In my men’s group, there were always one or two on the lookout for “mistakes”—saying the wrong thing, eating the wrong food, liking the wrong movie—and keen to correct us. A forerunner of political correctness and cancellation, its tweety evil twin, Radical Therapy’s path to social change began with personal purification. It was a finishing school that I flunked because ultimately I gave up on slaying my inner pig. I decided it wasn’t really a thing.

See also:

Violence on the Left, a personal story.

WHAT’S BARBARA THINKING?

Words we love… and hate

By Barbara Ramsey

MY UNCLE ED was driving my mother and me along an Alabama country road near her home when she pointed out what looked like a large puddle to our right. “Mr. Grimes sure can catch some good catfish in that pond,” she declared.

“What?” I was incredulous. “That can’t be more than three inches deep!” I looked over at Uncle Ed, an experienced Southern fisherman who could occasionally reason with his sister.

He paused, and then spoke in a low drawl, “Well, if there are catfish in that pond, they sure must have to hunker down.”

End of argument. Uncle Ed was a country lawyer with a great gift for language. “Hunker down” settled it.

When words like “hunker” come out of nowhere, they thrill me. I’m also fascinated by words with a close resemblance that people confuse and misuse.

Take disinterested and uninterested. Disinterested means “not biased” or “without selfish motive”. Uninterested simply means “not interested.” Many use them interchangeably to mean “not interested”. British writer Anthony Burgess labeled this “one of the worst of all American solecisms—it makes me boil.” Note the phrase “one of the worst.” Mr. Burgess had other bones to pick—bones that lie on the battlefield where Brits and Americans fight over words, spelling, pronunciation, and football vs. soccer.

But sometimes the enemy is us. My sister Pat is infuriated by people confusing enormous and enormity. Enormous is an adjective meaning very large. Enormity is a noun meaning “an act of extreme evil” as in “Hitler’s enormities shocked the world”. Over time, enormity has acquired a less pejorative connotation and can be simply “an act of very great size or importance.” Such word drift is a small matter to some people but to my sister it is an enormity.

Some word pair bewilderments bewilder me. I’ve never had trouble with the adverse and averse adjectives. Adverse means bad. Averse means to be ill-disposed to. A single “D” explains my adverse reaction to that guy I’m averse to.

Likewise insure and ensure, where there’s not so much as a “D” to help us out. Despite their similarity, insure and ensure seem quite distinct. Insure: to protect against a negative outcome. Ensure: to make certain. Quite separate in my mind.

Speaking of confusion, I was raised in a place where the soft “i” and soft “e” were pronounced almost identically. I say the words “pen” and “pin” the same way. They aren’t confused in my mind, but I have asked for a writing implement and received an object that pricked my finger.

One word pair that often throws me is affect and effect. In speech, the difference in voicing those initial vowels can be so subtle as to be non-existent, so I can use the wrong one and sound like I’m using the right one. But in writing? I am often perplexed. According to the dictionary, affect is a verb that means to impact in some way, whether that impact is negative or positive. Effect is also a verb but means to get a specific thing done and implies intention.

For example, “U.S. foreign policy almost always affects things in the world but rarely effects those things it desires.” If only I could memorize this example and make it stick! What’s worse is that affect and effect can both be nouns as well as verbs. Affect is usually a verb and effect is usually a noun, but this assumption is incorrect often enough to make me dizzy.

Possibly my favorite of these word pairs is confuse and conflate. I love that both words describe the awkward way they’re misused. Confuse means to mistake one thing for another. Conflate means to merge two things together, often in error. When a mix-up occurs, these separate meanings get conflated, which creates—you got it—confusion. Such an occurrence defines yet another word: irony.

FOR THE LOVE OF TYPE

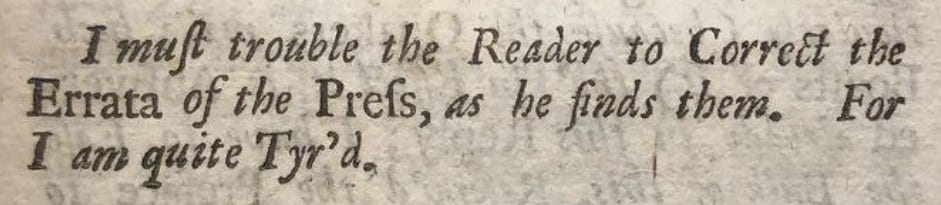

WILLIAM CASLON, the designer of this typeface, was born near the end of the 1600s. Caslon was the most popular typeface for English in the 1700s and is still in use today. (I’ve always been fond of it.) Benjamin Franklin purchased hundreds of pounds of the lead type from Caslon and it was the typeface used to print the Declaration of Independence. Errata (the plural of Erratum, a singular correction printed on a single page) were often published together at the end of a book. “Prefs” probably refers to the press that printed the book or handbill or poster—I can’t say exactly. After some effort tracking it down, I grew “Tyr’d” and gave up.

KUDOS and thanks to Tom Greensfelder who identified the artist behind the 18th century Comical Hotch Potch alphabet in last week’s edition of Wild Things. He is Richard Deighton. The publisher, Carrington Bowles, gave Deighton the “liberty to use contortions, perspective, and clothing to make legible letters.”

Snippets of the week

“I OFTEN PREFER pessimism. When things go badly, a pessimist can feel pleased with her prudence; when things go well, she can feel pleasantly surprised. Either way, she is content. But this pessimistic disposition is only healthy if she enjoys discovering that she was wrong, lest she develop a dogged longing for tragedy. Such pathological pessimism has the romantic allure of a Gothic poem.” —Megan Gafford

A WOODLAND PARK zoo employee was transporting Chilean flamingo eggs from Atlanta to Seattle when the incubator keeping the eggs warm malfunctioned. According to the Seattle Times, a flight attendant jumped into help, filling up rubber gloves with warm water to cover the eggs. Passengers added coats and scarves. The eggs successfully weathered the five-hour trip and later hatched four females and two males. Chilean flamingos are a near threatened species due to loss of habitat. Some of the birds I photographed five years ago were over forty years old and no longer breeding, so it’s hoped the young birds will boost the population there.

From Anne Schneider via email:

I do look forward to reading your writings. You make unusual topics of conversation extremely interesting and worthy of discussion. Barbara's treatise on words immediately reminded me of my father who drummed into us the importance of choosing correct and appropriate words. The conflation of empathetic and empathic was confusing, as was enthused and enthusiastic. He also emphasized the “correct” pronunciation of words. Pin or pen was his Apricot, long a or short a, argument. .

Kerry's pig story brought back my experiences at Berkeley, although from more than a decade before his, the beginnings of those conversations were there.

Please, carry on with your delightful musings.

Hi Kerry and Barbara - I’m Really enjoying Wild Things. I love the themes and stories and photos and contemplations. It’s fun, and heavy, and beautiful all at the same time - which is how I like things.